5.2 Tactics for interpretation between

languages with very different structure

This study has found preliminary evidence of associations between structural difference in a language pair and recorded rates for indicators of difficulty in translating or interpreting complex sentences in that pair. A natural question is: “What can be done about it?” In one sense, the unsatisfying answer is: “Not much.” Translating and interpreting complex sentences between languages with very different structure can just be objectively very hard. The main purpose of this study is to confirm and raise awareness of that difficulty, not to suggest that it can be mitigated in any substantial way.

Especially under the working memory constraints of simultaneous interpretation, the difficulty of transferring coherent content between languages with very different structure can become enormous. That can make it impossible to render a complex speech with anything approaching the completeness and accuracy of interpretation between structurally similar languages. The best thing an interpreter in this situation can hope for is to get a written copy of the speech or speaking notes beforehand, if there is one. Simultaneous interpretation in any language pair can be easier with a written text than without one, because the interpreter can do a partial sight translation while interpreting. But sight translation is often much trickier in a language pair with very different structure than in a structurally similar pair. That makes it all the more important for an interpreter working in such a language pair to try to get a copy of any text long enough beforehand to prepare it.

Of course, despite our best efforts, it’s often not possible to get a copy of a text. In that case, it’s all the more crucial for the interpreter to be equipped with tactics to make the best of what can seem like an impossible task. Some of the main tactics interpreters working between languages with very different structure can use in trying to cope with that task are discussed below. But first, a word about working memory and different proposed approaches to interpretation.

5.2.1 Working memory and interpretation

If reordering and nesting changes are a headache for translators, they can be a nightmare for simultaneous interpreters. In a proper written translation between languages with very different structure, the propositions of a complex sentence may need to be rearranged in inverse or scrambled order, and multiple nestings may need to be constructed or taken apart. For a simultaneous interpreter trying to interpret a complex sentence in such a language pair, doing that to the same extent can be impossible because of the natural limits to working memory.

When transferring a complex sentence between structurally similar languages, an interpreter can start to process and reformulate the first proposition as soon as they’ve heard it, or even part of it. That frees up working memory, so they can go on to the next proposition. Each new proposition is linked to the one before it, parallelling their order in the original version of the sentence. That means a good interpreter working between, say, two European languages may be able to produce a result that sounds more or less like a written translation and that accurately reflects the content and coherence of the original speech. The most structural work they’ll need to do will be to retain or anticipate the odd element (like a clause-final verb in German) over a short distance here or there.

But that can be impossible in simultaneous interpretation between languages with very different structure. An interpreter trying to interpret complex sentences between a right-branching and a left-branching language can face a huge cognitive challenge. In many cases, producing a structurally accurate rendition would require the interpreter to hear an entire original sentence, before starting to rearrange its propositions and recast the links between them. Just understanding a sentence with multiple nestings in real time can be hard, as we’ve seen, especially without a written copy of what’s being said. Doing that, plus retaining the entire sentence, rearranging its content, then producing an intelligible and accurate interpretation, all while trying to retain and process the next incoming complex sentence, can be a task beyond the working memory capacity of the normal human brain.

Gile (2009) proposes an often-cited model dividing the task of simultaneous interpretation into three efforts –listening, remembering and speaking. Interpreting complex sentences between structurally different languages can require devoting such a huge amount of brainpower to structural management that this could possibly be seen as a fourth effort, seriously affecting the cognitive capacity that an interpreter has available to devote to the other three tasks.

Seleskovitch and Lederer’s (1989) “théorie du sens” or “interpretive theory” claims that a good interpreter “deverbalizes” incoming meaning and then reformulates it as a whole in the target language. Similarly, Dam (2001: 27) describes “meaning-based” interpretation as relying on a “non-verbal” representation of meaning. In practice, this means that an interpreter can generally achieve more natural wording and coherent structure in the target language by processing the incoming message in larger chunks, as single units of meaning in a larger context, rather than interpreting words and shorter phrases separately. Put that way, it’s hard to find fault with the interpretive theory and meaning-based interpretation as a guideline. But restating meaning-based interpretation in terms of the size of speech chunks processed before reformulation also helps reveal its limits.

