3.3.1 Structural difference between languages

3.3.1.1 Branching direction

A major structural feature of any language is typical branching direction: whether a subordinate constituent tends to be placed before the constituent which subordinates it – in a “left-branching” structure – or after it – in a “right-branching” structure (Berg 2009). Most European languages have largely right-branching phrase structure. That also means that phrases in such languages are largely “head-initial.” That is, for most phrase types, the head of a phrase (like the main noun in a noun phrase or the main verb in a verb phrase) is typically at the beginning of the phrase. Chomsky and Lasnik (1993) include head directionality among the binary parameters of a language, set in the first stages of native language acquisition.

In this study, “structural difference” refers specifically to difference in the branching direction of subordinate clauses: whether the typical position of a subordinate clause in a given language is before or after its parent clause.

A left‑branching structure in English, with the subordinate clause preceding its parent, is shown in (3).

(3) Before you leave the room, please make sure to switch off all the lights.

A right-branching structure, with the subordinate clause following its parent, is shown in (4).

(4) Please make sure to switch off all the lights before you leave the room.

The typical branching direction of subordinate clauses varies by language and type of clause.

Let’s start by comparing English and Mandarin. One issue for translating or interpreting complex sentences in a language pair like this is the typical branching direction of a relative clause, as in (5).

(5) Marie is the woman I’ve always dreamed of.

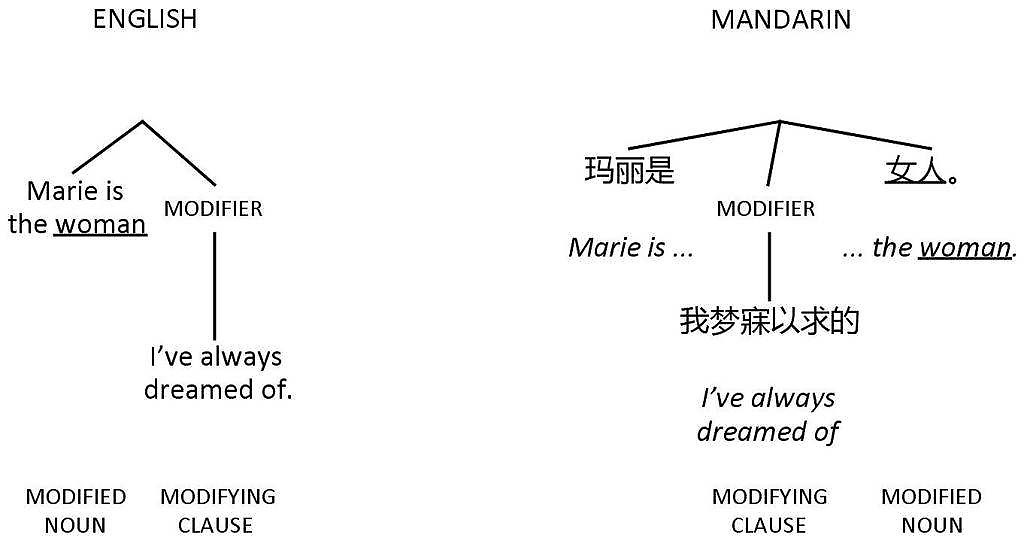

A relative clause typically appears after the noun it modifies in a European language, whereas it typically appears before the modified noun in a Sinitic language, as illustrated in figure 5.

Figure 5

Typical placement of a relative clause in English and Mandarin

The English structure in figure 5 is right-branching, with the modifying clause coming after the modified noun in the parent clause. In the Mandarin version, the modifying clause syntactically splits the parent clause, coming before the modified noun, in a left-branching structure.

