Annex I – Semantic parsing

1. Propositions

1.1 Predicate-argument structure

Lyons (1995) sees propositions expressed in different syntactic forms as equivalent if they meet the same truth conditions. This study applies that notion of semantic equivalence to propositions establishing similar logical relations among similar entities as expressed in different languages. Propositions are displayed here in their surface syntactic forms, rather than being analyzed in terms of their truth value. The method used mirrors the traditional three-way syntactic classification of a subordinate clause as a relative, complement or adverbial clause – that is, as an argument, modifier or adjunct in relation to its parent. But it applies that classification to the semantic relations between propositions. Accordingly, each functionally subordinate proposition is labelled as a semantic argument, modifier or adjunct in relation to its parent. There’s also a fourth label used, for a proposition expressing reported speech or thought.

This study differs from many analyses of propositions in a few respects. First, it operates on a larger scale, examining the relations between propositions rather than their internal logical content. Second, it defines “proposition” in a broader sense, including closed propositions (expressed in a finite clause, with the tense and all arguments specified or implied), as well as open propositions (expressed in a non-finite clause or nominal structure, with the tense or at least one argument missing). Third, the term “proposition” is used here to refer not only to an underlying semantic function, but also to any predicate-argument structure giving syntactic expression to a proposition. In these respects, this study uses the term in the same way as Larson (1984), who uses the proposition as a unit of analysis to examine the preservation of meaning in translation.

Let’s take a look at the various syntactic forms which can be used to express propositions, and at the semantic relations between them. Syntactically, an event or situation can be described in a finite clause, a non-finite clause or a clause-like nominal structure.

A finite clause is a clause where the tense and all the arguments are known, as in (25).

(25) I love you.

A non‑finite clause is a clause where the tense or at least one argument is unknown, as in (26) and (27).

(26) my loving you (no tense)

(27) loving you (no tense, one argument missing)

A clause-like nominal structure is a noun phrase derived from an underlying clause and expressing the same semantic relations between a predicate and its arguments, as in (28).

(28) my love for you

Each description of an event or situation is built around a semantic predicate, as highlighted in (29).

(29) I love you.

A predicate is the linguistic expression of a logical function. (“Predicate” is used here in this modern linguistic sense, not as in traditional grammar, meaning the part of a clause which is left when the subject is removed.) A predicate takes one or more entities as input values and yields an actual or potential truth value as an output. (The perspective and criteria for assessing truth values aren’t relevant here.) Such a logical function can be represented as in (30).

(30) love (I, you) = {true} or {false}

The input values of a logical function – the entities involved in the event or situation it describes – are semantic arguments, as highlighted in (31).

(31) I love you.

Any modifiers of the predicate are adjuncts, as highlighted in (32).

(32) I truly love you.

A semantic predicate can appear syntactically as various parts of speech, as shown in (33)-(36).

(33) I know. (verb)

(34) She’s an expert. (noun)

(35) I’m interested. (adjective)

(36) We’re inside. (preposition)

The word “inside” in (36) would be called an “adverbial particle” in traditional grammar. But it can also be seen as an intransitive preposition – that is, a prepositional predicate without a complement.

The idea of some prepositional phrases having internal argument structure, with the preposition functioning as a predicate, is well established in modern syntactic theory. Jackendoff (1973: 347), Emonds (1985: 253), Huddleston and Pullum (2002: 600) and others discuss the distinction between a transitive preposition, which takes a complement, and an intransitive preposition, which has no complement. Grimshaw and Williams (1993) distinguish between a “semantic” preposition, which acts as a predicate, and a “grammatical” preposition, which doesn’t. Merlo and Ferrer (2006: 347) use various tests to determine when a preposition predicates a separate property of its head. Such descriptions of the internal argument structure of some prepositional phrases can also be applied to some postpositional phrases (in languages with postpositions) and to some case phrases (in languages with case).

In some languages, like English, a finite clause needs a verb. So a predicate other than a verb in a finite clause is linked to its subject by a semantically empty verb, like “be.” The various forms of “be” in (34)-(36) are examples.

