3.1 Semantic parsing

This section summarizes the general features of a method for parsing complex sentences into component propositions and indicating the functional relations between those propositions. That method is then applied to each sentence in the corpus, to record values for the variables fed into the statistical analysis. A detailed explanation of the semantic parsing method can be found in annex I. The method is also described briefly below.

3.1.1 The reason for semantic parsing

As explained in the literature review, in section 2.2.1, the unit of analysis chosen for this study is the semantic proposition. Dividing complex sentences into clauses or similar syntactic units wouldn’t capture the semantic equivalence between a proposition as expressed in a clause in one language and the same proposition as expressed in a clause-like nominal structure in another language. An example can be seen in the original English sentence in (1) and a Japanese translation of the same sentence in (2).

(1) After we arrived, we were taken on a tour of the old town.

(2) 到着後、旧市街のツアーに連れて行かれました。

Tōchaku go, kyū shigai no tsuāni tsurete ikaremashita.

(lit.) “After arrival, we were taken on a tour of the old town.”

A syntactic approach to complex sentence parsing would risk overlooking the semantic equivalence between the initial clause in (1) and the initial postpositional phrase in (2). But the features taken in this study as indicators of difficulty involve comparing the relations between segments of original complex sentences and corresponding segments of the same sentences in translation or interpretation. So a syntactic method of segmenting could well have yielded higher counts than a semantic method for the identified indicators of difficulty overall, and in some language pairs more than in others. That could have left the door open to suggestions of certain language pairs appearing to be associated with artificially high counts for the indicators of difficulty, just because translation or interpretation in those pairs may tend to involve more clauses being rendered as nominal structures than in other pairs, or vice versa.

To avoid any such suggestion, a semantic method of segmenting complex sentences has been developed for this study. That method treats all syntactic ways of saying the same thing as equal. So it yields lower counts than a syntactic method would for the indicators of difficulty overall. More importantly, it shows lower degrees of difference between various language pairs in counts for those indicators of difficulty than would be the case with a syntactic approach. There are still striking differences in rates recorded for the indicators of difficulty in some language pairs compared to others, as we’ll see in the next two chapters. But the effect on those differences of some languages tending to prefer nominal structures to clauses has been eliminated by applying the semantic parsing method developed for this study.

3.1.2 Relations between propositions

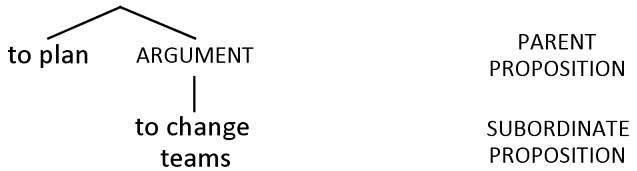

One proposition can be subordinate to another, parent proposition, as illustrated in figure 1.

Figure 1

Parent and subordinate propositions

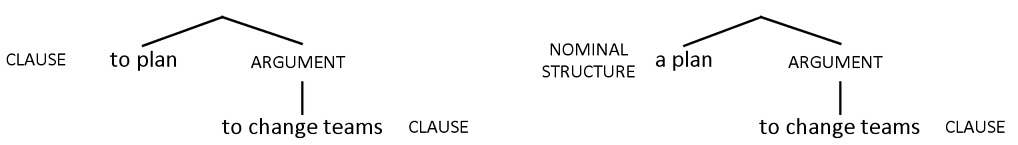

Each of the propositions in figure 1 can be expressed as a clause or as a clause-like nominal structure. The relations of semantic hierarchy between predicates and arguments in figure 2 are the same.

spacer

Figure 2

Parent and subordinate propositions with the same hierarchical relations

For simplicity and clarity, the parse trees used here include an overt link between propositions on the same branch as one of the propositions. If one proposition is subordinate to another, an overt link between them – like “for” in the last tree in figure 2 – is included on the same branch as the subordinate proposition.

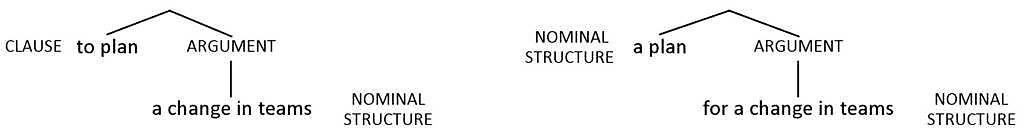

The relations between a parent and a subordinate proposition can sometimes be recast with minimal differences in meaning from one syntactic form to another, as illustrated in figure 3.