I can process a whole speech chunk before reformulating it, if I can retain it. The more information that chunk contains, the harder it will be to retain. If I hear a long sentence with many propositions and am asked to retain its content, I may be able to retain the overall message, but I probably won’t remember each element of each proposition. We can generally retain only a certain number of items – Miller (1956) says around seven – in working memory. That limit can be taken as applying to items in a list, elements of propositions, or general notions of events or situations described.

That’s where meaning-based interpretation, as good as it is as a guideline, may break down, and form-based interpretation, necessitated by structural constraints, may need to take over. Because the ordinary human brain can’t retain every element in a long, complex sentence. If we go for the big picture, we’re likely to lose some of the detail. And an interpreter needs to try to reproduce both – the big picture and the detail.

For interpreting between structurally similar languages, like two European languages, where propositions follow each other in the same order, the more an interpreter succeeds in keeping a manageable gap from the speaker, the more flowing, natural and meaning-based their interpretation is likely to be. But that may not work for interpreting a long, complex sentence between languages with very different structure, where propositions often appear in reverse or jumbled order. In such conditions, an interpreter may choose to listen to the entire sentence before starting to reformulate it, in which case they’re liable to leave out some detail. Or, more likely, they’ll listen to one or two propositions and then start to interpret. In that case, they’ll have to manage the structural problems created by the fact that an accurate interpretation would have to start with the last proposition in the original version, which they won’t have heard before starting to produce their rendition of the sentence.

This study is about demonstrating comparative difficulty in translation or interpretation, not about proposing solutions. Still, given the limits of working memory and of meaning-based interpretation, the challenges of simultaneously interpreting complex sentences between languages with very different structure are so specific and so acute that it’s worth mentioning some tactics interpreters can use to cope with the challenges of complex sentence structure. Some of the most important such tactics are sentence division, anticipation and syntactic transformation. These tactics are discussed briefly below.