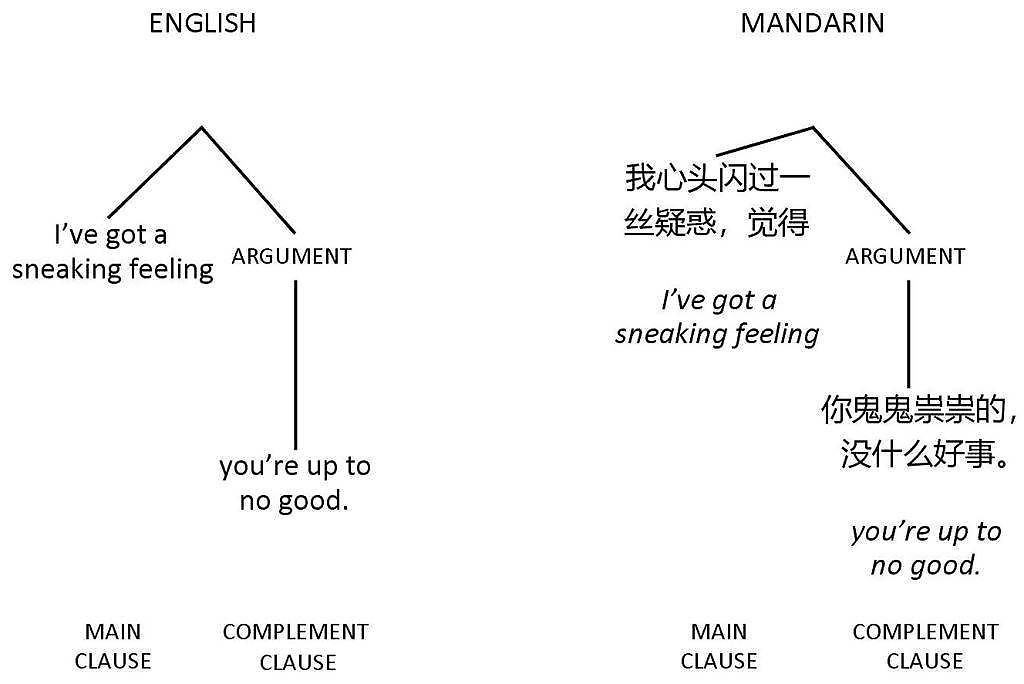

Another type of subordinate clause is a “complement clause.” This is a clause that functions as an argument (subject or complement) of the predicate in its parent clause, as in (6).

(6) I’ve got a sneaking feeling you’re up to no good.

In a Sinitic language, just as in a European language, a complement clause typically follows its parent clause in a right-branching structure, as illustrated in figure 6.

Figure 6

Typical placement of a complement clause in English and Mandarin

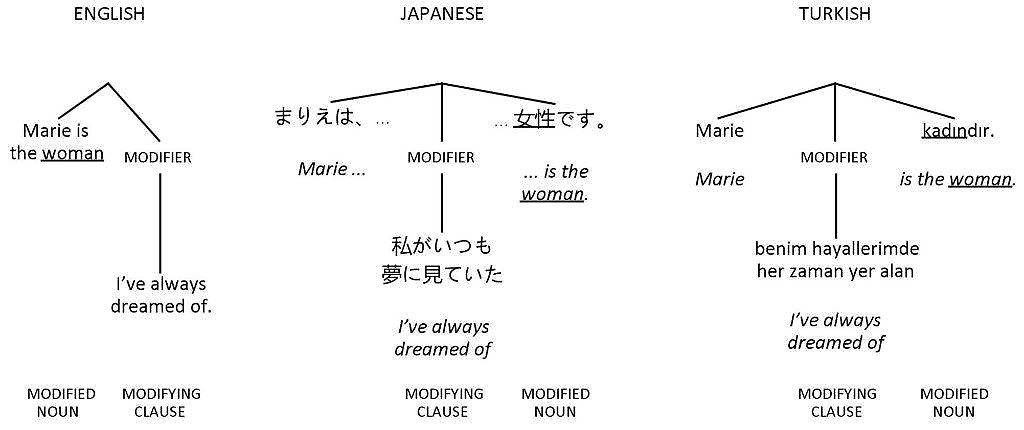

Some languages are even more structurally different from English than Mandarin. In a language like Japanese, Korean or Turkish, complex sentence structure is consistently left-branching. So a relative clause in one of those languages typically goes before the noun it modifies in the parent clause, as illustrated in figure 7.

