Annex I – Semantic parsing

3. Shifting focus

3.1 A dynamic view of complex sentences

The relations between clauses in a complex sentence are often modeled as fixed relations between different hierarchical levels. But this study sees those relations as shifting. As Langacker (2014: 69) puts it, “grammar proceeds through time…. The static formulas and diagrams employed in describing it should not obscure the fact that grammar is something that happens” (emphasis in original). His dynamic view of cognitive grammar posits a “primary window” of attention, which opens successively onto each clause in a chain. At any stage in the chain, that window only needs to be big enough to contain one clause, plus a “mental space” for the next clause, establishing a relation of equal or unequal salience between them.

This study adopts the idea of successive windows of attention and adapts it to the analysis of relations between semantic propositions, whether expressed in clauses or any other syntactic form. Rather than trying to shoehorn each proposition into a fixed status of providing background or salient information, we can see the focus of attention as shifting as a sentence moves forward. This is a key feature of the semantic parsing method used here. An example can be seen in (139).

(139) This is a great book, which all new parents should read.

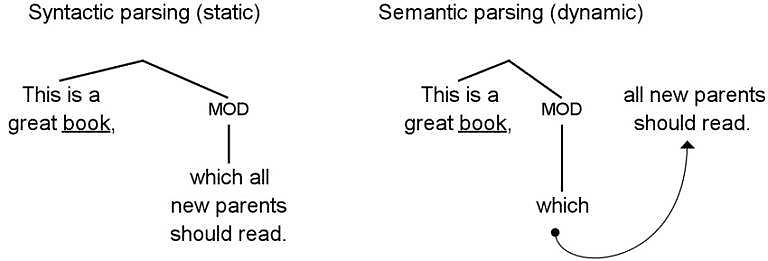

The second clause in (139) is a non-restrictive relative clause. Ramm (2008) characterizes such clauses as functionally coordinate rather than subordinate. As (139) moves forward, the focus of attention can be seen as shifting, as illustrated in figure 89.

Figure 89

Syntactic vs semantic parsing of subordinate clause which makes an assertion

On the parse tree on the right in figure 89, the link “which” is shown on a separate leaf at a lower level, because it introduces a subordinate clause. The rest of the clause it belongs to is shown as moving up to the top level of the tree, to indicate that it expresses a functionally independent proposition.

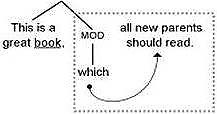

According to Langacker (2014: 14), such clauses show “prosodic seriality,” suggesting a “flat structure with no internal grouping.” He sees a sequence of such clauses in a sentence as requiring “only local connections, with no more than two clausal processes appearing in any single window” (pp. 26-27). The window for each proposition holds all the elements needed to process that proposition. In the sentence in (139), a first processing window opens onto the assertion that the book being referred to is great. This is shown in (140) and illustrated in figure 90.

(140) This is a great book, (isn’t it?) …

Figure 90

Window opens

The next processing window opens onto the assertion that all new parents should read the book, as shown in (141) and illustrated in figure 91.

(141) This is a great book, which all new parents should read, (shouldn’t they?)

Figure 91

First window closes, next one opens

In a sentence like (139), as illustrated in figures 90 and 91, a processing window never needs to be bigger than a single proposition plus a link. That’s because the first proposition with its predicate and arguments can already be processed and closed before the link. After that, the next proposition with its predicate and arguments can also be processed and closed. Each proposition in the sentence can be seen in turn as an assertion, and thus as functionally independent, even though the second proposition is expressed in a subordinate clause.

Non-restrictive relative clauses aren’t the only type of subordinate clause which can make an assertion. In European languages, various links which are syntactically subordinating but introduce propositions making assertions are common in everyday speaking and writing. They can be used to create a chain of assertions in a sentence, with a processing window opening onto each proposition in turn, then closing, as a new window opens onto the next one.

To illustrate this, consider a hypothetical sentence like (142), which unfolds progressively as the speaker thinks of what to say next. (The same sentence was given as an example in the section on logical order in the epilogue.)

