3.3.4 Changes in semantic relations

A “semantic relation” in this study means the place and type of attachment of a functionally subordinate or reported proposition – in other words, which parent it’s directly attached to and its semantic role in relation to that parent. For example, consider (17).

(17) Answer the questions on the board.

Pragmatic knowledge suggests that the phrase “on the board” is meant to be taken as a modifier of the noun “questions.” But that phrase might instead be translated or interpreted into another language as an adjunct to the predicate “answer.” So the translated or interpreted sentence would end up with the meaning shown in (18).

(18) “Answer the questions (and write your answers) on the board.”

Similarly, consider (19).

(19) Please report any problems using the attached complaint form.

This English sentence might be translated or interpreted into another language as a request to report any problems involving use of the form. But pragmatic knowledge of what a complaint form is suggests that the request is in fact for the form to be used to report any problems that might arise.

A translated or interpreted version of a complex sentence which changes the hierarchical relations between propositions in the original version isn’t necessarily wrong. It just means that the propositions in question aren’t attached in the same ways in both versions of the sentence. The fact that a translator or interpreter made such a change suggests that they were somehow unable to reproduce or uncomfortable reproducing the original semantic relations.

Sometimes a change in semantic relations may be more or less deliberate. That is, the translator or interpreter may be aware that their version of a sentence doesn’t accurately reflect the hierarchical structure of the original. But they may sacrifice that accuracy for some other benefit – because they feel the change makes the result clearer, stronger or more natural. Other times such a change may be less intentional. It may reflect mistaken parsing – misconstruing the structure of the original message. Or it may result from mistaken formulation – failing to reproduce that structure appropriately in the other language. An interpreter may also make such a change because it eases the burden on their working memory.

Gile (2009) suggests that cognitive load in interpretation is shared among three efforts – listening, remembering and speaking. He observes that “it is difficult to assess the added cognitive load which can be attributed to each Effort at each time,” and that “processing capacity requirements for each individual Effort are probably determined not only by their individual needs, but also by their interaction” (p. 169). Whatever the reason or combination of reasons for a given change in semantic relations, the fact that such a change was made is taken here as an indication that the translator or interpreter encountered some sort of difficulty that led them to do so, rather than reproducing the hierarchical structure of the original.

Even in written translation, where there’s much less of a working memory or timing constraint, changes in semantic relations can be common in transferring complex sentences between languages with very different structure. And in simultaneous interpretation between such languages, some structural distortion may be practically unavoidable.

Of course, relations between parts of the original version of a sentence may be ambiguous or hard to understand in any language. But such ambiguity or unclarity can be masked in translation or interpretation between structurally similar languages, where it can often be copied directly from one language to the other. In translation or interpretation between languages with very different structure, such ambiguous or hard-to-understand relations can be more liable to lead to a mistake in parsing or formulation, potentially creating a major distortion of meaning.

Taking reordering and nesting changes as indicators of difficulty in translation or interpretation is justified empirically, as we’ve seen. The case for taking changes in semantic relations as an indicator of difficulty is more pragmatic. When a group of propositions attached in one way in the original version of a sentence is isolated and contrasted with the same propositions attached in a different way in translation or interpretation, it’s generally clear that the meaning is different in that respect.

When dealing with a short sentence, a good translator or interpreter would be unlikely to make such obvious mistakes as the ones described for (17) and (19). It should be clear from the situation at a test that people are supposed to write their answers on paper. Or it should be clear from general knowledge that a complaint form is to be used for reporting a problem. But in long, complex sentences like those characteristic of legal texts, especially if the translator or interpreter isn’t familiar with the details or the larger context, alternative readings of the relations between propositions can be common. And failure to reproduce those relations as originally intended can have major consequences. Translators and interpreters can make and fail to spot such mistakes when the sentence parts involved are obscured by other intervening and surrounding phrases – especially if those phrases are differently placed in the two language versions of a sentence. But when that extra verbiage is stripped away and the relevant sentence parts are isolated, it should be more obvious to an informed bilingual reader or listener that the translation or interpretation doesn’t reflect the original meaning.

Reordering and nesting changes both involve the linear arrangement of propositions in a sentence. Changes in semantic relations involve the hierarchical relations between propositions – whether a subordinate proposition is a semantic argument of, a modifier of or an adjunct to its parent – regardless of their linear order. Changes in one of these two dimensions can often involve changes in the other dimension as well. In translation or interpretation between languages with very different structure, a lot of reordering or nesting may be required in order to preserve the same hierarchical relations between propositions as in the original. In such language pairs, failing to reorder or to create or eliminate a nesting may result in a change in hierarchical relations.

