Logical order

Logical order in interpretation

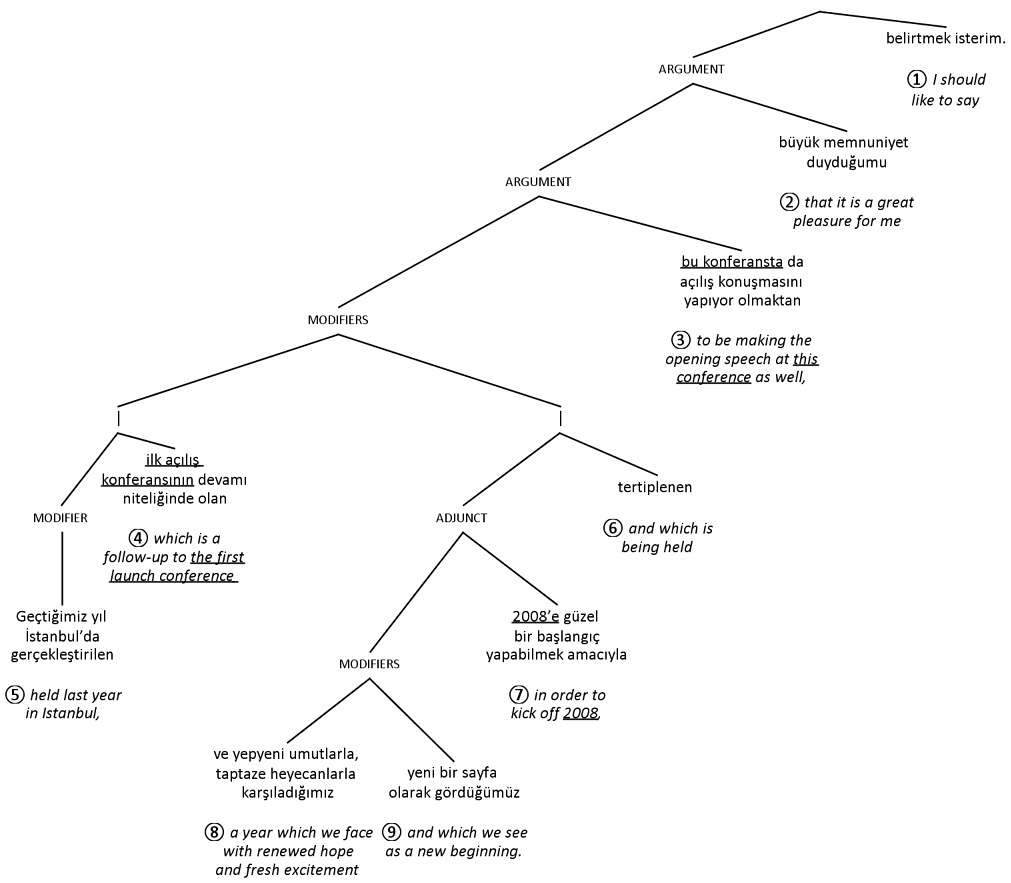

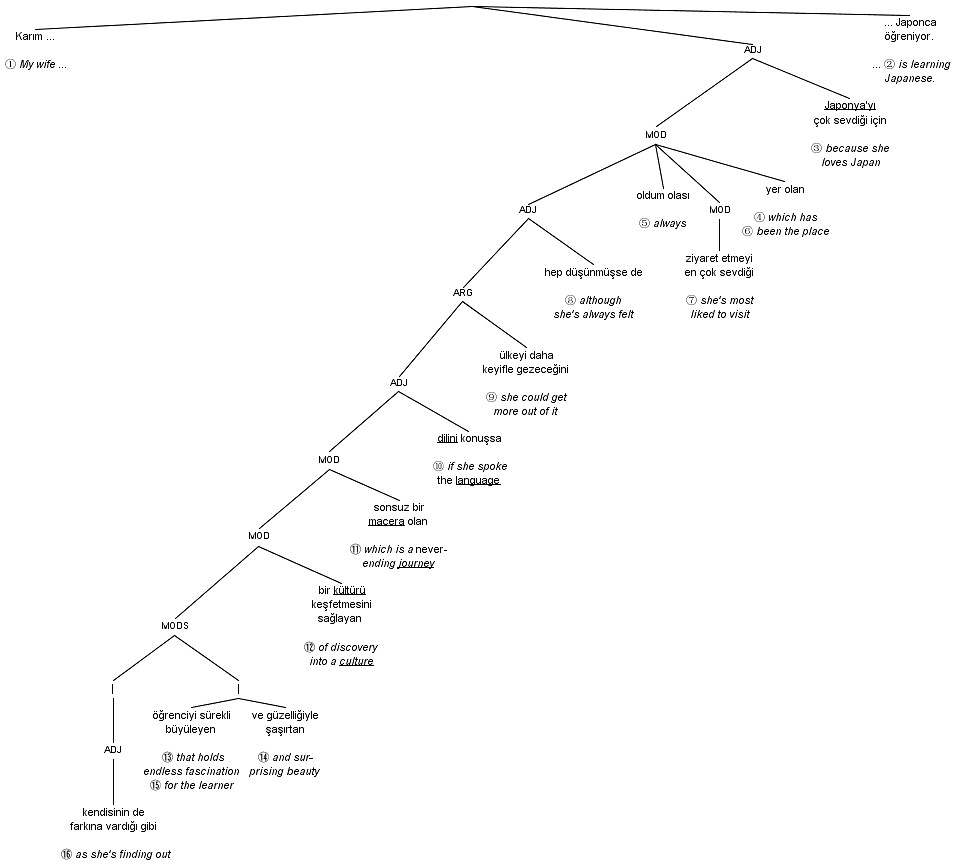

Translation or interpretation between languages with very different structure can involve disrupting the logical order of propositions as presented in the original message. For an example of this problem in simultaneous interpretation, let’s have another look at the long sentence from a Turkish speech shown at the end of section 5.2 on tactics for interpretation between languages with very different structure. The original Turkish sentence is reproduced in figure 50. The numbers again show the order the branches need to be read in to make sense in English.

Figure 50

Original Turkish sentence

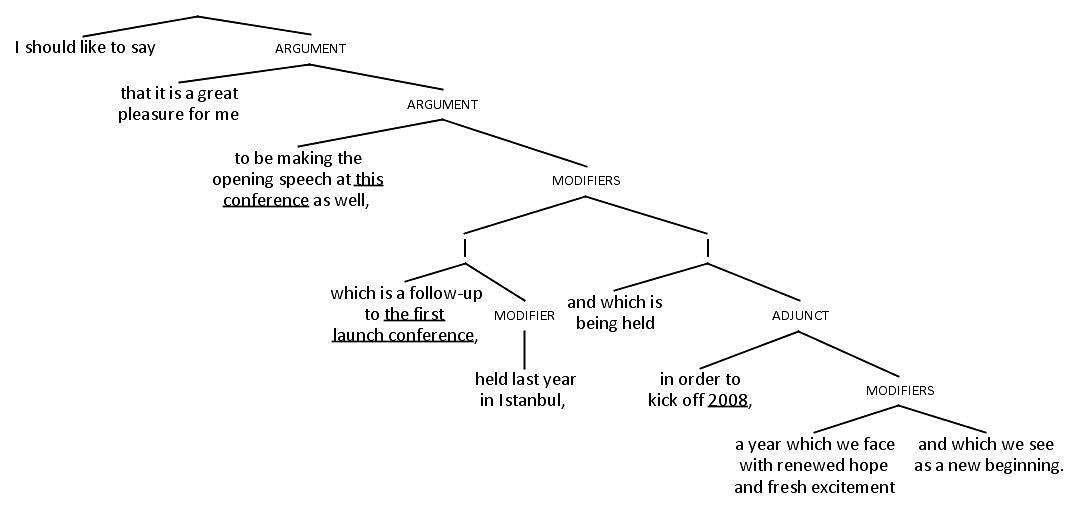

We also saw earlier a hypothetical, structurally accurate interpretation into English of the Turkish sentence shown in figure 50. That hypothetical English interpretation is reproduced in figure 51.

Hypothetical, structurally accurate English interpretation of sentence

We’ve already mentioned the difficulty of beginning to interpret such a sentence, because of the difficulty of anticipating where the speaker is going. And we’ve seen the problems that can arise through coping tactics like sentence division or syntactic restructuring. But there’s another problem with the hypothetical, structurally accurate English interpretation of the sentence shown in figure 51. That problem has to do with the logical order in which events are described.

In the original Turkish version of the sentence, the description “held last year in Istanbul” comes before “to be making the opening speech at this conference as well.” So the linear sequence of event descriptions in the original Turkish version reflects the chronological order of the events described. Likewise, “to be making the opening speech at this conference as well” comes before “that it is a great pleasure for me,” which comes before “I should like to say.” Here again, linear sequence reflects chronological order. First the speaker got the chance to speak, that made him happy, and now he’s telling us about it.