(142) My wife’s learning Japanese, because she loves Japan, which has always been her favorite place to visit, although she’s always felt she could get more out of it if she spoke the language, which, as she’s finding out, is a never-ending journey of discovery into a culture that holds endless fascination and startling beauty for the learner.

Is (142) mainly about the speaker’s wife learning Japanese? Or about her loving Japan? Or Japan being her favorite place to visit? Or her wanting to speak the language? Or her finding out what that’s like? Or the language being a constant discovery? Or the culture being fascinating and beautiful? The tag question test confirms that the sentence can be about each of these things in turn, as shown in (143).

(143) My wife’s learning Japanese (isn’t she?), because she loves Japan (doesn’t she?), which has always been her favorite place to visit (hasn’t it?), although she’s always felt she could get more out of it if she spoke the language (hasn’t she?), which, as she’s finding out (isn’t she?), is a never-ending journey of discovery (isn’t it?) into a culture that holds endless fascination and startling beauty for the learner (doesn’t it?).

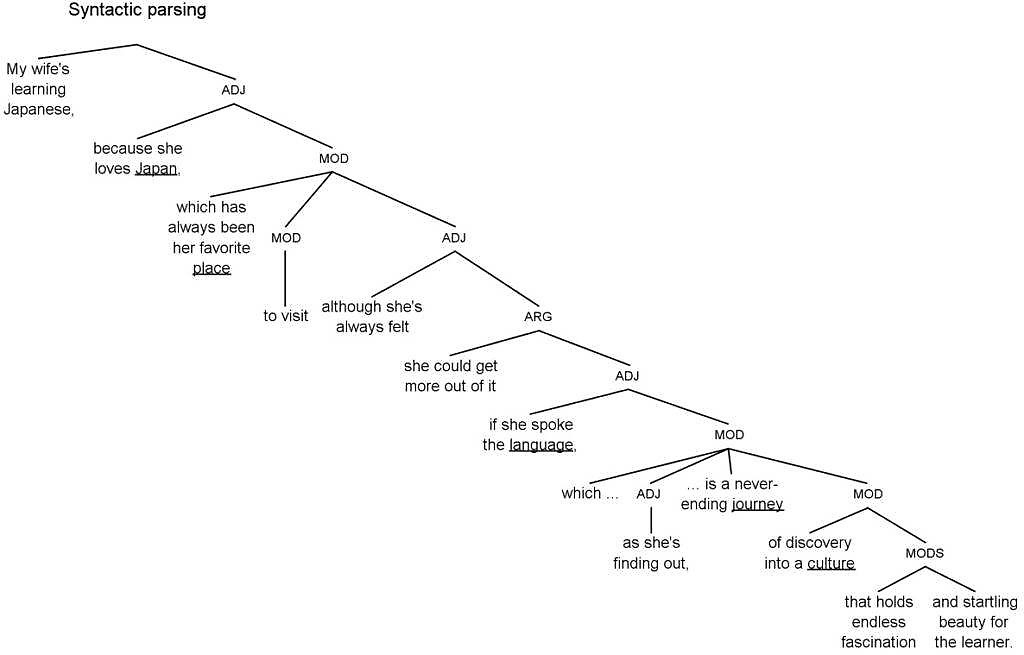

A syntactic analysis of the relations between the various parts of (142) would suggest that the sentence is mainly about the first assertion, that the speaker’s wife is learning Japanese, as illustrated in figure 92.