The predicates highlighted in (33)-(36) are intransitive, taking no complement. All these types of predicate can also be transitive, taking a complement in addition to the subject, as in (37)‑(40).

(37) I know Japanese.

(38) She’s an expert at show-jumping.

(39) I’m interested in linguistics.

(40) We’re inside the haunted house.

Many of these relations can also be expressed in nominal structures, as in (41)-(43).

(41) my knowledge of Japanese

(42) her expertise at show-jumping

(43) my interest in linguistics

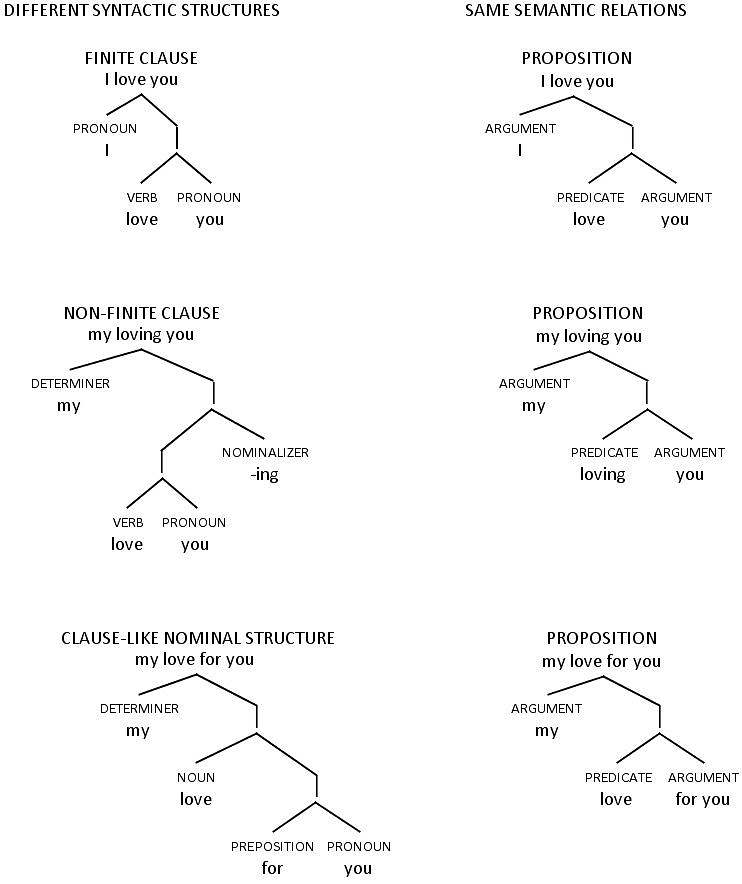

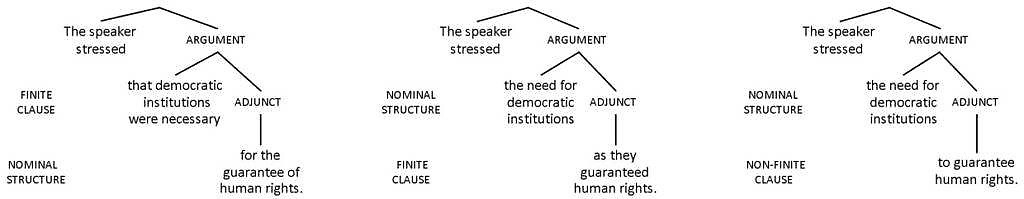

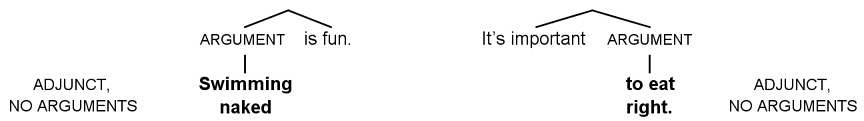

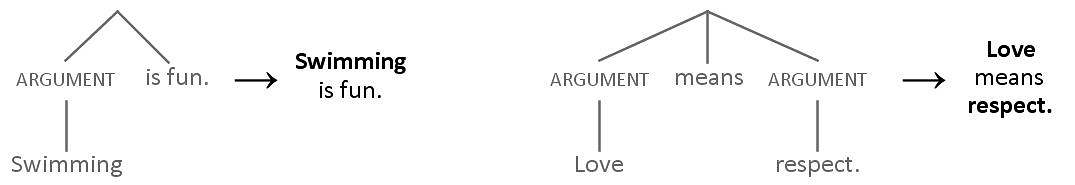

Propositions like (41)-(43) are referred to in this study as “clause-like nominal structures.” A finite clause, a non-finite clause and a clause-like nominal structure can all express the same semantic relations between a predicate and its arguments, even though their syntactic structures are different, as illustrated in figure 61.

Figure 61

Different syntactic structures expressing the same semantic relations