For example, a Japanese translation which preserved the order of propositions in an original English text and was therefore incoherent would give low counts for linear changes (reordering and nesting changes). But it would give very high counts for the other indicator of difficulty, changes in semantic relations. That makes sense. Keeping propositions in the same order may require less syntactic effort than changing them round. But the fact that the semantic relations between propositions become distorted in the process suggests that the translator or interpreter has encountered difficulty in understanding or reproducing those relations.

A cleverer manipulation is illustrated in section 5.2.4, which discusses syntactic transformation as a tactic for interpretation between languages with very different structure. The example given there is of a complex Turkish sentence as actually spoken at a conference and of a hypothetical good English interpretation which preserves the linear order of propositions in the original sentence but changes all the hierarchical relations between them. Such a rendition would also give low counts for reordering and nesting changes, but a very high count for changes in semantic relations. In contrast, a structurally accurate rendition would give a zero count for changes in semantic relations, but very high counts for the reordering and nesting changes that would be required to preserve those hierarchical relations. Either way, the count for one or more indicators of difficulty would be much higher than in a similar sentence translated or interpreted between structurally similar languages.

This study doesn’t attempt to determine whether difficulty as reflected in changes in semantic relations is the result of necessity or choice. Klaudy (2004) distinguishes between necessary and optional cases of deliberately adding or removing words to make a translation more explicit or more implicit than the original. Some such changes might be counted as changes in semantic relations as defined in this study. But changes in semantic relations as defined here are generally much less intentional, making the distinction between necessary and optional changes hard to measure objectively. Plus there’s often likely to be a mixture of both constraints and choice when relations between propositions are changed. How much of the incoherent Japanese translation described above would be the result of structural difference between Japanese and English, and how much would be the result of “choice”? It would be nearly impossible to tell. For this study, the fact that such a translation would give a very high count for one of the indicators of difficulty – changes in semantic relations – is enough.

For Larson (1984), preserving the semantic relations between propositions, regardless of syntactic form, is central to the preservation of meaning in a successful translation. Accordingly, a change in semantic relations in translation or interpretation can be taken as a sign that the translator or interpreter has for some reason been unable to or chosen not to reproduce the original relations among propositions in the target language. This is the third indicator of difficulty measured in this study.

To give a better idea of what sort of changes we’re talking about and what effect they can have on meaning, some of the most common changes in semantic relations in translation or interpretation are illustrated below.

3.3.4.1 Common types of changes in semantic relations

What follows is a short list of what are, in my experience, the most common types of changes in relations between propositions in translating or interpreting complex sentences between languages with very different structure.