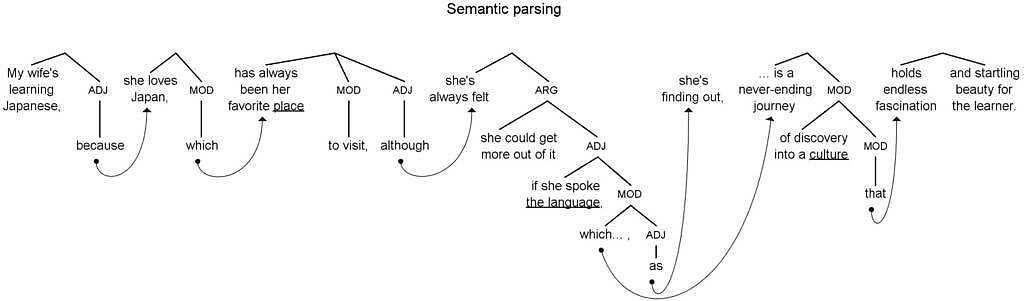

Syntactic parsing of complex sentence, suggesting prominence of main clause

But this study sees the semantic relations between propositions as more accurately reflected in a dynamic view, as illustrated in figure 93. Again, each link to a subordinate clause is shown on a separate leaf at a lower level of the tree. Most clauses are then shown as moving up to the top level of the tree, to indicate that they’re assertions and can be seen as functionally independent propositions.

Semantic parsing of complex sentence showing shifting focus of attention

3.2 Examples from the corpus

Let’s see some examples of shifting focus of attention, with clauses that are introduced as syntactically subordinate and go on to be functionally independent, in sentences from the corpus for this study. The following examples are again taken from President Obama’s 2015 speech to the UN General Assembly.

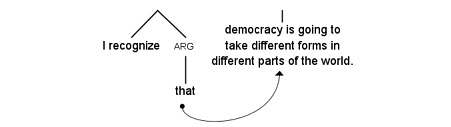

One type of sentence with shifting focus involves an assertion in a complement clause. In section 2 of this annex we saw an example of such a sentence, reproduced in (144).

(144) I recognize that democracy is going to take different forms in different parts of the world.

Based on evidence from tests of assertive force, we concluded before that each of the two clauses in (144) could be taken as an assertion in its own right. This means seeing the focus of attention as shifting as the sentence moves forward. This analysis is illustrated in figure 94.

Figure 94

Focus shifting onto assertion in a complement clause

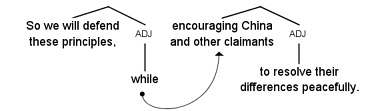

Another type of sentence with shifting focus involves an assertion in an adjunct clause, as illustrated in figure 95. The adjunct clause can be finite or non-finite.

Figure 95

Focus shifting onto assertion in an adjunct clause

The second clause in figure 95 is a non-finite clause. But it can still be taken as a functionally independent assertion about what the US administration will encourage other countries to do.

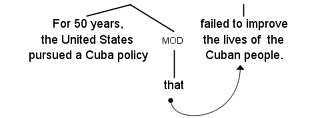

The focus of attention in a sentence can also shift onto an assertion in a relative clause, as illustrated in figure 96.

Figure 96

Focus shifting onto assertion in a relative clause

The second clause in figure 96 is a subordinate clause introduced by the relative pronoun “that.” But it can still be taken as a functionally independent assertion about the effect of the US Cuba policy.

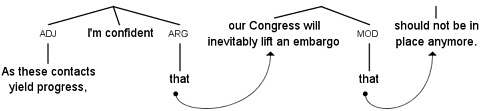

More than one type of shifting focus can occur in the same sentence, as illustrated in figure 97.

Figure 97

Multiple shifting focus

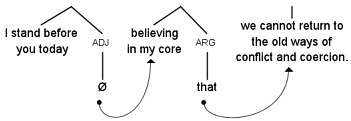

Sometimes the main clause of a sentence gives little information, but sets the context for an assertion in a subordinate clause, as illustrated in figure 98.

Figure 98

Main clause giving little information

The sentence in figure 98 is an assertion of the President’s core belief and of the impossibility of returning to the old ways, much more than of where and when he’s standing. In such cases, this study still treats the first subordinate clause as an assertion in its own right, despite its non-finite form.

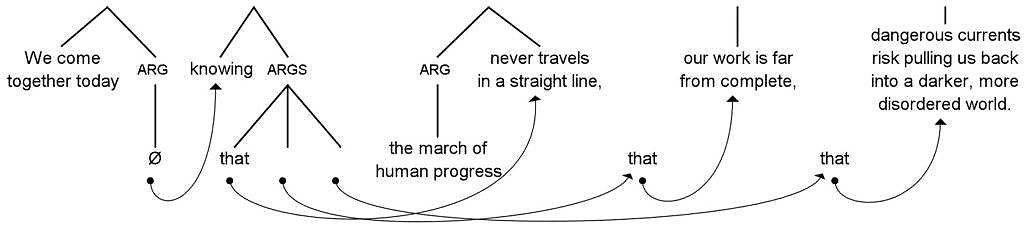

A sentence can be structured as a main clause syntactically subordinating several clauses, with the focus of attention shifting progressively from one of those subordinate clauses to the next, as illustrated in figure 99.