5.2.2 Sentence division

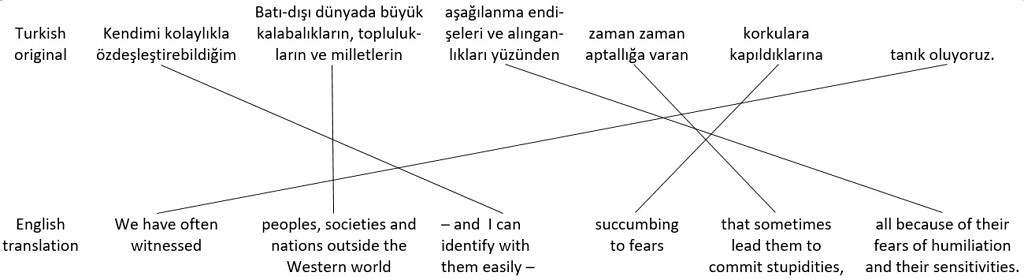

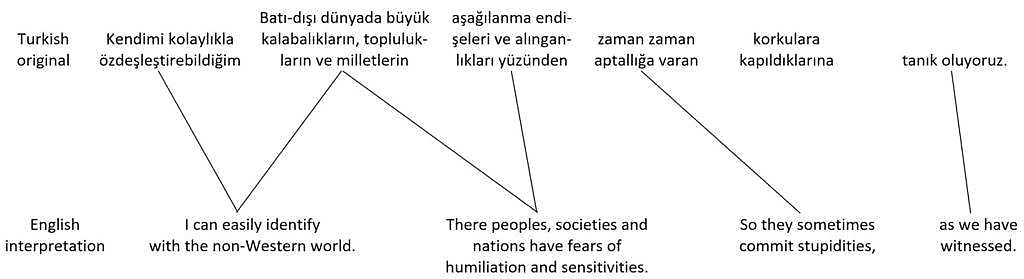

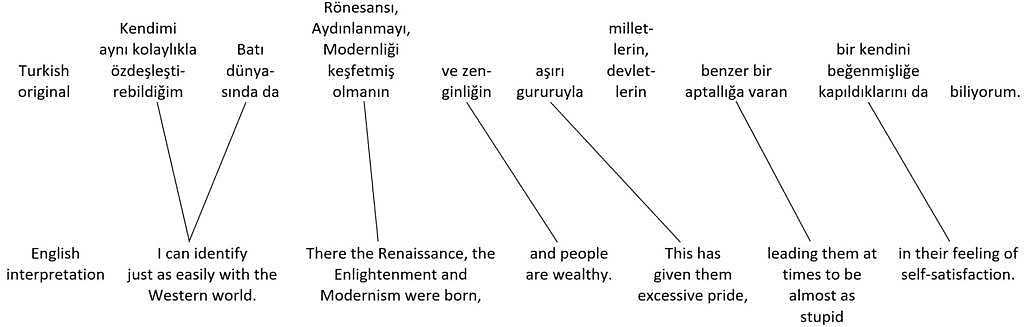

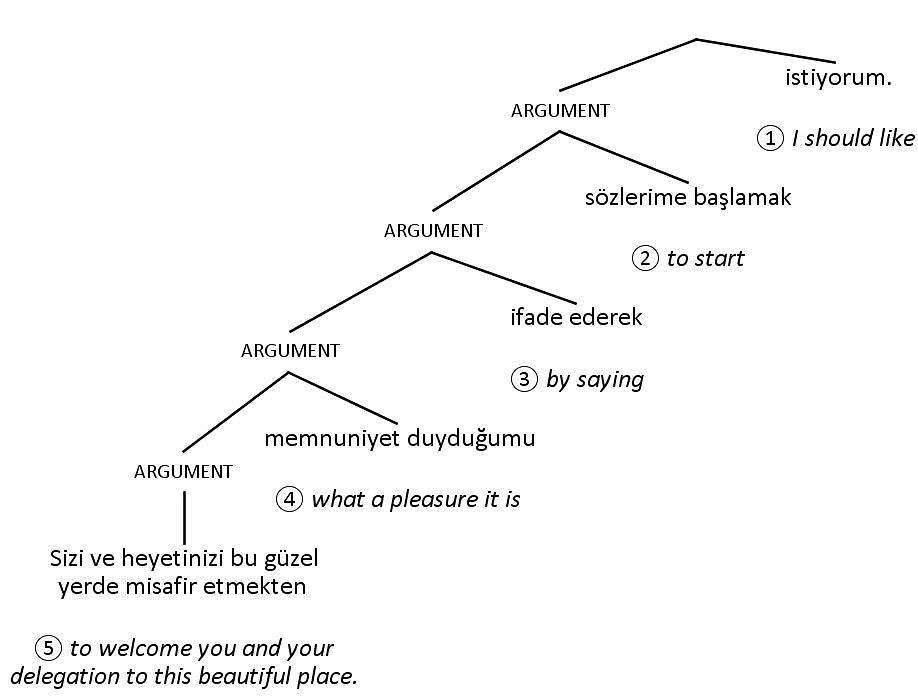

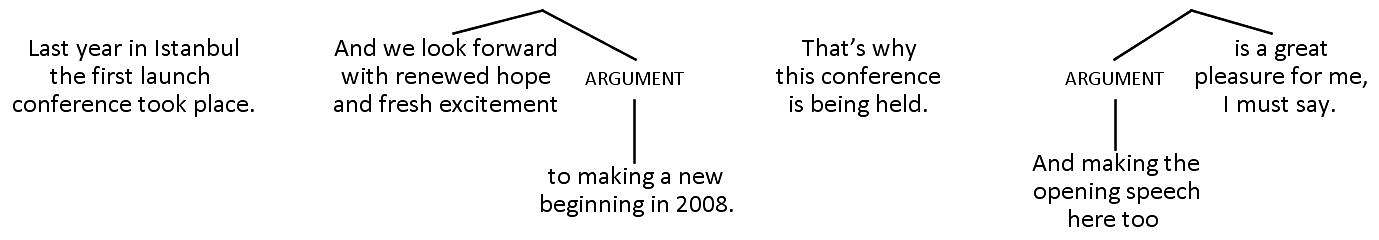

One tactic interpreters can use to reduce the need for reordering propositions and to maintain a manageable burden on working memory is to divide longer sentences into shorter ones. For example, figure 41 shows two sentences from the 2006 Nobel Literature Prize Lecture by author Orhan Pamuk, as spoken in Turkish, along with a nice English translation by Maureen Freely. Propositions are grouped separately, with lines connecting the corresponding propositions in the original and translated versions. Syntactically split propositions are shown in separate groups with separate lines.