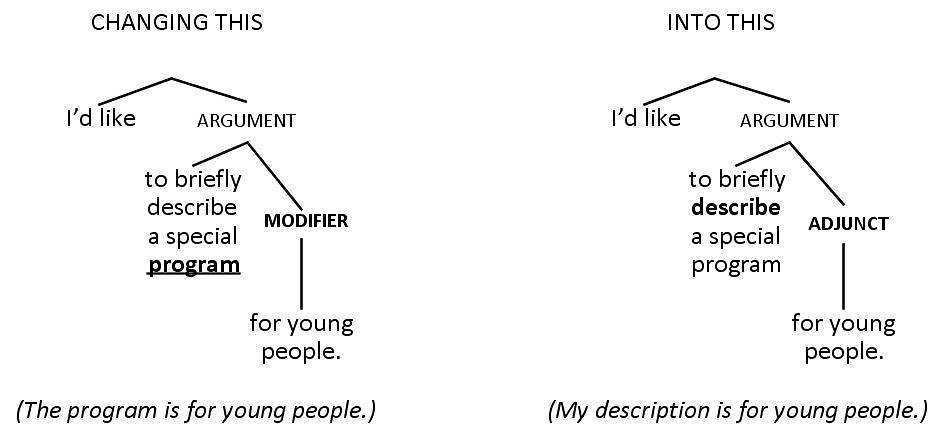

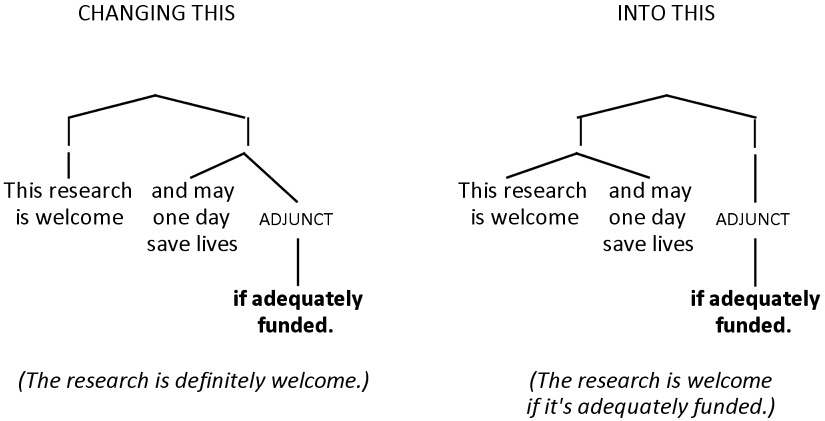

1. Changing a modifier of an argument into an adjunct of a predicate, as illustrated in figure 20

Figure 20

Changing a modifier into an adjunct

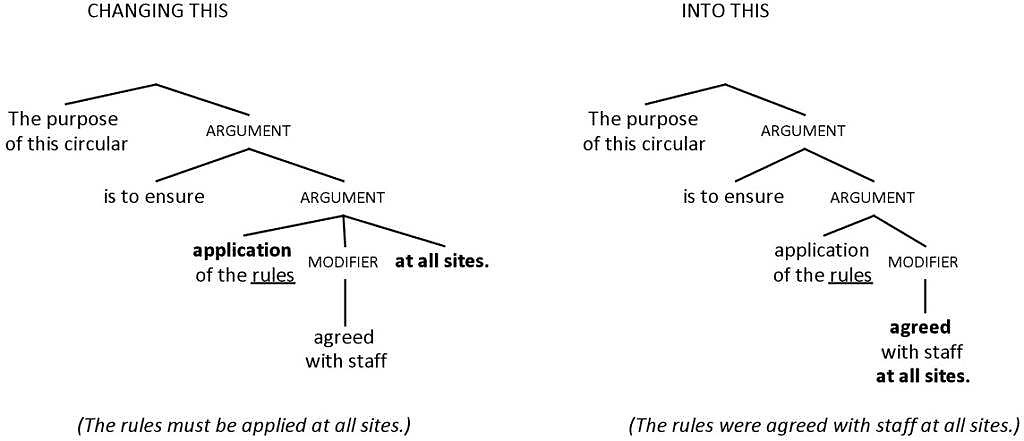

2. Linking an adjunct to a different predicate, as illustrated in figure 21

Figure 21

Linking an adjunct to a different predicate

3. Changing an argument of a subordinate proposition into an adjunct to the parent proposition, as illustrated in figure 22