A syntactic construction which describes an event or situation by establishing logical relations between a predicate and its arguments is a predicate-argument structure. This study uses the term “proposition” to refer to any such construction.

1.2 Relations between propositions

[This sub-section is included in the summary of the semantic parsing method in chapter 3, section 3.1.2. The figures are renumbered here.]

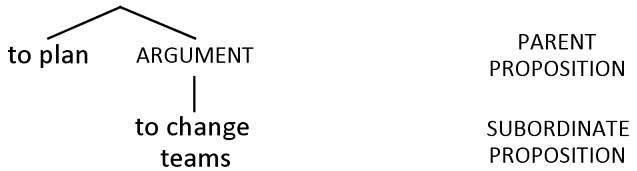

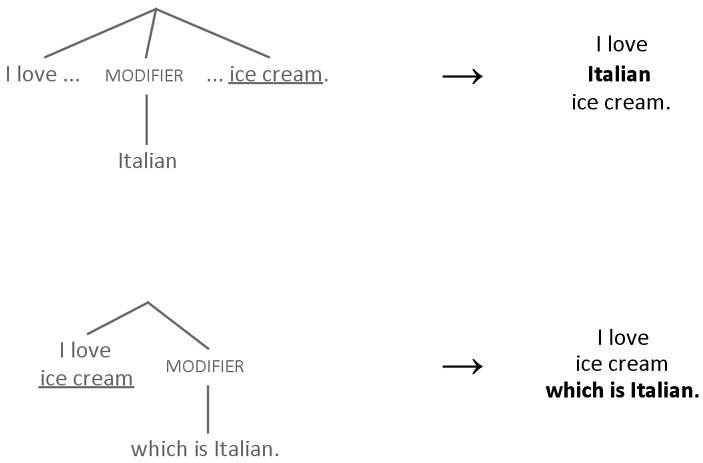

One proposition can be subordinate to another, parent proposition, as illustrated in figure 62.

Figure 62

Parent and subordinate propositions

Each of the propositions in figure 62 can be expressed as a clause or as a clause-like nominal structure. The relations of semantic hierarchy between predicates and arguments in figure 63 are the same.

spacer

Figure 63

Parent and subordinate propositions with the same hierarchical relations

For simplicity and clarity, the parse trees used here include an overt link between propositions on the same branch as one of the propositions. If one proposition is subordinate to another, an overt link between them – like “for” in the last tree in figure 63 – is included on the same branch as the subordinate proposition.