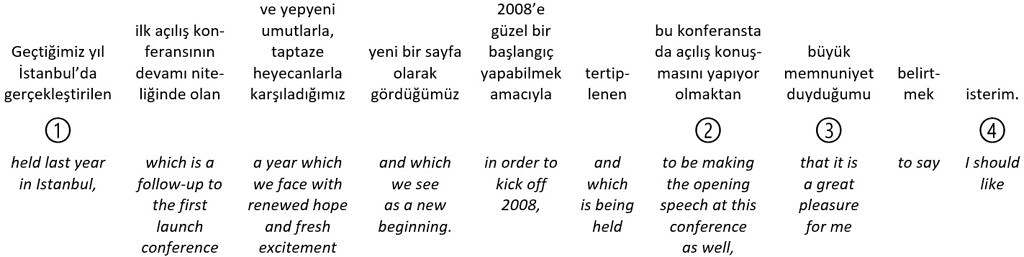

But an audience listening to a structurally accurate English interpretation of the same sentence, like the one in figure 51, would hear first about this year’s conference, then about last year’s. And they’d hear first that the speaker wants to say something now, then that what he wants to talk about is a feeling he’s had for a while, and finally what made him feel that way. Figure 52 shows the original Turkish version of the sentence, with numbers indicating the chronological order of the events in question.

Turkish original

Events described in chronological order

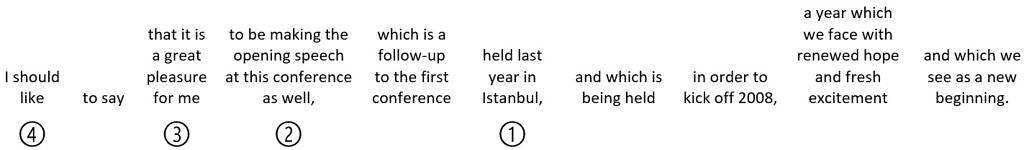

Figure 53 shows the hypothetical, structurally accurate English interpretation of the sentence. Again, the numbers show the chronological order of the events in question.

Structurally accurate English interpretation

Events described in reverse chronological order

Because of the structural difference between Turkish and European languages, this mismatch between syntactic sequence and chronological order of events is inevitable if the relations among propositions are accurately retained in interpretation. If the person giving the original speech had been speaking a European language, they might have produced a sentence describing the events in a sequence closer to their chronological order than the hypothetical English interpretation in figure 53. They might have started by saying, “After speaking at last year’s successful conference, …” We can only speculate. The point is that translating or interpretating complex sentences between languages with very different structure can involve yet another trade-off – between the structural accuracy of a sentence and the logical order of the events it describes.

In interpretation into a European language of a sentence like the Turkish one in figure 50, describing the events in clear, chronological order might be considered more important than preserving the hierarchical relations between propositions. The choice between these options can often be less than obvious, and the output can accordingly be easier or harder to follow.

Logical order in translation

Preserving logical order can be hard in simultaneous interpretation, because of the constraint on working memory. The task can be easier in written translation, as long as the translator is aware of the problem. To see how, let’s consider (22), a hypothetical run-on sentence about a speaker’s wife learning Japanese. (The same sentence is also given as an example in section 3 of annex I.)

(22) My wife’s learning Japanese, because she loves Japan, which has always been her favorite place to visit, although she’s always felt she could get more out of it if she spoke the language, which, as she’s finding out, is a never-ending journey of discovery into a culture that holds endless fascination and startling beauty for the learner.

Figure 54 shows a parse tree with a hypothetical Turkish translation of the sentence in (22) based on a syntactic rather than a semantic analysis of structure. The numbers show the order the branches need to be read in to make sense in English.

Turkish translation of complex sentence based on syntactic analysis of structure

There are a couple of problems with the hypothetical Turkish translation shown in figure 54. One problem is the long gap in the main clause at the top of the tree. Another problem is the potential weakening of assertive force in the subordinate clauses through grammatical deranking and syntactic nesting. (These two problems are discussed in section 3 of annex I.) A third problem with this translation is the difficulty of understanding information in the order it’s presented in.

Translating a complex sentence from a language like English into a language like Turkish based on a syntactic analysis of structure can result in an output sentence where the assertions are not only weakened through grammatical deranking and nesting, but also appear in reverse or mixed-up order. The original English sentence in (22) includes several assertions. Those assertions are made in the order shown in (23).

(23) My wife’s learning Japanese.

She loves Japan.

Japan’s always been her favorite place to visit.

She’s always felt she could get more out of it if she spoke the language.

She’s finding out what I’m about to say.

Learning Japanese is a never-ending journey of discovery into a culture.

That culture holds endless fascination for the learner.

It also startles the learner with its beauty.