Figure 7

Typical placement of a relative clause in English, Japanese and Turkish

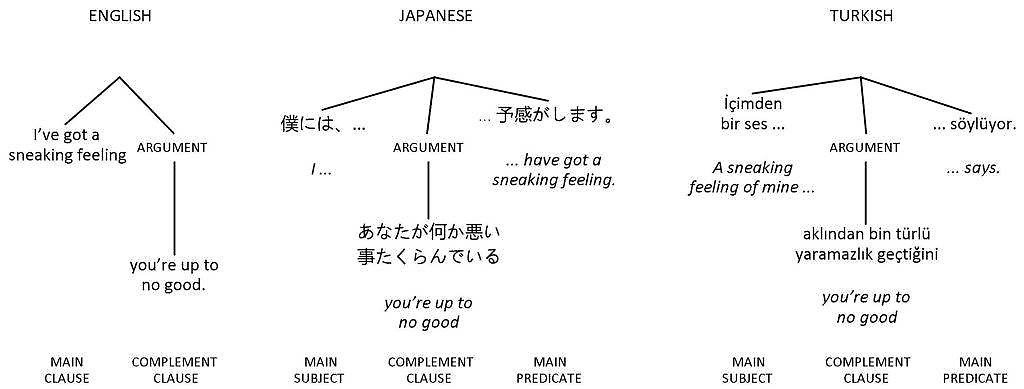

A complement clause in a language like Japanese, Korean or Turkish typically goes before the predicate in the parent clause, often syntactically splitting that clause, as illustrated in figure 8.

Figure 8

Typical placement of a complement clause in English, Japanese and Turkish

3.3.1.2 Branching direction typology

Languages are generally held to have three major types of subordinate clause: relative clauses, which act largely like adjectives; complement clauses, which act largely like nouns; and adverbial clauses, which act largely like adverbs (Quirk et al. 1989: 1047). Language typologies in terms of the typical branching direction of these three types of subordinate clause are given by Diessel (2001), Dryer (2007; 2013) and Schmidtke-Bode and Diessel (2017). These typologies are the basis for classifying the six languages in this study in terms of their complex sentence structure.

According to the typologies mentioned, a relative clause or a complement clause is typically placed after its parent in every Indo-European language, regardless of the position of a verb within its clause. Some linguists classify Hungarian and Finnish as typically right-branching and others as typically left-branching (Kiss 2002: 6). In those languages, a left‑branching relative clause can occur in formal register. Otherwise, both a relative clause and a complement clause typically follow their parents, as in Indo-European languages. Sino-Tibetan languages like Mandarin are more mixed in complex sentence structure, with a relative clause typically coming before the noun it modifies and a complement clause coming after its parent.

In contrast, languages like Japanese, Korean and Turkish are typically left-branching, with any type of subordinate clause preceding its parent. The typical position of a main verb in such languages is at the end of a sentence, no matter how complex that sentence may be. Nor is there mixed phrase structure, including some typically right-branching phrase types. The result, compared to Indo-European languages, is an inverse order of constituents in most phrase types – except for clauses, where the subject is typically near the beginning – plus, crucially, a largely inverse order of clauses in a complex sentence.

Following the typological classifications cited above, Table 1 shows the typical branching direction of the three major types of subordinate clause, in the six languages considered in this study.

Table 1

Typical branching direction of subordinate clauses

| Language | Relative clause | Complement clause | Adverbial clause |

| English | right | right | either |

| Russian | right | right | either |

| Hungarian | either | right | either |

| Turkish | left | left | left |

| Mandarin | left | right | left |

| Japanese | left | left | left |

The second and fourth columns of table 1 show that, for all six languages considered, the typical branching direction of adverbial clauses can be uniquely predicted based on the typical branching direction of relative clauses. If one of the languages in question has relative clauses that typically branch to the right or either way, it will have adverbial clauses that typically branch either way. And if one of those languages has relative clauses that typically branch to the left, it will have adverbial clauses that also typically branch to the left. So, to avoid redundant data, our statistical analysis only considers the typical branching direction of relative clauses and complement clauses in each language pair.

For each language of translation or interpretation in our study, these two variables for branching direction are combined into a single variable for structural difference from English. That variable has four possible values: same (relative and complement clauses which both typically branch to the right, as in Russian); somewhat different (relative clauses which typically branch either way and complement clauses which typically branch to the right, as in Hungarian); moderately different (relative clauses which typically branch to the left and complement clauses which typically branch to the right, as in Mandarin); or opposite (relative and complement clauses which both typically branch to the left, as in Turkish and Japanese). That combined variable for structural difference is one of the three independent variables recorded for each sentence in our corpus and analyzed. The other two independent variables recorded for each sentence are: mode of language transfer (legal translation, subtitle translation or simultaneous interpretation) and sentence complexity (as measured by the number of subordinate propositions in the original English version of a sentence).

Now let’s have a look at the dependent variables recorded for each translated or interpreted version of each sentence in the corpus: the three features identified as indicators of difficulty in translation or interpretation.

← 3.3 Variables

→ 3.3.2 Reordering