Original Turkish sentences and English translations

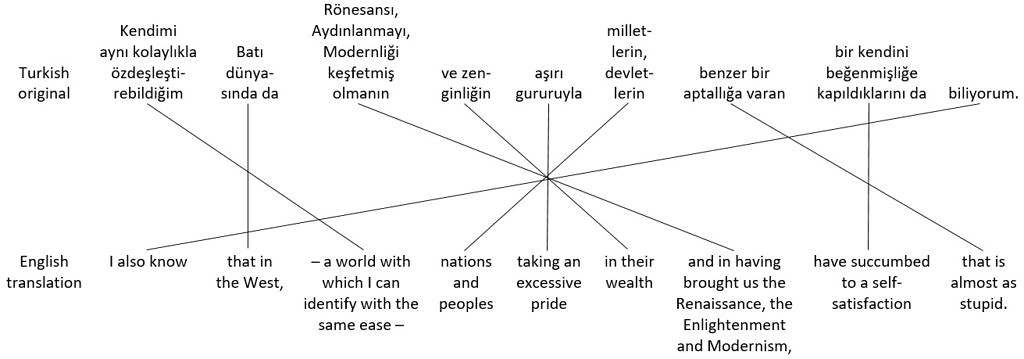

Compared to the original Turkish sentences, the order of propositions in the English translations is completely jumbled. Unless an interpreter had a written copy of the speech to prepare beforehand, it’s unlikely that they could produce an interpretation anything like the nice written translation in real time, with the main propositions – which come at the end of the Turkish sentences – in the right places at the beginning of the English sentences, and with all the other pieces in the right places too. Instead, the interpreter might try dividing the original Turkish sentences shown in figure 41 into shorter ones. With luck, they might produce something like the hypothetical English interpretation of the two sentences shown in figure 42.

Original Turkish sentences and hypothetical English interpretation

Figure 42 illustrates how the two sentences from the original Turkish speech shown in figure 41 could been divided into six separate sentences in a hypothetical English interpretation. The advantage of doing this is that the propositions end up in more or less parallel order in interpretation to their order in the original version. One disadvantage is that this can lead to lower register, because of flatter structure. Another disadvantage is that some detail may be left out.

5.2.3 Anticipation

Another tactic that can be used in interpreting complex sentences between languages with very different structure is anticipation – guessing and interpreting parts of a sentence before hearing them. This can be useful in interpreting from a left‑branching language like Turkish or Japanese into a right-branching one like English. That’s because the functional information necessary to begin formulating a sentence in a right-branching language may come only at the end of the sentence in a left-branching one.

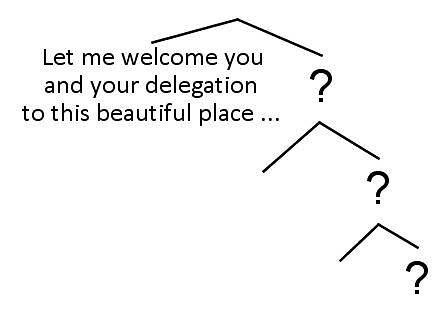

For example, figure 43 shows a parse tree with a hypothetical opening sentence from a Turkish speech. The numbers show the order the branches need to be read in to make sense in English.

Figure 43

Hypothetical original Turkish sentence

An interpreter wishing to reproduce the Turkish sentence in figure 43 in English might decide to begin speaking after hearing the first clause (branch number 5 in the tree). They might anticipate the main subject with something non‑committal, like the hypothetical beginning in figure 44.

Hypothetical interpretation,

anticipating first words

The interpreter would then have to accommodate the rest of the sentence, with appropriate subordinate or coordinate structures. The advantage of anticipating elements like this is that the interpretation ends up in more or less parallel order to the original version – similarly to sentence division. The disadvantage is the risk of guessing wrong and having to correct oneself.

5.2.4 Syntactic transformation

Perhaps the most sophisticated tactic for interpreting complex sentences between languages with very different structure is syntactic transformation. This involves changing the relations among propositions so that they come out in interpretation in more or less parallel order to the original.