Figure 99

Focus of attention shifting from one subordinate clause to the next

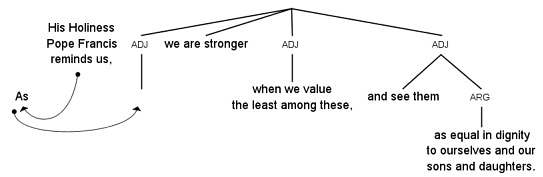

The examples in figures 94-99 show how a clause introduced as syntactically subordinate can go on to be functionally independent. But the reverse can happen too. A functionally independent clause can be syntactically subordinated to a following clause, as illustrated in figure 100.

Figure 100

Functionally independent clause syntactically subordinated to the following clause

The first clause in figure 100 can be taken as an assertion in its own right of what the Pope says. This interpretation is supported by the fact that that clause can be restated as syntactically independent, as in (145) or in (146).

(145) His Holiness Pope Francis reminds us that we are stronger […].

(146) We are stronger […], and His Holiness Pope Francis reminds us of that.

Figure 100 illustrates a functionally independent clause syntactically subordinated to a following clause. In European languages, shifts of focus in this direction are largely restricted to cases where the first clause is an adjunct to its parent. That’s because of the branching direction of complex sentence structure in European languages, where an adverbial clause can precede its parent (as in figure 100) or follow it. In contrast, a relative clause or a complement clause typically follows its parent.

One reason for this greater flexibility in position for adverbial clauses than for other types of subordinate clause may have to do with the way they attach to their parents syntactically. A complement clause attaches syntactically to a predicate in its parent, and a relative clause attaches to an argument of that predicate. In contrast, an adverbial clause attaches at a higher level, to a constituent consisting of the head of its parent clause plus any complement(s), in what’s known as an “X‑bar” relation. In any event, the most common direction of shifting focus in a European language is for a clause introduced as syntactically subordinate to go on to be functionally independent.

In Sinitic languages like Mandarin, the branching direction of complex sentence structure is more mixed, with an adverbial clause or a relative clause typically preceding its parent, whereas a complement clause typically follows its parent. And in a largely left‑branching language like Japanese, Korean or Turkish, adverbial, relative and complement clauses all typically precede their parents. In such languages, the most common direction of shifting focus is for a functionally independent clause to be syntactically subordinated to a following clause. However, this phenomenon may be more restricted in left-branching languages than the corresponding one in right-branching languages, because of factors like syntactic nesting and grammatical deranking (discussed below).

The semantic parsing model used in this study can see a syntactically subordinate clause as going on to be functionally independent, or a functionally independent clause as being syntactically subordinated to a following clause. That’s useful for our analysis of functional equivalence between the original version of a sentence and a translated or interpreted version. Ideally, the status of a proposition as functionally independent or subordinate should be preserved in translation or interpretation, even if that status is syntactically established in different ways in each version. Translation or interpretation of a complex sentence based on a syntactic analysis of its structure can lead to a loss of semantic coherence, by failing to reproduce the shifts in focus from one proposition to the next.

3.3 Deranking

European languages can be flexible in allowing subordinate clauses to be functionally independent, as described above. One reason for this flexibility is that many subordinate clauses in European languages – whether relative, complement or adjectival – retain key features of a main clause, such as a finite verb form and tense. The only thing that distinguishes such a subordinate clause from a main clause is that it may be headed by a complementizer (like “that,” “for … to” or “whether”), or that an argument may be replaced by a relative pronoun moved to the beginning of the clause. This similarity in form between a main and a subordinate clause makes it easy for a clause introduced as syntactically subordinate to go on to be functionally independent. Examples are shown in (147)-(149), along with tag questions which confirm that the subordinate clauses can be taken as functionally independent assertions.