Changing an argument into an adjunct

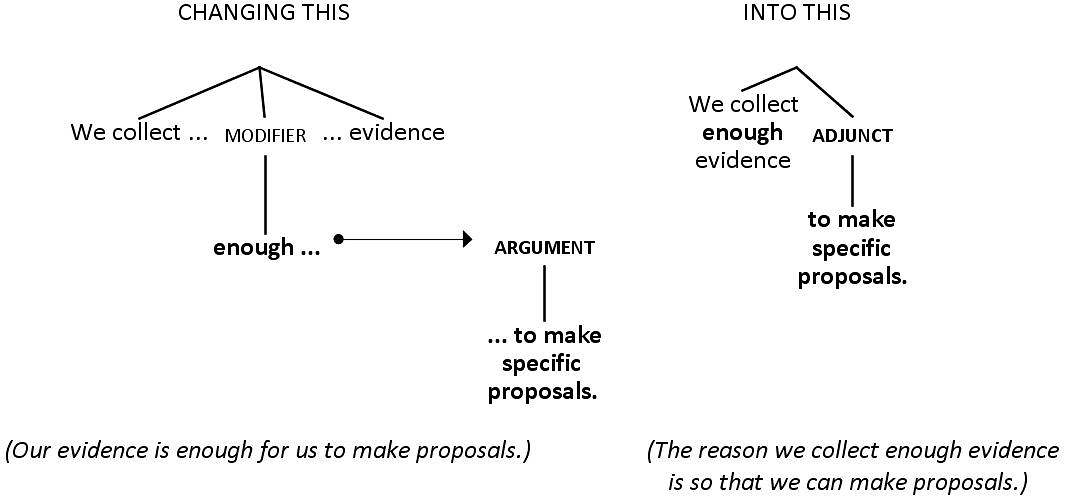

4. Changing a coordinate proposition into an argument, as illustrated in figure 23

Figure 23

Changing a coordinate proposition into an argument

5. Changing the scope of an adjunct, as illustrated in figure 24

Figure 24

Changing the scope of an adjunct

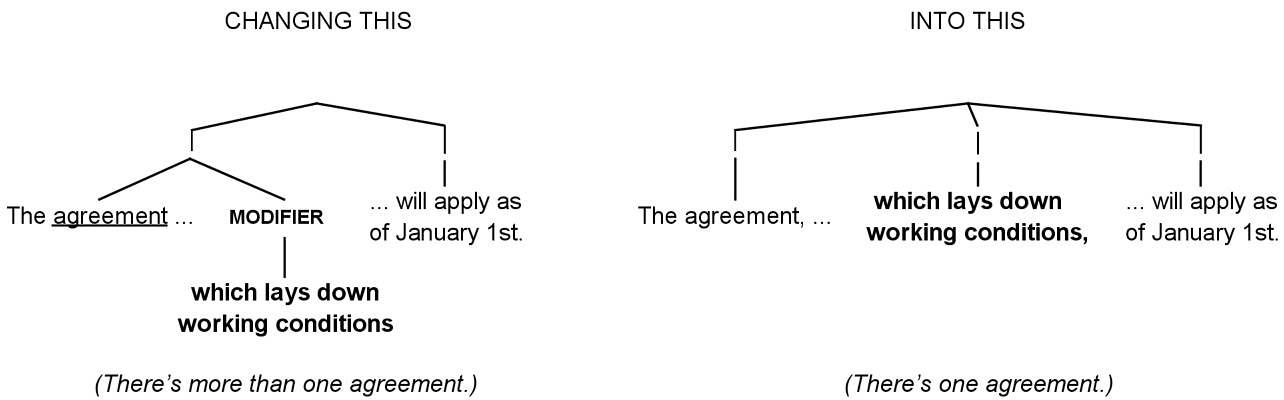

6. Changing a restrictive modifier into a descriptive, functionally independent proposition, as illustrated in figure 25

Figure 25

Changing a restrictive modifier into a descriptive, functionally independent proposition

