3.3.3 Nesting changes

A “nesting” in this study means a structure where one proposition is syntactically surrounded by the predicate and any arguments of another proposition. The positions of adjuncts and propositional links (like subordinating conjunctions or complementizers) aren’t taken into account here, since they’re more loosely attached to a predicate than its arguments. A nesting in English is shown in (9).

(9) The cat the dog was chasing ran up the tree.

In (9), the subordinate proposition syntactically splits the predicate of its parent proposition (“ran”) from one of the arguments of that predicate (“the cat”). Creation or elimination of such nested structures is taken in this study as an indicator of difficulty. Here’s why:

Karlsson (2007) shows that multiple nested clauses are avoided cross-linguistically. This is evidence that a nested clause increases processing difficulty.

But a semantic proposition can take different syntactic forms. It can be expressed in an independent clause, as in (10).

(10) I love you.

Or it can be expressed in a phrase headed by an abstract noun, as in (11).

(11) My love for you is strong.

A proposition can be expressed in a complement clause, as in (12).

(12) You know that I love you.

Or it can be part of a clause headed by a subordinating conjunction, as in (13).

(13) I’m here because I love you.

A proposition can be expressed in a relative clause, as in (14).

(14) You’re the one I love.

Or it can be expressed in a gerund phrase, as in (15).

(15) Nothing can stop my/me loving you.

A proposition can also be part of a phrase with a preposition subordinating an abstract noun, as in (16).

(16) I’m here because of my love for you.

In languages with cases, it can also be part of a case phrase.

Given the variety of syntactic forms used to express propositions, it seems reasonable to assume that Karlsson’s evidence that nested clauses increase processing difficulty, cited above, can apply to nested syntactic expressions of semantic propositions in general, whatever their syntactic form. Moreover, studies by Hawkins (2014) and others reveal a cross-linguistic preference for minimal distances between a phrase head and its directly subordinate syntactic constituent. A nested proposition of any type increases the distance between the predicate of the parent proposition and one or more of its arguments, thereby increasing processing difficulty.

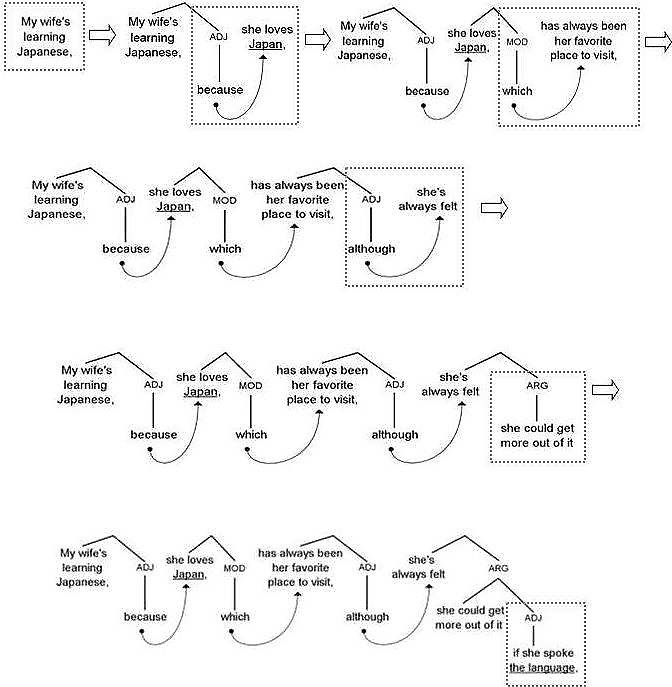

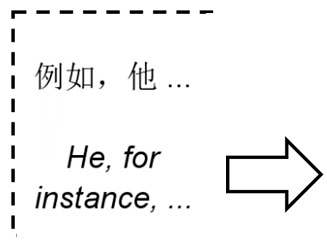

A sentence can be complex and still relatively easy to process. This is the case if the elements of each proposition are contiguous, keeping the phrasal combination domains small. In such a sentence, a succession of logical “windows,” each the size of a single proposition and a syntactic link, is enough to allow the listener or reader to process each link and proposition in turn, as illustrated in figure 10.