(147) Your teacher says you’ve been skiving off again. [haven’t you?]

(148) He’s put all his stories in a book, which he’s planning to have published. [isn’t he?]

(149) My wife’s learning Japanese, because she loves Japan. [doesn’t she?]

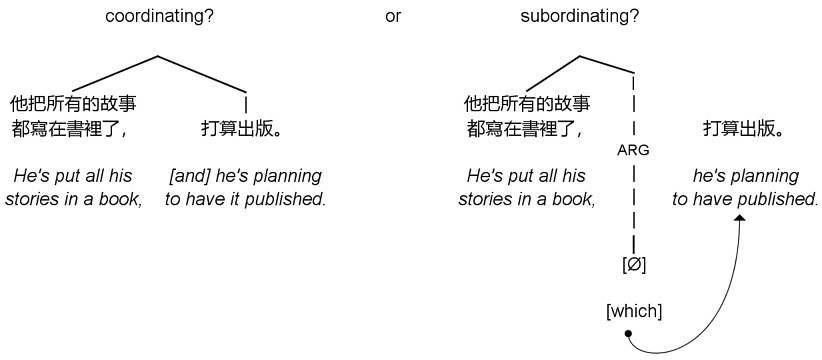

If a subordinate clause can turn out to be functionally independent in a European language, that’s even more the case in a Sinitic language like Mandarin. That’s because clause links (like many grammatical relations) in such languages are often covert, so they can be seen ambiguously as syntactic coordinators or subordinators. An example is shown in (150).

(150) 他 把 所有的 故事 都 寫 在 書 裏 了, 打算 出版。

Tā bǎ suǒyǒude gùshi dōu xiě zài shū lǐ le, dǎsuàn chūbǎn.

He obj all story all write in book inside perf, plan publish.

He’s put all his stories in a book, and is planning to have it/them published. [isn’t he?]

or: He’s put all his stories in a book, which he’s planning to have published. [isn’t he?]

This syntactic ambiguity is illustrated in figure 101.

Coordinate clause or subordinate clause

which goes on to be functionally independent in Mandarin

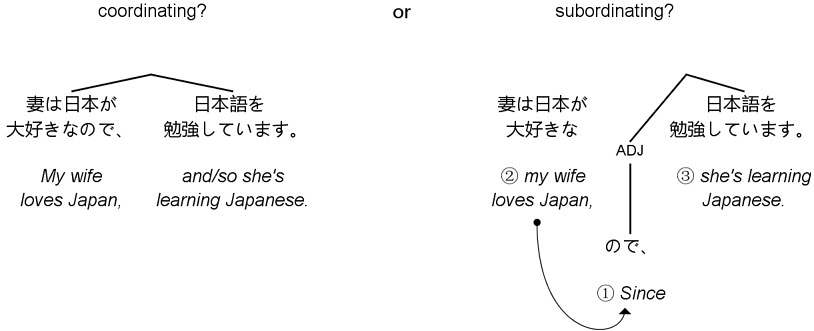

Similar ambiguity of syntactically coordinating or subordinating function can also be seen in Japanese clause chains. An example is shown in (151).

(151) 妻は 日本が 大好きな ので、 日本語を 勉強しています。

Tsuma-wa Nihon-ga daisuki-na no-de, Nihongo-o benkyou-shiteimasu.

Wife-top Japan-subj please greatly and/so/since Japanese-obj is learning.

My wife loves Japan, and/so she’s learning Japanese.

or: Since my wife loves Japan, she’s learning Japanese.

This syntactic ambiguity is illustrated in figure 102. The numbers on the second tree show the order the branches need to be read in to make sense in English.

Coordinate clause or functionally independent clause

which goes on to be syntactically subordinate in Japanese

The difference between the Japanese example in figure 102 and the English and Mandarin ones in figures 94-99 and 101 is that the Japanese link, if seen as a syntactic subordinator, works the opposite way. It takes a clause that was functionally independent – “my wife loves Japan” – and makes it syntactically subordinate to the following clause – “she’s learning Japanese.” In the Japanese sentence in figure 102, the first clause can be seen as either main or subordinate. That’s because it retains the key features of a main clause, with the exception of being headed by a final (coordinating or subordinating) conjunction.