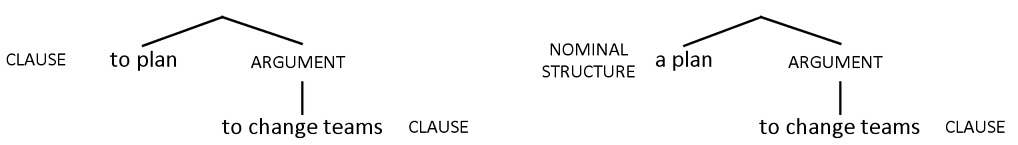

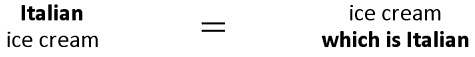

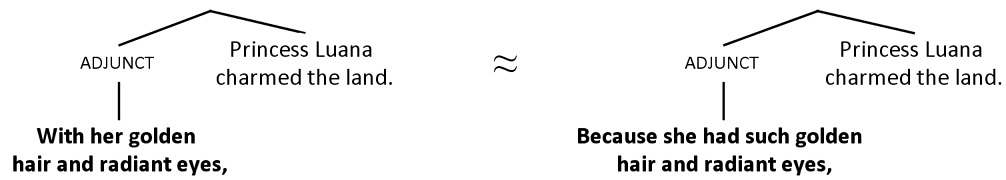

The relations between a parent and a subordinate proposition can sometimes be recast with minimal differences in meaning from one syntactic form to another, as illustrated in figure 64.

Figure 64

Propositions with similar hierarchical relations

This kind of switch is possible within a language, as in the examples in figures 63 and 64. It’s also possible in translating or interpreting a message from one language to another. A method of analysis based on propositions, where clause-like nominal structures are treated in the same way as finite and non‑finite clauses, reflects the semantic similarities between the different syntactic forms which various languages can use to describe an event or situation. It also helps highlight whether the hierarchical relations between propositions, whatever their syntactic form, are preserved in translation or interpretation.

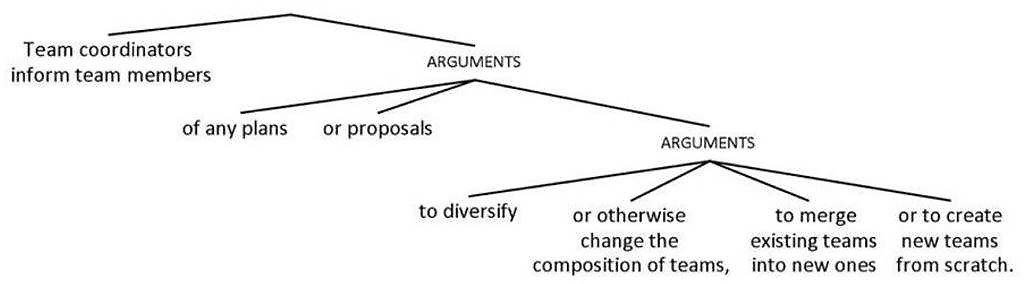

Figure 65 shows a parse tree of the hierarchical relations between propositions in a complex sentence. The labels on the nodes indicate the semantic role of each subordinate proposition in relation to its parent. In this sentence, each subordinate proposition is a semantic argument of its parent.

Semantic parse tree of complex sentence

In the parse tree in figure 65, the propositions in the bottom row function as arguments of the underlying verbs “plan” and “propose,” from which the nominal predicates in the second row are derived. “Plans” and “proposals” are treated here as process nominals – that is, predicates with argument structure. In contrast, “composition” in the second proposition in the bottom row is treated as a result nominal with no argument structure – just as if it said “names” or “numbers” instead of “composition.” The distinction between result nominals and process nominals is sometimes fuzzy. This distinction is discussed below, in section 1.7 of this annex.

The sort of semantic parse tree used here is similar in appearance to syntactic parse trees in the tradition of generative grammar. The main difference is that each leaf on the trees used here shows the syntactic expression of a semantic proposition. This method of segmentation and display allows for one‑to-one comparison of corresponding propositions in translation and interpretation, however they’re expressed in different languages. It also helps illustrate problems in transferring complex sentence structure from one language to another.

1.3 Closed and open propositions

A clause-like nominal structure is unspecified for tense, as in (44).

(44) children’s respect for teachers

nominal structure

tense unspecified

A corresponding finite clause would require the tense to be specified or implied, as in (45).

(45) Children respect teachers.

finite clause

tense specified

A clause-like nominal structure can also have undefined arguments, while a corresponding finite clause would require all arguments to be defined. For example, the predicate [respect] is a binary function. It takes two arguments as inputs, and returns a truth value – true or false – as an output, as shown in (46).

(46) Children respect teachers.

respect (children, teachers) = {T, F}

Here both arguments are defined by known values – “children” and “teachers.” A proposition whose arguments are defined by known values and where tense is specified or implied is a complete or closed proposition. Such a proposition returns an actual truth value – true or false. (Again, the perspective and criteria for determining that value are irrelevant here.)