Dynamically unfolding semantic parse tree

with successive small logical processing windows

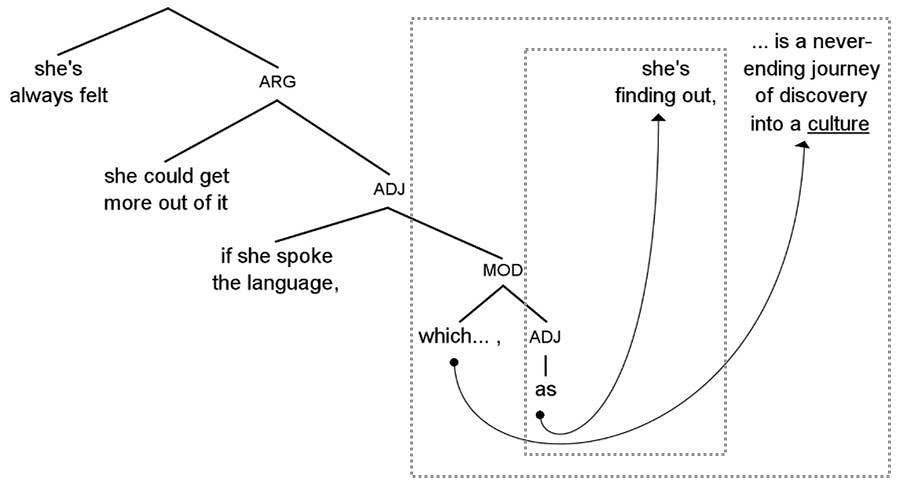

The problem for keeping just one small logical window open arises when one proposition interrupts another, as illustrated in figure 11.

One proposition interrupting another

In figure 11, the process of phrasal domain construction started by the argument “which” (referring to “the language”) can’t be completed till that argument finds its predicate, “journey.” In the meantime, the logical window for that proposition has to stay open and expand to include a second window onto the intervening proposition, “as she’s finding out.” In figure 11, that second window is small, so the first window can still be managed easily enough. But the more propositions intervene before the phrasal domain is constructed and the more complex they are, the larger a logical window like this has to become to accommodate accumulating information before it can be resolved and close.

In a language with typically left-branching structure, like Japanese or Turkish, a clause or other phrase expressing a proposition generally has its subject near the beginning and its predicate in final position. So a complex sentence in a language like that can have more nestings than a comparable sentence in a language with typically right-branching structure, like a European one. This tendency towards nesting in a left-branching language can be particularly strong in formal speech and even stronger in formal writing, where long, complex sentences can be common.