In some languages, such shift of focus is harder to achieve, as subordinate clauses tend to be grammatically deranked. That is, they’re often formed in various ways to reflect their subordinate, background, non‑assertive function. Bril (2010) discusses the phenomenon of deranked subordinate clauses in various languages, including the use of participles and other non-finite verb forms, as well as nominalized verb forms with adpositions and case markers. Dependent events can sometimes be expressed in non-finite or nominalized forms in European languages too. But in other languages, deranking for subordinate clauses is the rule.

This is true to some extent in Japanese, where verb forms in subordinate clauses may be deranked for politeness and topic markers may be absent. It’s even more the case in Turkish, where most verb forms in subordinate clauses are deranked for tense and converted into nominal or adjectival forms, with subjects expressed as possessors. Examples are shown in (152)-(154), including literal English translations and proper English equivalents for comparison.

(152) Öğretmenin, yine okulu astığını söylüyor.

Your teacher says [lit.] “your skiving off again.” [possessive nominal]

cf. Your teacher says you’ve been skiving off again. [finite verb]

(153) Bütün hikâyelerini, yayımlatmayı düşündüğü bir kitapta topladı.

He’s put all his stories in a book [lit.] “his planning to have published.” [possessive participle]

cf. He’s put all his stories in a book, which he’s planning to have published. [finite verb]

(154) Karım Japonya’yı çok sevdiği için Japonca öğreniyor.

My wife’s learning Japanese [lit.] “because of her loving Japan.” [possessive nominal]

cf. My wife’s learning Japanese, because she loves Japan. [finite verb]

It may be possible to perceive a grammatically deranked clause in a language like Japanese or Turkish as an assertion. But that can be a lot harder than with a verb form that could appear in a main clause. That’s because a deranked clause doesn’t contain a string that can be directly taken as an assertion, negated or questioned. So it requires some mental reconstruction, including presumption of features such as tense and arguments, for the listener or reader to figure out what’s being asserted.

The subordinate clauses in the Turkish sentences in (152)-(154) are deranked not only grammatically, but syntactically too. Each of those clauses is nested, syntactically splitting the predicate and arguments of its parent. Subordinate clauses can often be both grammatically deranked and syntactically nested in a language like Japanese or Turkish. Both these features can make such clauses harder to perceive as functionally independent than would be the case in a European language. So a syntactically accurate written translation of a complex sentence from a European language into a language like Japanese or Turkish can fail to reproduce the multiple assertions the original was perceived as making, resulting in a sentence where there appears to be only one main assertion.

