Rhetorical effect

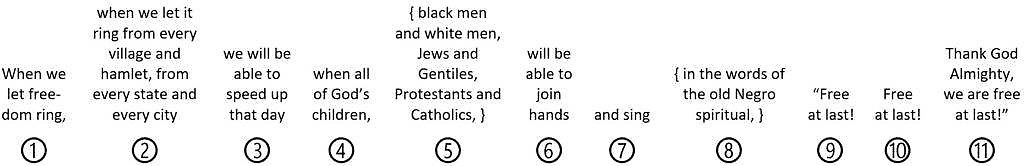

In the previous section, we saw how translating or interpreting a complex sentence based on a syntactic analysis of structure can disrupt the logical order in which information is presented. Another way a syntactic analysis can disrupt the flow of a text or speech is by weakening its rhetorical effect. To see how, consider the last sentence of Dr. Martin Luther King’s historic 1963 speech, “Freedom’s Ring,” known for its refrain‑like line, “I have a dream.” The sentence is shown in figure 56, grouped into functional propositions.

Last sentence of King speech – Original English

Each number in figure 56 corresponds to what would be a leaf on one of our semantic parse trees – a proposition or part of a split proposition. Numbers 5 and 8 are nested propositions, enclosed in brackets. Number 4 contains a syntactically isolated joint argument of the propositions whose predicates are in numbers 6 and 7. Number 8 is segmented as a separate proposition, because it contains information other than semantically typical information (see explanation in section 2.1 of annex I) and can be rephrased as a clause (“as the old Negro spiritual goes”).

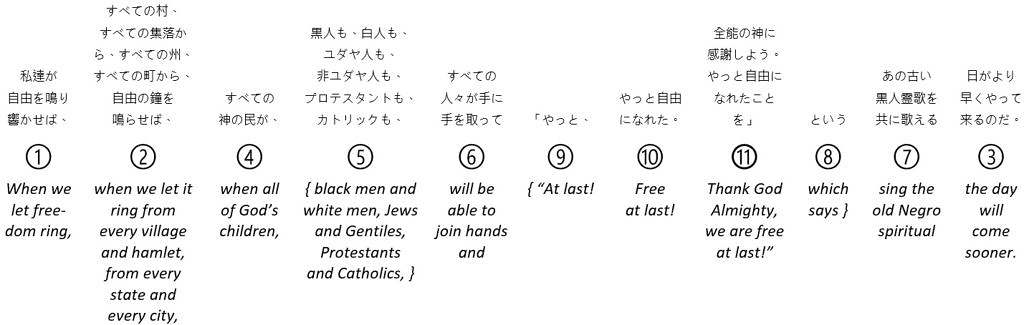

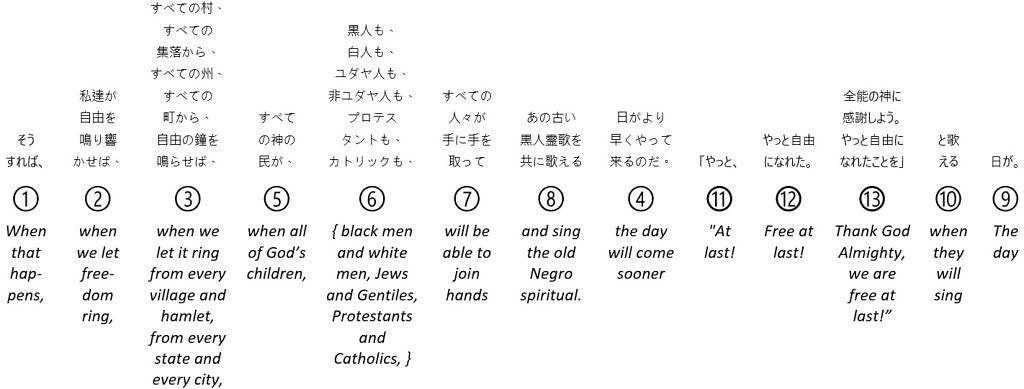

A hypothetical, structurally accurate Japanese version of the sentence in figure 56 is shown in figure 57. The numbers show the order the parts need to be read in to make sense in English.

Hypothetical, structurally accurate Japanese translation of sentence

There are several problems with the hypothetical, structurally accurate Japanese translation shown in figure 57. One problem is that it’s hard to process, because of the many nested propositions. And again there’s the problem of the logical order the events are described in. In the original English version, “we will speed up the day” comes before “when all of God’s children … will join hands and sing,” which is followed by the words of the song. This reflects the logical order of events hoped for: first the great day will come, then everyone will join hands and sing, then the words of the song will ring out.

This logical order is disrupted in the hypothetical, structurally accurate Japanese translation in figure 57, because of the difference in branching direction between English and Japanese. The Japanese translation first says everyone will join hands, then gives the words of the song, then says everyone will sing, and finally says the great day will come. The result may be confusing, since the events are described out of order. The relevant parts of the original English version and of the structurally accurate Japanese translation are compared in figures 58 and 59. The numbers there show the chronological order of the events in question.