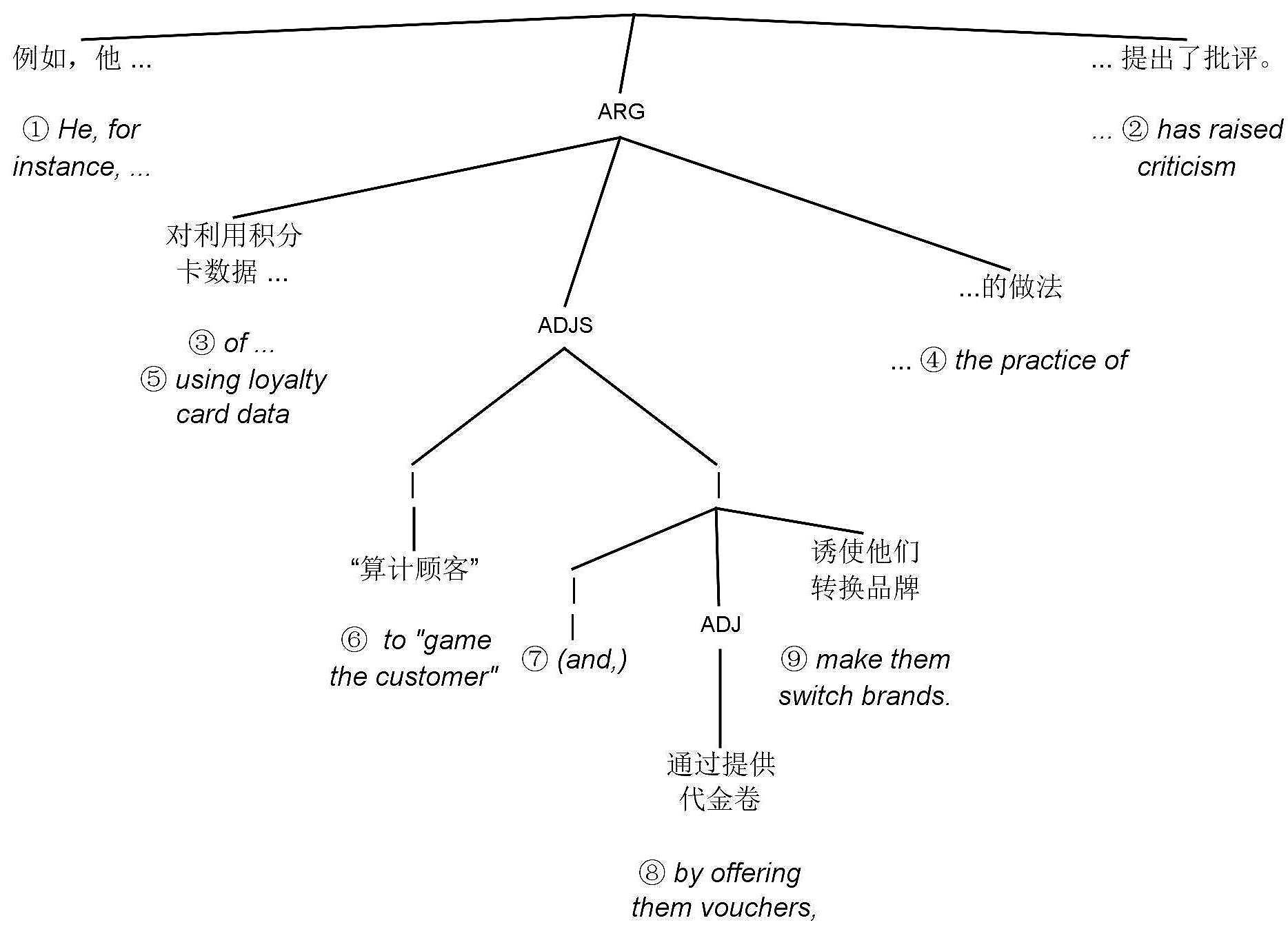

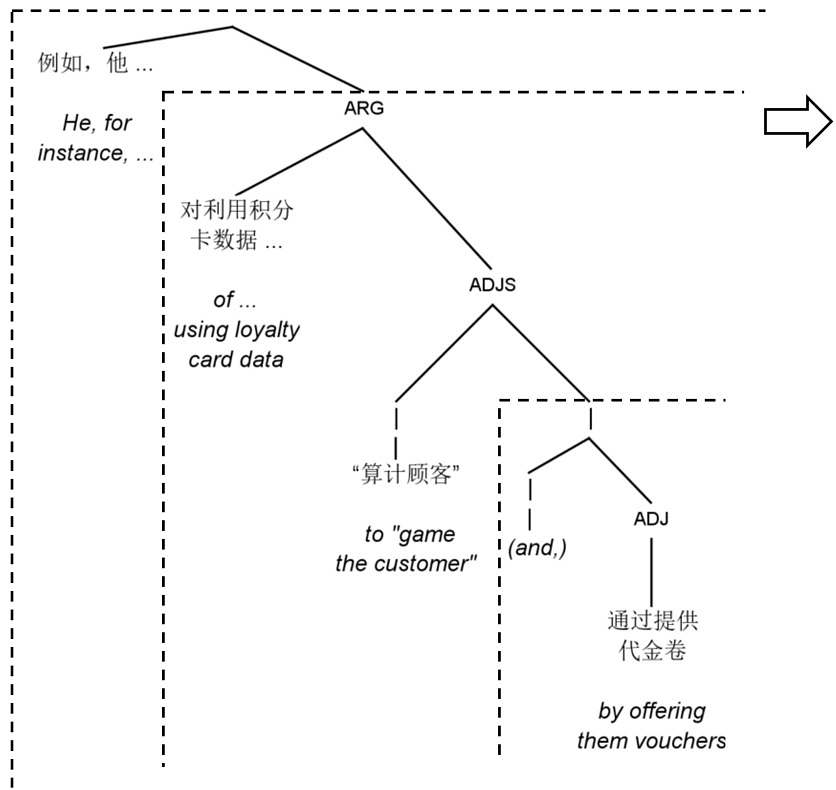

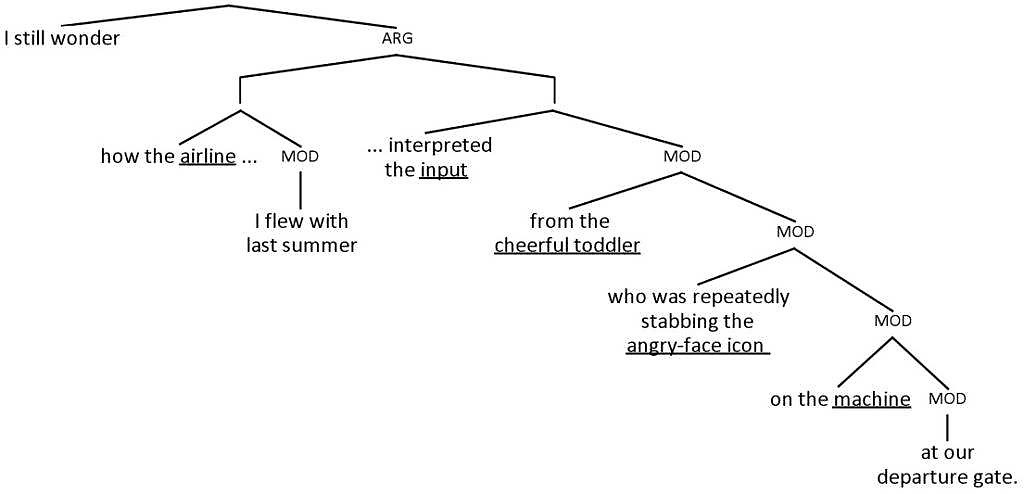

The higher nesting rate that can characterize formal writing in a left-branching language, or in a language with mixed branching structure, may be compounded in translation from a right-branching language. For example, figure 12 shows a parse tree of the propositions in an English sentence from a 2016 article by A. Hill in the Financial Times.