The predicate [respect], expressed as a noun, shares the argument structure of the verb it’s derived from. But a proposition expressed with the nominal form of the predicate may have an undefined argument, as in (47).

(47) respect for teachers

nominal structure

one argument undefined

A corresponding finite clause would require all arguments to be defined, as shown by the incompleteness of (48).

(48) *respect teachers

finite clause

needs another argument

A predicate with one or more undefined arguments or unspecified for tense is an incomplete proposition. Such a proposition returns a potential truth value, rather than an actual one. This type of proposition can be called a “propositional function,” in the tradition of Russell (1903) and Lewis (1918). Cresswell (1973) and others use the term “open proposition,” by analogy to what Quine (1986) and others call an “open sentence.” This study uses the term “proposition” for any predicate with at least one argument or adjunct, including open propositions as defined here.

A proposition with the same nominal predicate as in (47), but with a different undefined argument than in (48), is shown in (49).

(49) children’s respect

nominal structure

one argument undefined

A corresponding clause would again need all arguments to be specified, as shown by the incompleteness of (50):

(50) *children respect

finite clause

needs another argument

There’s no black-and-white rule for what constitutes the syntactic expression of a proposition. Rather, there’s a continuum of predicate-argument structures in various languages expressing propositions, as defined broadly here. Ranging from fully fledged propositions to trivial ones, these include:

• finite clauses, as in figure 66

Figure 66

Finite clause

• tenseless clauses with full argument structure, as in figure 67

Figure 67

Tenseless clauses with full argument structure

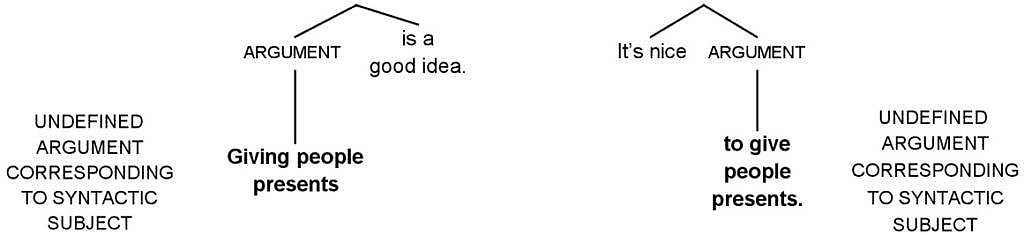

• gerund and infinitive clauses with one or more undefined arguments, as in figure 68

Figure 68

Gerund and infinitive clauses with undefined arguments

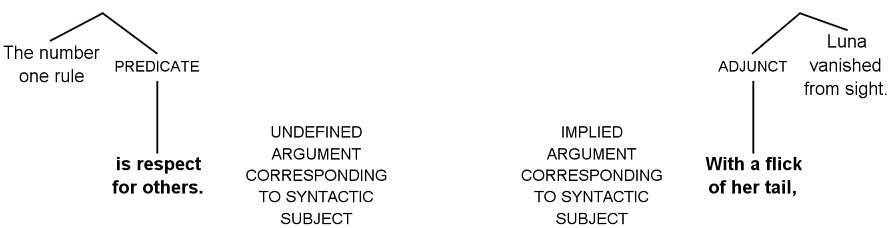

• clause-like nominal structures with one or more undefined or implied arguments, as in figure 69

Figure 69

Clause-like nominal structures with undefined or implied arguments

• gerunds and infinitives with adjuncts but no arguments, as in figure 70

Figure 70

Gerunds and infinitives with adjuncts but no arguments

• Finally, a nominal may have empty argument structure, as in figure 71.

Such nominals aren’t treated as separate propositions in this study.

Figure 71

Nominals with empty argument structure – not treated here as separate propositions

1.4 Adjuncts to predicates

Besides a predicate and its arguments, a proposition can also include other elements which modify the predicate. Those elements aren’t required inputs for the logical function to return an actual or potential truth value, though they can change the truth value returned. Such additional elements are adjuncts.