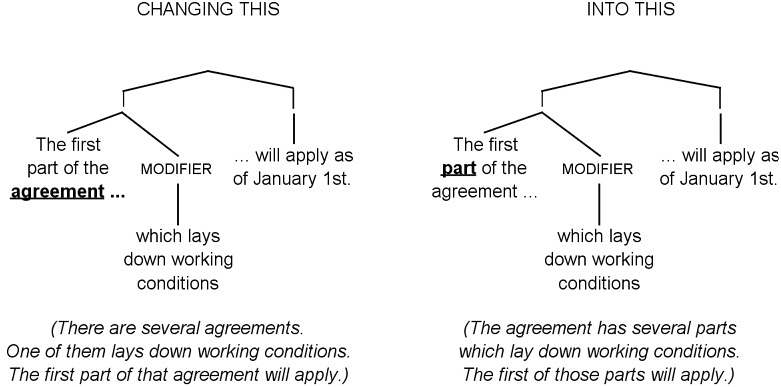

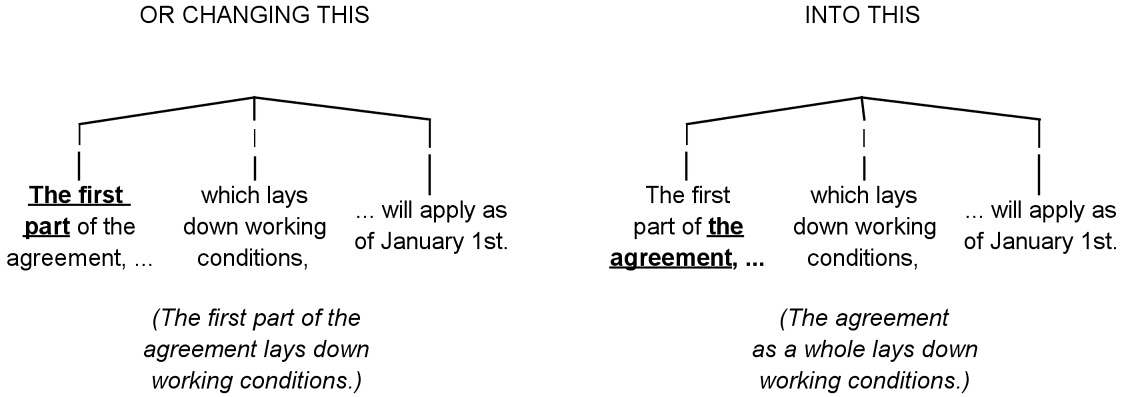

7. Changing the scope of a restrictive modifier or of a descriptive, functionally independent proposition, as illustrated in figures 26 and 27