Figure 3

Propositions with similar hierarchical relations

This kind of switch is possible within a language, as in the examples in figures 2 and 3. It’s also possible in translating or interpreting a message from one language to another. A method of analysis based on propositions, where clause-like nominal structures are treated in the same way as finite and non‑finite clauses, reflects the semantic similarities between the different syntactic forms which various languages can use to describe an event or situation. It also helps highlight whether the hierarchical relations between propositions, whatever their syntactic form, are preserved in translation or interpretation.

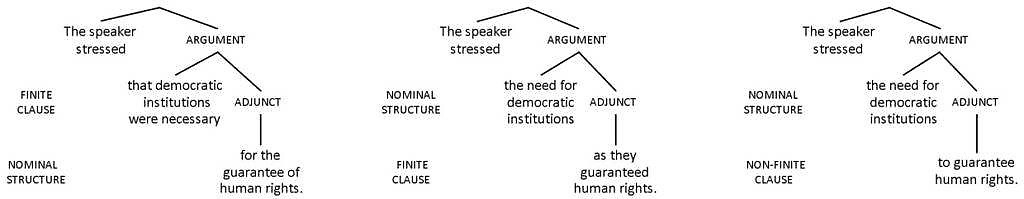

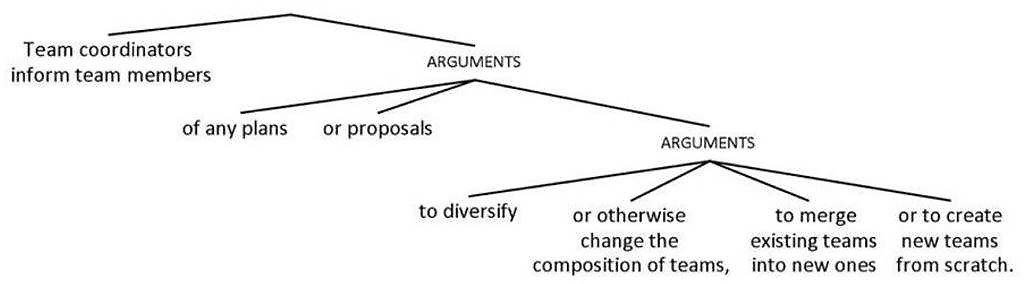

Figure 4 shows a parse tree of the hierarchical relations between propositions in a complex sentence. The labels on the nodes indicate the semantic role of each subordinate proposition in relation to its parent. In this sentence, each subordinate proposition is a semantic argument of its parent.

Semantic parse tree of complex sentence

In the parse tree in figure 4, the propositions in the bottom row function as arguments of the underlying verbs “plan” and “propose,” from which the nominal predicates in the second row are derived. “Plans” and “proposals” are treated here as process nominals – that is, predicates with argument structure. In contrast, “composition” in the second proposition in the bottom row is treated as a result nominal with no argument structure – just as if it said “names” or “numbers” instead of “composition.” The distinction between result nominals and process nominals is sometimes fuzzy. This distinction is discussed in the detailed presentation of the semantic parsing method, in section 1.7 of Annex I.

The sort of semantic parse tree used here is similar in appearance to syntactic parse trees in the tradition of generative grammar. The main difference is that each leaf on the trees used here shows the syntactic expression of a semantic proposition. This method of segmentation and display allows for one‑to-one comparison of corresponding propositions in translation and interpretation, however they’re expressed in different languages. It also helps highlight problems in transferring complex sentence structure from one language to another.

The semantic parsing method illustrated briefly above is a technical tool developed for the purpose of this study. That method would be need to be refined if it were being proposed as an alternative approach to discourse segmentation in its own right. But as a technical tool, it’s more than adequate for its purpose, which is to segment complex sentences in a way that shows greater correspondence between functionally equivalent phrases than other established approaches to segmentation, like division into clauses or similar syntactic units. A detailed explanation of the semantic parsing method developed for and used in this study can be found in annex I.

← 3. Method and data

→ 3.2 Corpus