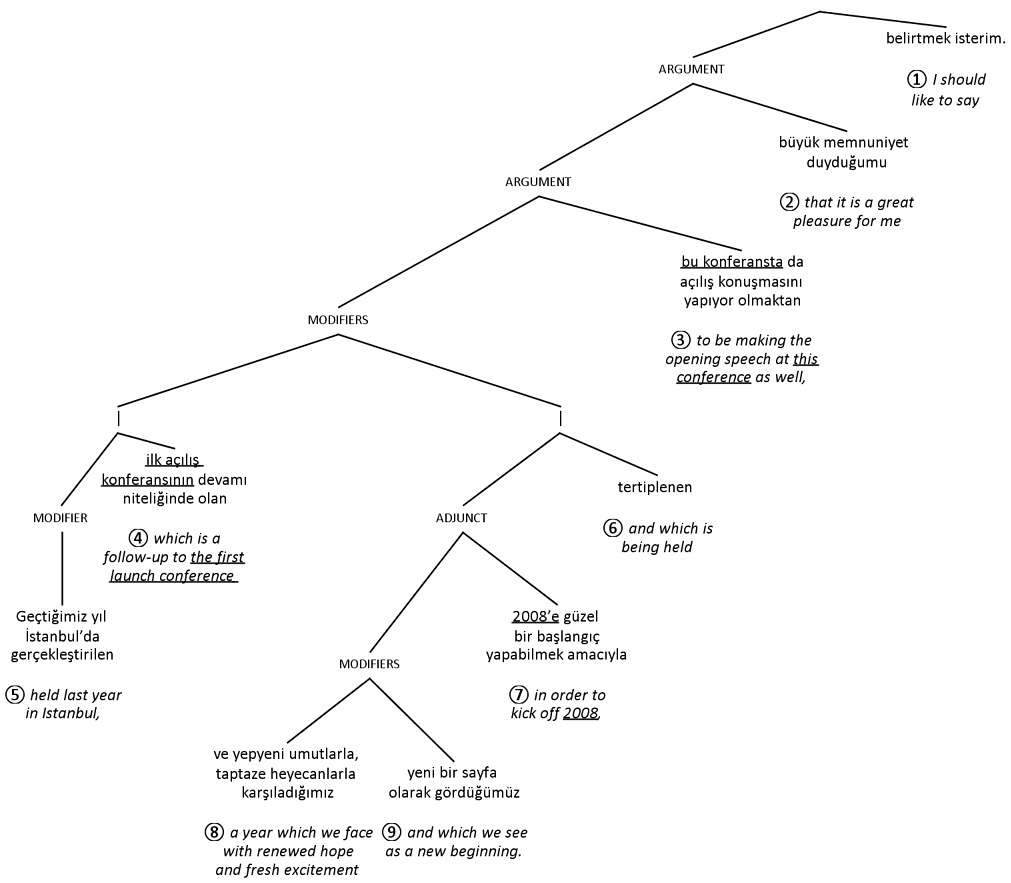

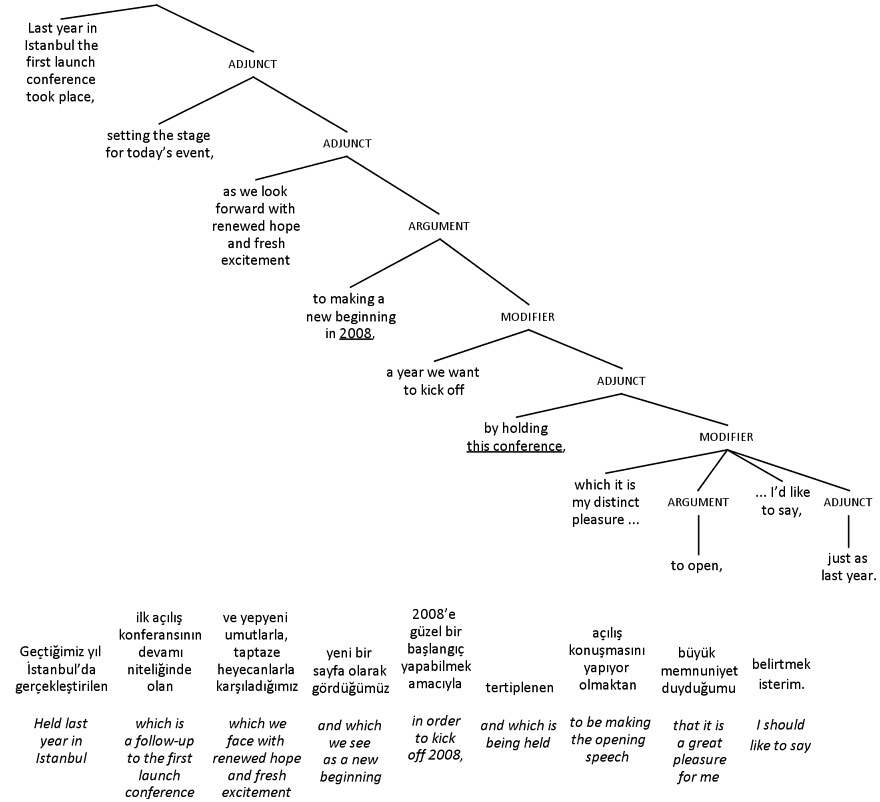

To see how this can work, let’s look at an example of a complex sentence for interpretation. Figure 45 shows a parse tree with the beginning of a speech given in Turkish by the Vice President of the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Turkey, at a conference in 2008. The numbers show the order the branches need to be read in to make sense in English.

Figure 45

Original Turkish sentence

A structurally accurate English version of the Turkish sentence in figure 45 is shown on the parse tree in figure 46.

Structurally accurate English version of sentence

An interpreter wishing to interpret a Turkish sentence like the one in figure 45 into English might try starting with the same approach as illustrated in figure 44 – anticipating the main subject. The problem is that the main subject of the sentence in figure 45 comes at the end of a long Turkish sentence, after lots of subordinate clauses which don’t lead the listener towards the speaker’s main point. This makes anticipation much harder and calls for an alternative tactic.

How about sentence division? Because of limited working memory, an interpreter interpreting a Turkish sentence like the one in figure 45 into English might try dividing it into smaller sentences. The result could be similar to the hypothetical interpretation shown in figure 47.

Figure 47

Hypothetical English interpretation with sentence division

The hypothetical interpretation based on sentence division, shown in figure 47, is easier to produce in real time than a structurally accurate interpretation would be. But it sounds a lot choppier and flatter than the original. And it’s missing a lot of the detail.

Alternatively, a skilled interpreter might try to change the structure of the original version of the sentence. Ideally, they might manage to construct a sentence similar to the original version in formality and complexity, without changing the linear order more than limited working memory allows. They could do this through a series of clever structural transformations, producing something like the hypothetical English interpretation shown in figure 48. The original Turkish sentence is shown under the tree, segmented and glossed. Nearly every proposition in the hypothetical English interpretation corresponds to the one directly below it in the Turkish original.

Figure 48

Hypothetical clever English interpretation of sentence, parallelling original Turkish version