Each sentence in (23) can be seen as an assertion, with its own place in an overall sequentially formed message. Mixing up the order the assertions are presented in can distort the logical coherence of that message. The hypothetical translation in figure 54 presents the assertions in a confusing order. That order is shown in (24).

(24) My wife’s involved in something [we’ll find out what at the end of the main clause] …

She’s finding out what I’m about to say.

Something holds endless fascination for the learner.

That thing also startles the learner with its beauty.

That thing is a culture and something else is a never-ending journey of discovery into it.

She’s always felt she could get more out of it if she spoke the language.

Japan’s always been her favorite place to visit.

She loves Japan.

… The thing my wife’s involved in is that she’s learning Japanese.

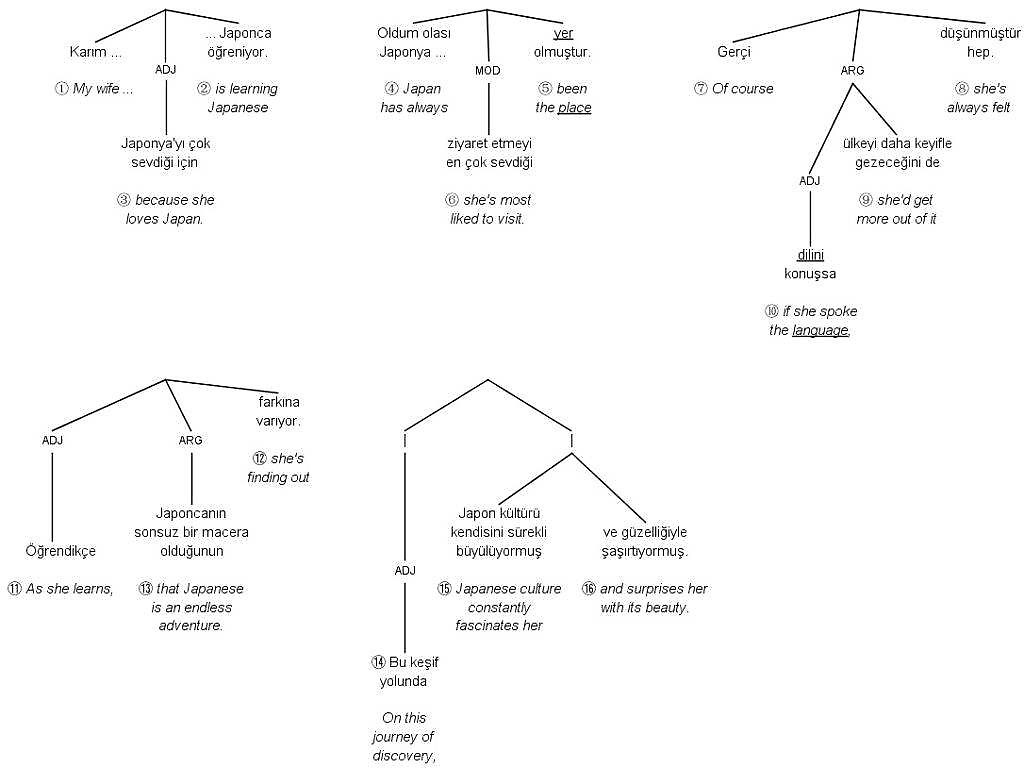

In a good translation based on a semantic analysis of structure, a complex sentence with multiple assertions in a European language can be rendered in a language like Turkish as a series of shorter sentences. Each of those shorter sentences can contain one functionally independent proposition corresponding to the main clause, and one or two other functionally independent propositions corresponding to subordinate clauses. An example, produced by expert translator and interpreter Aksel Vannus, is shown in figure 55. The numbers show the order the branches need to be read in to make sense in English.

Figure 55

Turkish translation of complex sentence based on semantic approach

A nice Turkish translation like the one in figure 55 sounds more natural and is much easier to understand than the one in figure 54 based on a syntactic analysis of the original sentence. One reason is that the nice translation doesn’t contain any long-distance attachments and doesn’t make the listener or reader wait for verbs. Research by Ueno and Polinsky (2009) shows that languages like Japanese and Turkish prefer structures that provide early access to the verb, even though the syntax of those languages requires a verb to be placed at the end of its clause. The other reason the nice translation sounds better than a syntactically accurate one is that the assertive force of the functionally independent propositions is maintained and moves forward from one assertion to the next, in the same order as in the original.

This section has shown how translating or interpreting complex sentences between languages with very different structure based on a syntactic analysis of structure can disrupt the logical order of a sentence. The next subsection discusses another way a syntactic approach can disrupt the flow of a text or speech.