Original English version of sentence

As this sentence moves forward and logical windows open onto successive propositions, each proposition can be processed before or as soon as the next one begins. So each window can be kept small, as illustrated in figure 13.

Successive small logical processing windows

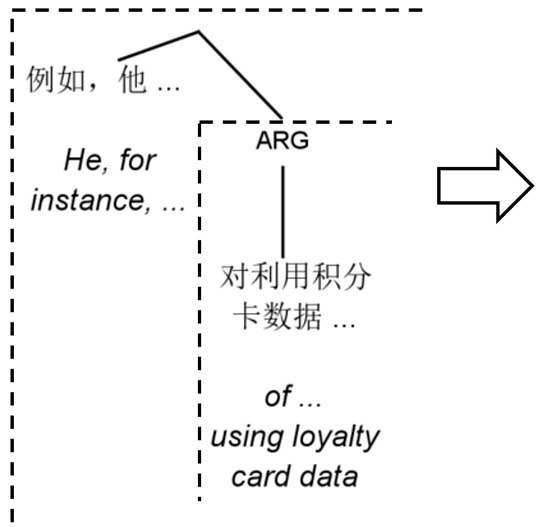

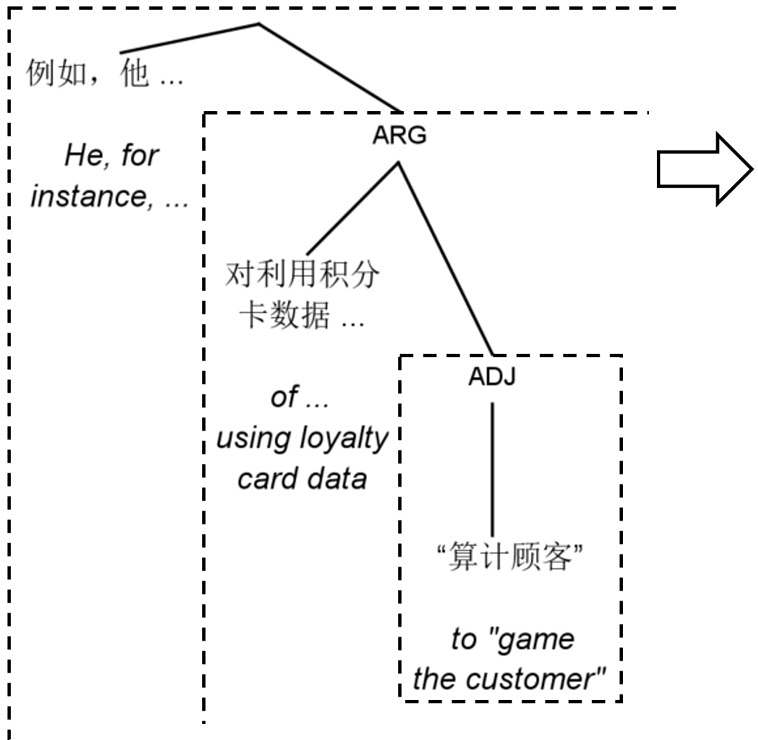

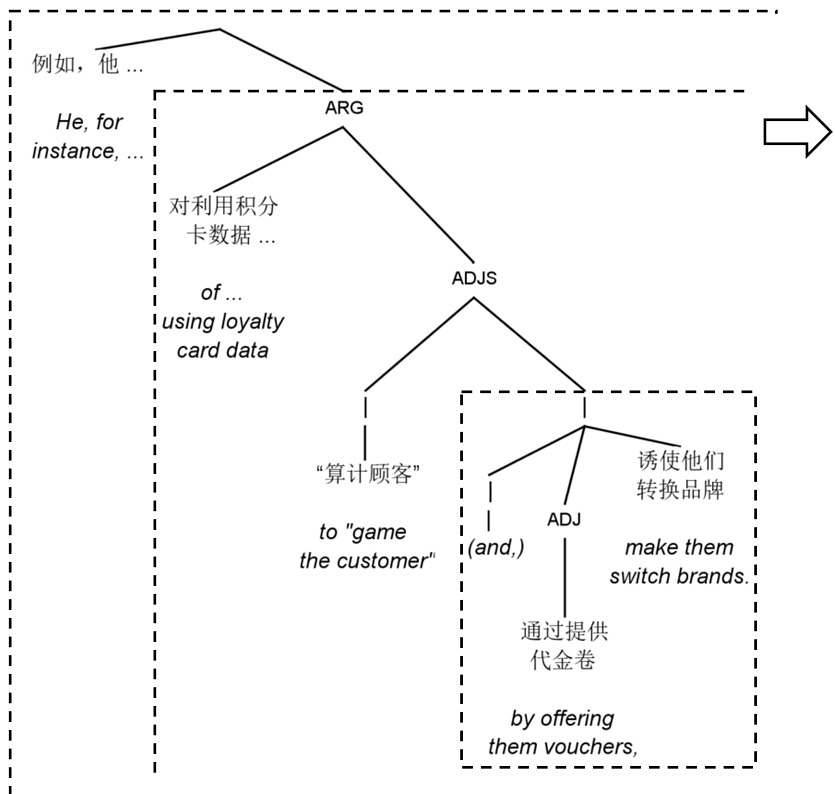

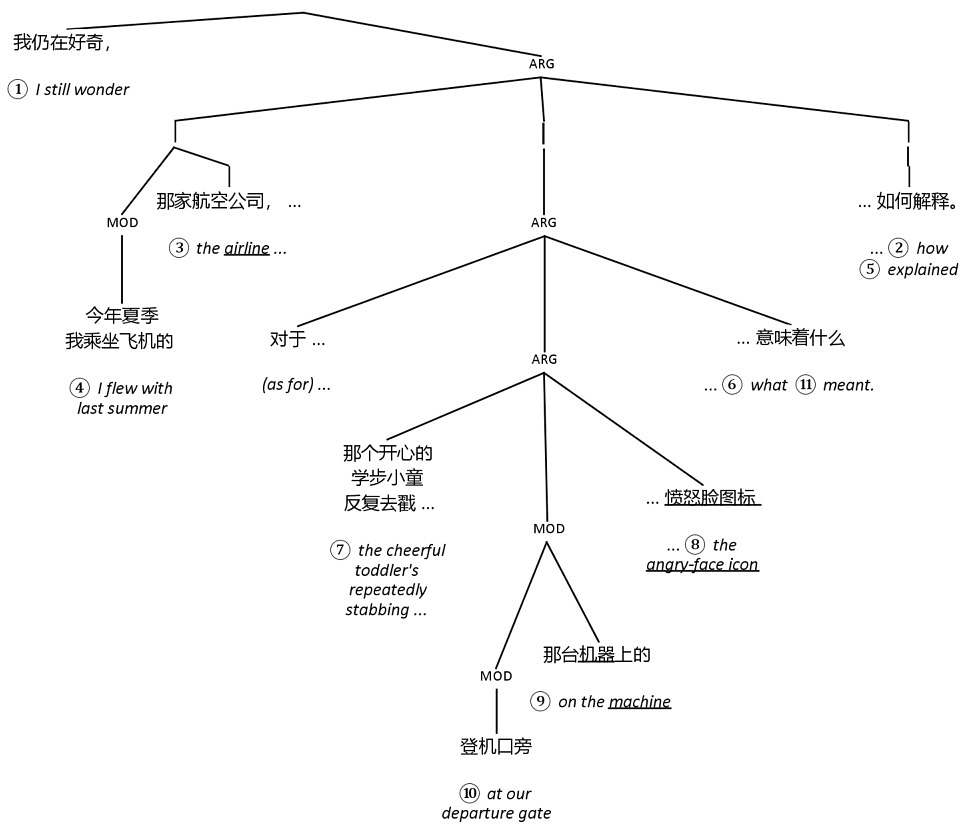

But the same sentence from the article as it appeared in Mandarin translation in the Financial Times Chinese has several syntactically split propositions, with parts which stay unresolved over long distances, as illustrated in figure 14. The numbers show the order the branches need to be read in to make sense in English.

Figure 14

Mandarin translation of sentence

In the mind of the reader of the Mandarin sentence in figure 14, several logical windows have to stay open and grow as the sentence moves forward. The window opened by the argument “he” at the beginning can’t close till it finds its predicate, “has raised,” at the end of the sentence. Meanwhile, that window has to stay open and grow to include a new logical window for processing the next proposition. That second window also has to stay open till the first part of the phrase “of … using” can attach to “the practice of” near the end of the sentence. This process is illustrated in figure 15.