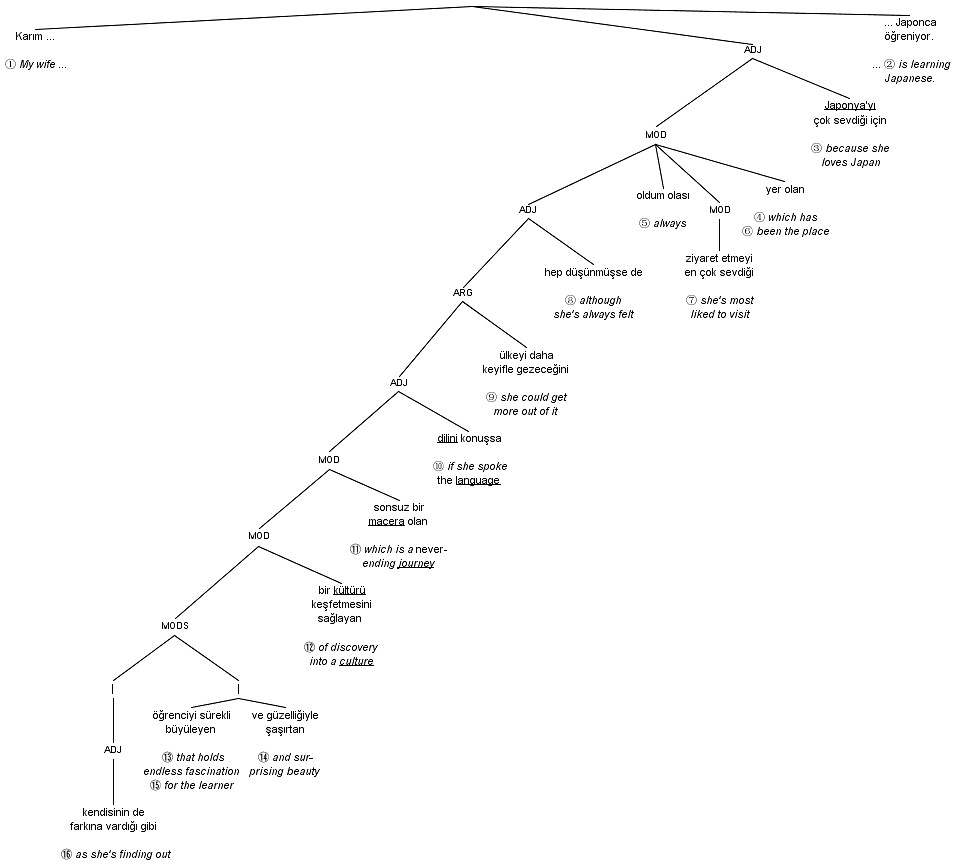

To illustrate this, let’s revisit the hypothetical run-on English sentence we saw above about the speaker’s wife learning Japanese. That sentence is reproduced in (155).

(155) My wife’s learning Japanese, because she loves Japan, which has always been her favorite place to visit, although she’s always felt she could get more out of it if she spoke the language, which, as she’s finding out, is a never-ending journey of discovery into a culture that holds endless fascination and startling beauty for the learner.

If we try to translate the sentence in (155) into a language like Japanese or Turkish by copying the syntactic structure of the English original, as a single sentence with one main clause and several subordinate clauses, the subordinate clauses are likely to be grammatically deranked. To show the problems this can create, a parse tree with a syntactically accurate Turkish translation of (155) can be seen in figure 103. The numbers show the order the branches need to be read in to make sense in English.

Syntactically accurate Turkish translation of complex sentence

Each of the clauses in the syntactically accurate translation in figure 103 is rendered nicely and idiomatically in Turkish. But the overall effect may be disturbing, for a number of reasons. The first reason is the big gap at the top level of the tree between the subject and predicate of the single syntactic main clause. Such dependency gaps can often occur in translation between languages with very different structure, as we saw in section 3.3.3 on nested structures. A second problem with the Turkish translation in figure 103 is that it doesn’t recreate all the semantically flexible links which appeared in the original English version in (155). Instead, the translation reflects an analysis of the syntactically subordinate clauses as being functionally subordinate as well, because they have deranked verb forms and are nested within the single syntactic main clause.

Like subordinate status, assertive status is relative and can be hard to pin down. As explained above, the fact that the subordinate clauses in figure 103 are grammatically deranked makes it impossible to apply any empirical assertion test to them, like a tag question or a negation test. That suggests that their assertive force is weakened.

A third problem with the translation in figure 103 is the order in which the assertions – to the extent that they’re seen as assertions in their weakened form – are presented. This problem is discussed in the section on logical order in the epilogue, which suggests an alternative translation to solve these problems.

We now have a semantic, functional method for analyzing complex sentence structure, which reflects the view that the focus of attention in a complex sentence can shift as the sentence moves forward. In a complex sentence with no nestings, each proposition can generally be processed before or as soon as the next one begins. Our model also sees many syntactically subordinate clauses as being functionally independent, rather than positing a complex hierarchical structure with multiple layers of subordination. That means that logical windows for processing propositions are generally seen here as successively opening and closing, without ever getting too big or too deep.

This section has illustrated various aspects of the semantic parsing model used in this study. The model doesn’t ensure black-and-white parsing decisions for every sentence. But it’s fit for its purpose – as a technical tool for comparing original and translated or interpreted versions of complex sentences in terms of the linear order of propositions and the hierarchical relations between them. The guidelines for using that tool are summarized in the next section.

→ 4. Parsing guidelines