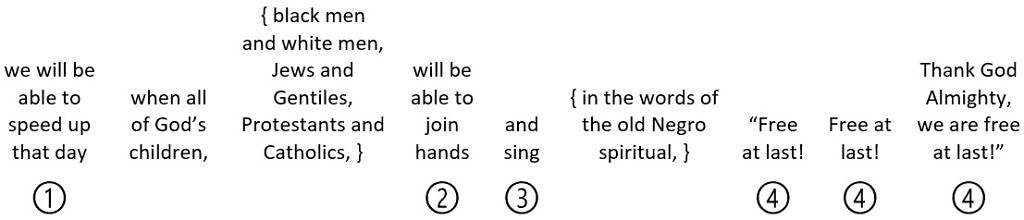

Figure 58

Original English version

Events described in chronological order

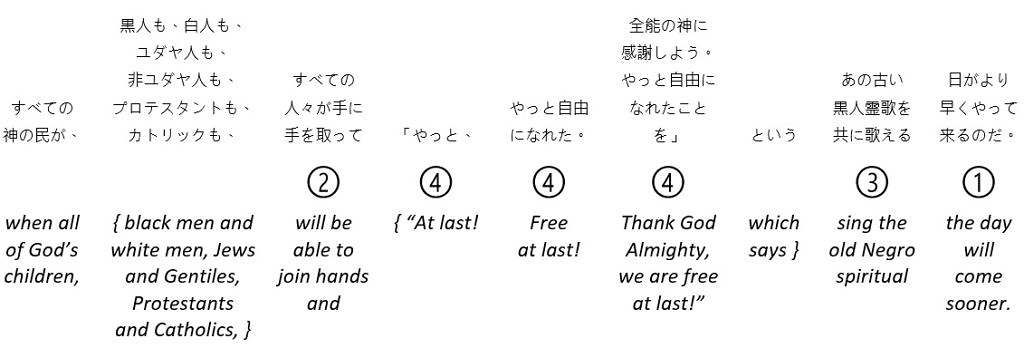

Figure 59

Hypothetical, structurally accurate Japanese translation

Events described in mixed-up order

But logical order isn’t the only problem. Another problem with the hypothetical, structurally accurate Japanese translation in figure 57 is the rhetorical effect of the order the events are described in. The original English version of the speech crescendos to the final words, “Free at last!” Those words are powerful for several reasons: the use of direct speech; their elliptical syntax; their repetition; their religious invocation; the sonorous way they’re declaimed; and the fact that they’re at the end of the speech, reverberating among the cheers of hundreds of thousands of people present at the event, and in the heads of listeners everywhere then and since. But this rhetorical effect may be diminished in the hypothetical, structurally accurate Japanese translation. Because complex sentence structure is head-final in Japanese, the structurally accurate Japanese translation places the inspiring words of the spiritual in the lowest level of a multiple nesting, followed by the last part of a syntactically split proposition, which is followed by a time description (“the day will come sooner”).

This illustrates another dilemma facing translators and interpreters working between languages with very different structure: the trade-off between ensuring structural accuracy, which can mean a lot of reordering, and preserving rhetorical effect, which can mean leaving information in its original order. Not only can changing the sequence of information in a sentence disrupt the logical order of events described. It can also weaken the rhetorical effect of describing events in a certain order.

A nice Japanese translation of Dr. King’s famous speech is published on the website MLK online. That translation, shown in figure 60, reflects the trade-off described above. Some structural accuracy is sacrificed, in exchange for greater ease of understanding, clearer logical order and more powerful rhetorical effect. This time the numbers indicate the order the phrases need to be read in to make sense in English.

Actual Japanese translation

The translator who produced the nice translation shown in figure 60 was apparently aware of the problems that would have been created by a structurally accurate translation. So they’ve chosen instead to move the words of the spiritual to a separate final sentence. One advantage of doing that is that it makes the first sentence easier to understand, creating fewer nestings than there would be in a structurally accurate translation. The other advantages are clearer logical order and greater rhetorical effect, as the inspiring words of the spiritual are now closer to the end of the speech. Given the various trade-offs described, the translator has taken a sound middle road, sacrificing some structural accuracy in exchange for improving other features of the translation.

As with any trade-off, the result isn’t perfect in every way. The event of the great day coming is still described after the event of everyone joining hands and singing. The words of the song still aren’t at the very end of the speech. And the main clause in the final sentence is elliptical, consisting only of the word “day” with a subject marker, to indicate what position that word – with all the propositions under it, including the words of the song – should be interpreted as having occupied in the previous sentence. Again, we see a number of trade-offs between structural accuracy and other features – ease of processing, logical order and rhetorical effect – in translating or interpreting complex sentences between languages with very different structure. As before, there’s no ideal solution.

Of course, translators or interpreters working in language pairs with very different structure aren’t always beset by such problems. If the sentences in the original text or speech are short and simple, structural issues like the ones described in this epilogue are less likely to arise. Even with longer, complex sentences, it’s sometimes possible to reorder propositions in translation or interpretation without creating a result that’s more confusing or less compelling than the original.

But where the original sentences are long and complex and involve successive event descriptions, lines of reasoning or passionate rhetoric, translating or interpreting complex sentences between languages with very different structure can produce a result that’s less than ideal – by splitting propositions, disrupting logical order, weakening rhetorical effect, or (in interpretation) placing too great a burden on working memory.

This epilogue on other challenges for translating and interpreting complex sentences between languages with very different structure winds up this study. All that’s left is for me to wish colleagues success in facing these challenges, hoping that I’ve managed to help them in some way.