without closing

without closing,

first window still growing

first and second windows still growing

first and second windows still growing

first and second windows still growing

first window still growing

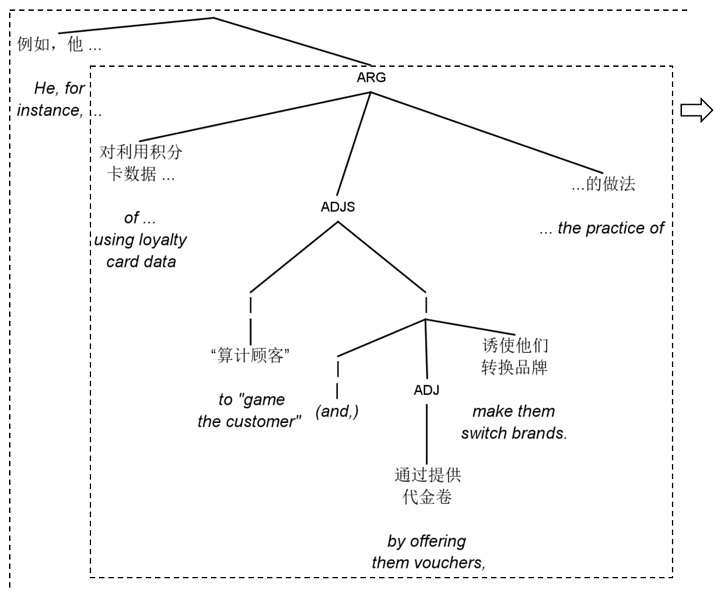

Figure 15

Large logical windows needed for processing multiple split propositions

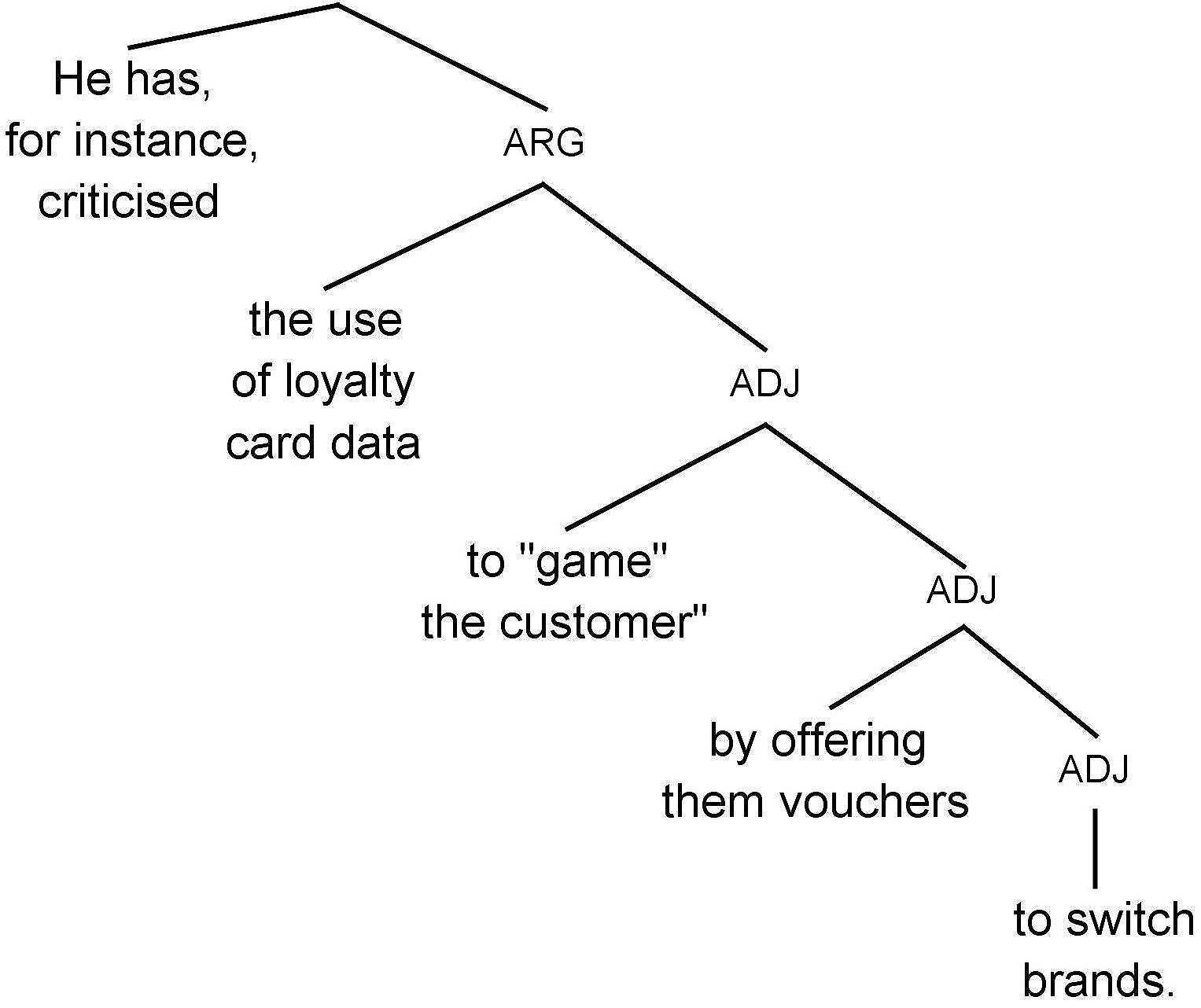

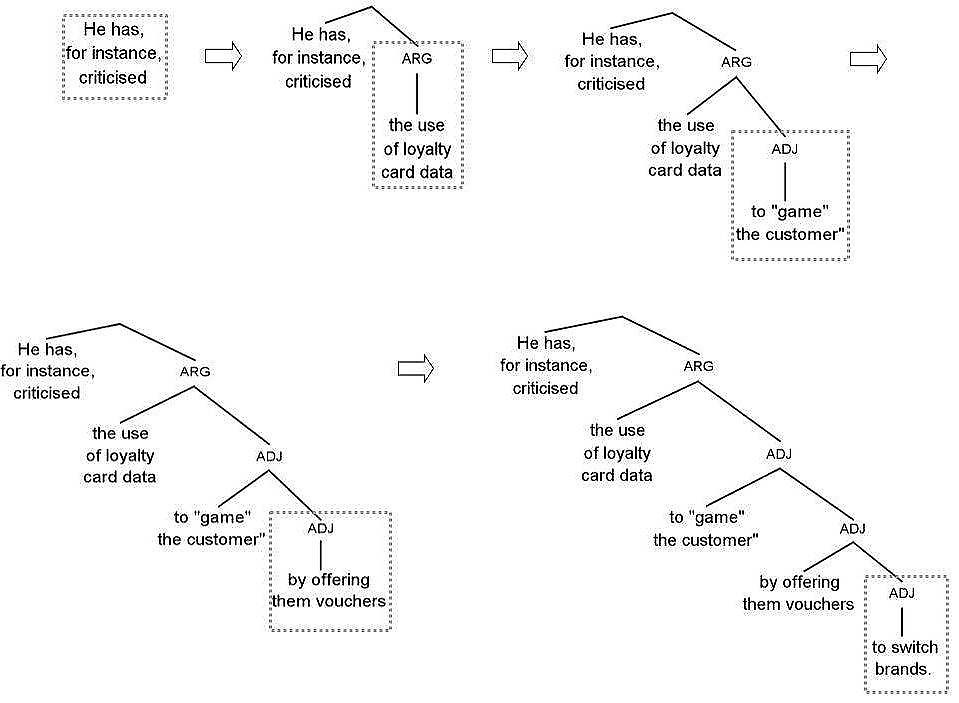