Figure 26

Changing the scope of a restrictive modifier

Figure 27

Changing the scope of a descriptive, functionally independent proposition

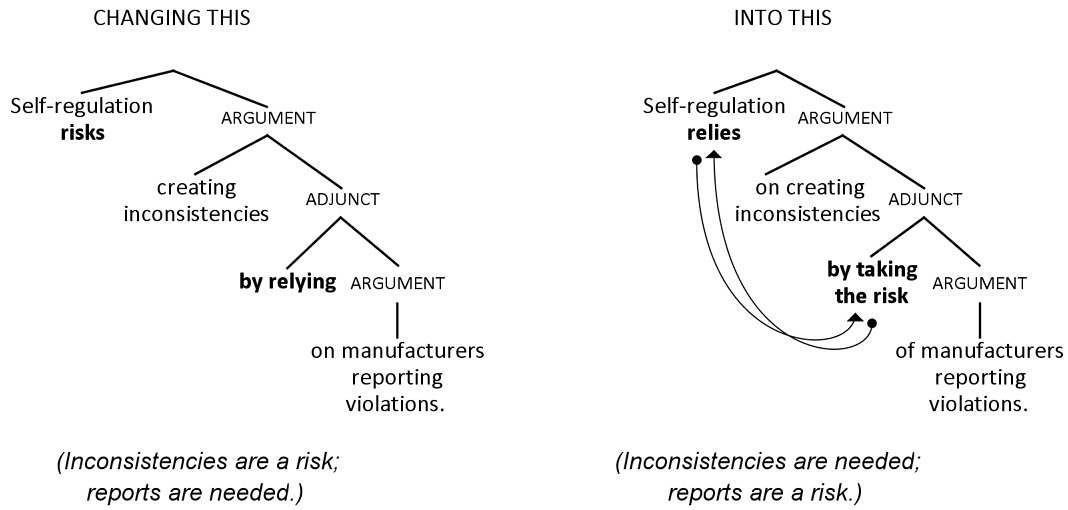

8. Switching predicates with a shared argument, as illustrated in figure 28

Figure 28

Switching predicates with a shared argument

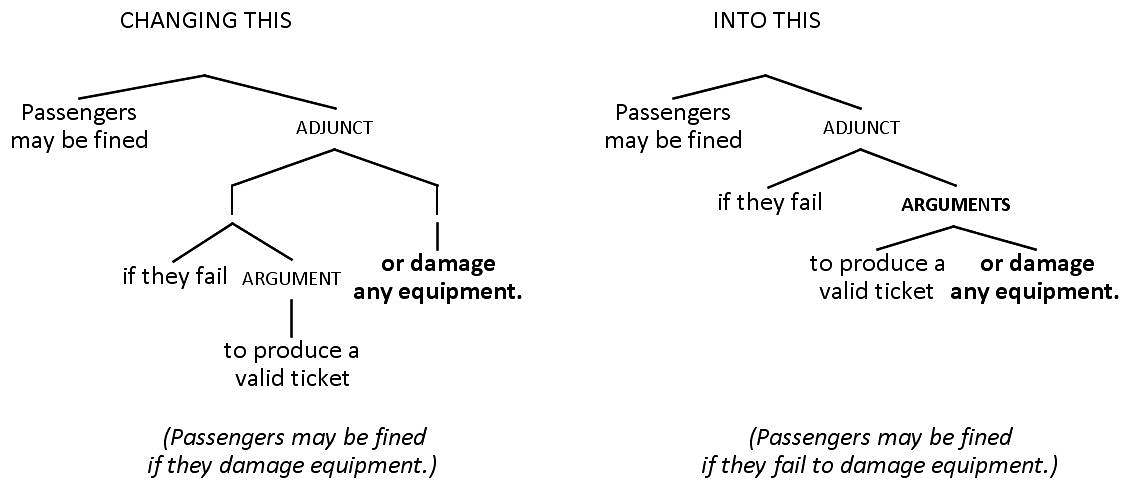

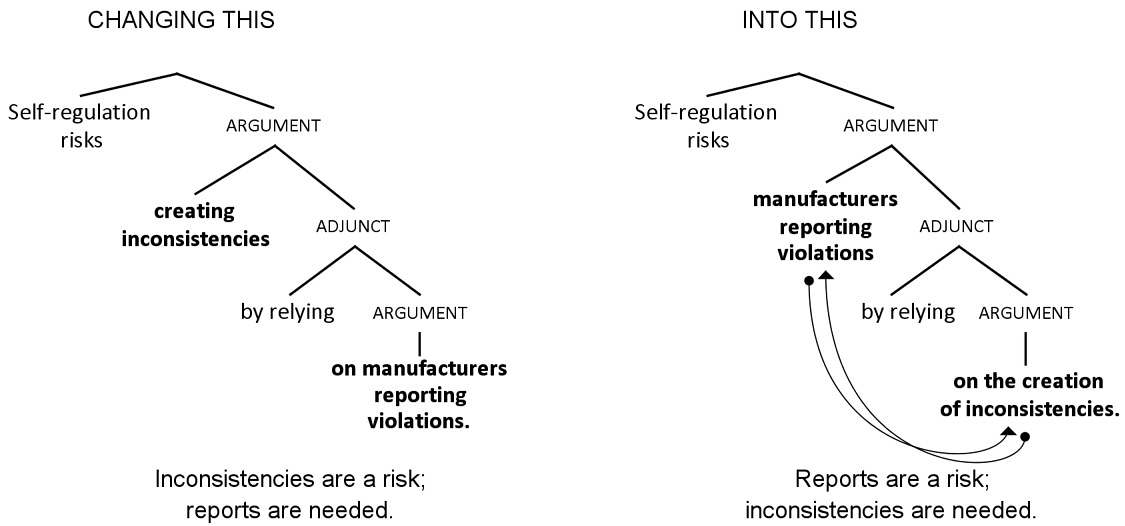

9. Linking arguments to different predicates, as illustrated in figure 29

Figure 29

Linking arguments to different predicates

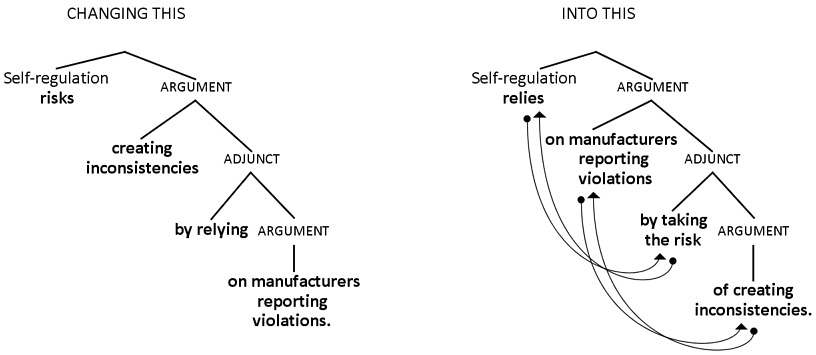

10. Switching predicates with a shared argument (No 8 above) and at the same time linking arguments to different predicates (No 9 above), as illustrated in figure 30

Figure 30

Switching predicates and linking arguments to different predicates

In my experience, changes like these in semantic relations are common in translation or interpretation of complex sentences between languages with very different structure. Such changes generally occur in sentences more intricate than the examples given above. Also, several such changes can be combined and interwoven, making them hard to identify and analyze. Some of these changes can of course occur in translation or interpretation between structurally similar languages too. But they may have a greater effect on how propositions are ordered and linked, and therefore be more liable to distort meaning, in a language pair with very different structure.

This chapter has presented a method for parsing complex sentences, a representative corpus of such sentences, as well as the main variables analyzed in this study. The next chapter looks at how values for those variables are counted and analyzed for each sentence in the corpus, then presents the results of that analysis.

← 3.3.3 Nesting changes

→ 4. Analysis and results