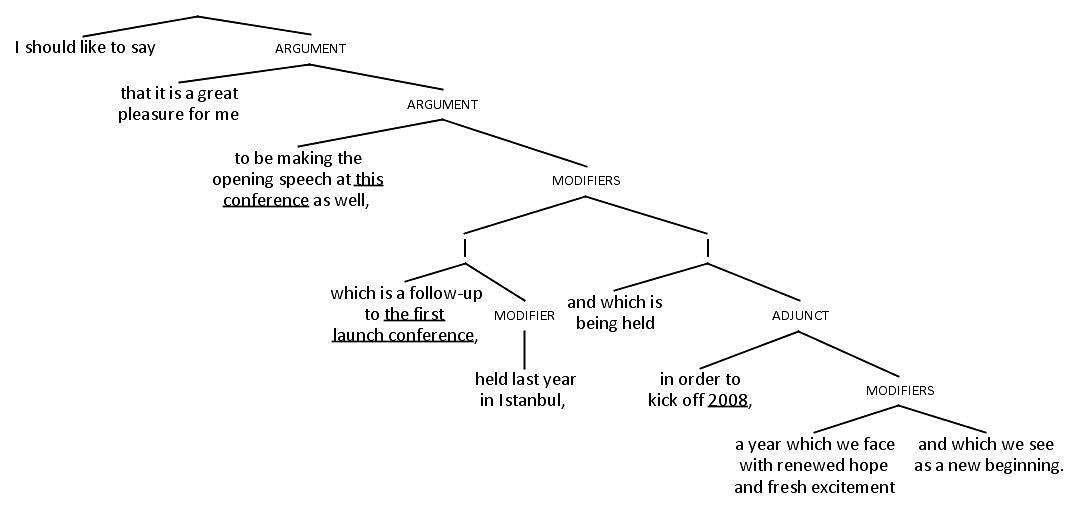

The linear order of propositions in the hypothetical English interpretation in figure 48 is nearly parallel to the order of propositions in the original Turkish version of the sentence. The result isn’t choppy or flat, and more or less manages to reflect the rhetorical style of the original speech. But … all the syntactic relations between clauses have been inverted. The syntactically lowest clause in the original sentence has become the syntactically highest clause in the interpreted version, and vice versa.

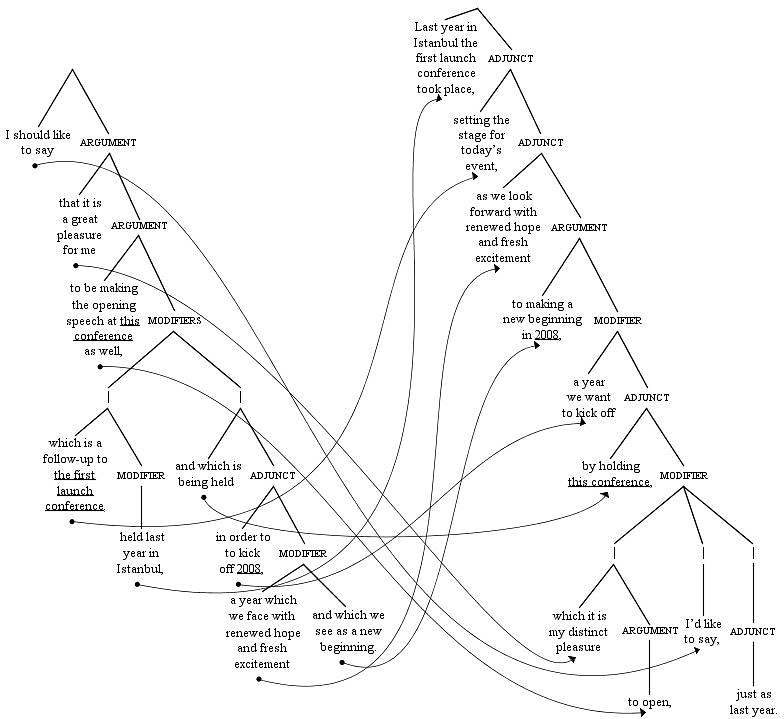

Figure 49 shows parse trees comparing a structurally accurate English version and the restructured English version produced by our hypothetical clever interpreter. The arrowed lines connect corresponding propositions in the two versions, showing the changes in syntactic relations between them.

Structurally accurate English version Cleverly reconstructed interpretation

As with the structural changes we saw before from sentence division and anticipation, the sort of structural distortion due to syntactic transformation that’s illustrated on the right-hand side of figure 49 may be acceptable in interpretation, but would be less acceptable in written translation. And of course this hypothetical interpretation is an idealized case. A real interpreter would be unlikely to execute such fancy syntactic footwork so elegantly in practice. Plus, such mental gymnastics, even if possible, could only be as neat as shown here if the original propositions were each in one piece syntactically, as they happen to be in this case. In a different complex sentence in a left‑branching language like Turkish, some of the original propositions could well be split by long nested propositions, which could themselves be split by other propositions. In that case, anything approaching an accurate or elegant interpretation in real time could be next to impossible.

This section has briefly presented some tactics which simultaneous interpreters can use when interpreting complex sentences between languages with very different structure. These tactics can be hard to apply, and the result is often less than ideal in terms of content or style. But that effort and that compromise can pay off, by reducing the burden on an interpreter’s working memory.

This brief discussion of interpreting tactics brings us to the end of this study. The main conclusions are summarized in the next section.

← 5.1 Summary of findings

→ 5.3 Conclusion