Figure 16 shows a parse tree of another sentence from the same article, with one syntactically split proposition in English.

Original English version of sentence

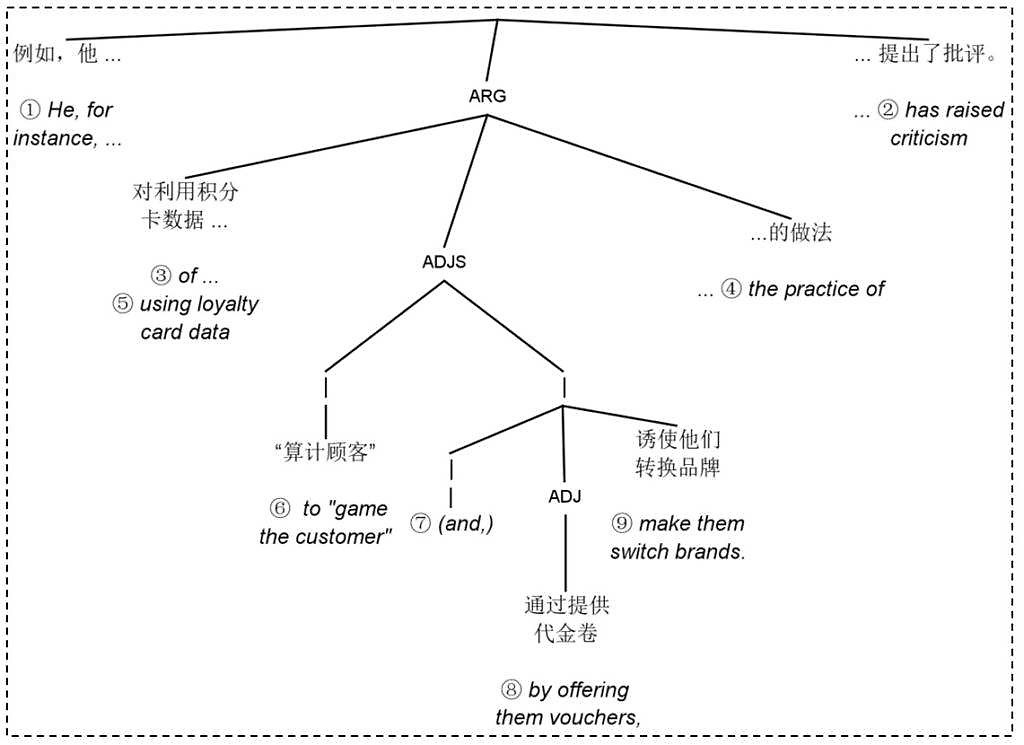

Figure 17 shows a parse tree of the Mandarin translation, with many split propositions and several layers of nesting. The numbers again show the order the branches need to be read in to make sense in English.

Figure 17

Mandarin translation of sentence

The original English versions of the sentences in figures 12 and 16 are both easy enough to process. But the Mandarin translations in figures 14 and 17, though structurally accurate, are much harder to process, because of the multiple nestings in each. Mandarin translations of foreign publications can be full of this sort of unwieldy structure. This may be because the translators are careful to preserve the structure of the original text. If they’re translating an official text, they may feel under even more pressure to be precise. And they – or their supervisors or editors – may be unaware of or unconcerned by the trade-off between structural accuracy and processing difficulty illustrated in these examples.

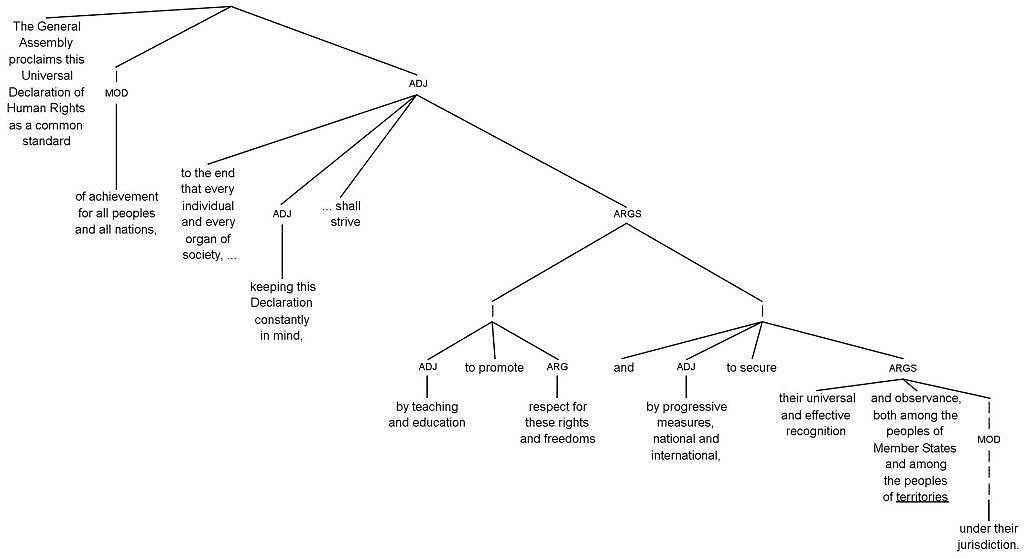

As we saw earlier, subordinate clauses in languages like Japanese and Turkish are typically left-branching. So translating a complex sentence from a right-branching European language into one of those languages can create even greater structural problems than translating into Mandarin, where the typical branching direction of subordinate clauses is mixed. For example, figure 18 shows a parse tree of the propositions in a sentence from the English version of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

English version of sentence

The English version of the sentence in figure 18 has only one short nesting and no long-distance dependencies. So it’s easy enough to process for the average reader, despite its length and complexity. Figure 19 shows a parse tree of the propositions in the Turkish translation of the same sentence. The numbers again show the order the branches need to be read in to make sense in English.

Figure 19

Turkish translation of sentence

In the Turkish translation shown in figure 19, one argument and the predicate of the main proposition are at the beginning and the end of the sentence, syntactically surrounding an enormous nested proposition. That proposition in turn surrounds three other nested propositions. One of those has two even more subordinate propositions. The other one has three, one of which is nested inside its parent.

Here the translator has opted for structural accuracy over processing ease. They may well have been influenced by the importance of the document and felt a need to reproduce its content faithfully. But the resulting message, which is supposed to be compelling and inspiring, may be nearly incomprehensible to the Turkish reader, because it’s so hard to process. This case of multiple nesting is extreme. But it’s very real nonetheless, characteristic of the type of language that can be found in translations of official texts. It illustrates the trade-off between structural accuracy and processing ease which can face translators and interpreters working between languages with very different structure.

As we’ve seen, the number and degree of nested propositions in a sentence is a factor of processing difficulty. But creating or eliminating a nested structure in translation or interpretation is a factor of production difficulty as well. If the original version of a sentence has a non-nested proposition and the corresponding proposition in translation or interpretation is placed in a nested structure, the transformation involves splitting the parent proposition. On the other hand, if the original version of a sentence has a nested proposition, the translator or interpreter may need or may choose to repackage the message in such a way that one proposition no longer splits the other. Eliminating a nesting in that way, like creating a nesting, is likely to involve extra mental effort, as both transformations involve reordering the predicate and arguments of the parent proposition.

In sum, creating or eliminating a nesting can be taken as an indicator of difficulty for the translator or interpreter. This is the second indicator of difficulty measured in this study.

← 3.3.2 Reordering

→ 3.3.4 Changes in semantic relations