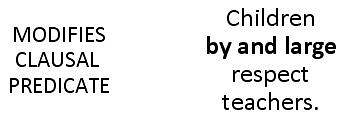

An adjunct can modify a clausal predicate, as in figure 72.

Figure 72

Adjunct to clausal predicate

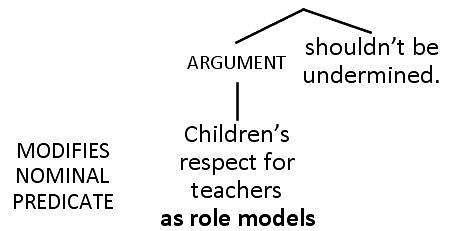

Or an adjunct can modify a nominal predicate, as in figure 73.

Figure 73

Adjunct to nominal predicate

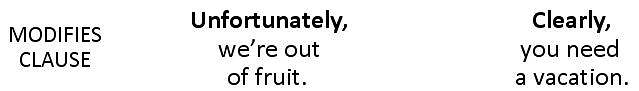

Or an adjunct can have scope over an entire clause, as in figure 74.

Figure 74

Adjuncts to entire clauses

An adjunct to a clause, like the ones highlighted in figure 74, is also called an “extra‑clausal constituent,” and is considered part of the “macro-syntax” (as opposed to the “micro-syntax”) of a sentence (Kaltenböck et al. 2016). Blanche-Benveniste (1983) calls such clauses “sentence complements” (as opposed to “verb complements”). Quirk et al. (1989) call them “disjuncts” and “conjuncts” (as opposed to “adjuncts” – a term they reserve for adjuncts to predicates). Adjuncts to clauses are treated as operators separate from discourse units in some segmentation methods, such as the linguistic discourse model (Polanyi et al. 2004).

But it can be hard to tell if an adjunct has scope over an entire clause or if it modifies the predicate of that clause. Sometimes the place of an adjunct can help determine its scope. For example, in some languages, an adjunct at the beginning of a clause can be seen as having scope over the entire clause, whereas an adjunct placed later can be seen as modifying the predicate of that clause, as in figure 75.

Figure 75

Adjuncts to clauses vs adjuncts to predicates

But this criterion may not always work. Also, the distinction is too language-specific to be used reliably in comparing different language versions of a sentence. In any case, an adjunct to a clause generally remains attached to the same clause in the translated or interpreted version of a sentence as in the original version. For all those reasons, the parsing method used here doesn’t distinguish between adjuncts to clauses and adjuncts to predicates.

1.5 Subordinate propositions

Modifying propositions

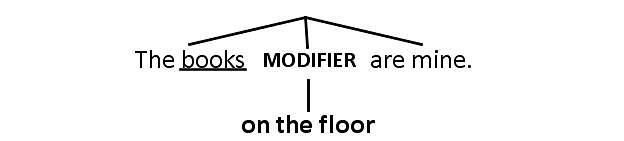

A subordinate proposition can modify a noun in a parent proposition. In figure 76, the modifier is a shortened relative clause with a prepositional predicate. (Recall that a preposition can function as a predicate, with or without a complement, as discussed in section 1.1 above.) The modified noun on the upper leaf is underlined, to show what the subordinate proposition modifies.

Figure 76

Subordinate proposition modifying a noun in its parent

Sometimes a subordinate proposition syntactically splits the predicate of a higher-level proposition from one or more of its arguments. In figure 76, the predicate and argument of the main proposition, “The books are mine,” are syntactically split by the modifying proposition, “on the floor.”

Modifying propositions include restrictive relative clauses, as in figure 77.

Figure 77

Restrictive relative clauses

Sometimes an adjective can be rephrased as a relative clause, as in figure 78.

Figure 78

Adjective rephrased as relative clause

But this study groups a modifier without arguments or adjuncts in the same proposition as the noun it modifies, as illustrated in figure 79.

Figure 79

Modifiers with no arguments or adjuncts

grouped in same propositions as modified nouns

Argument propositions

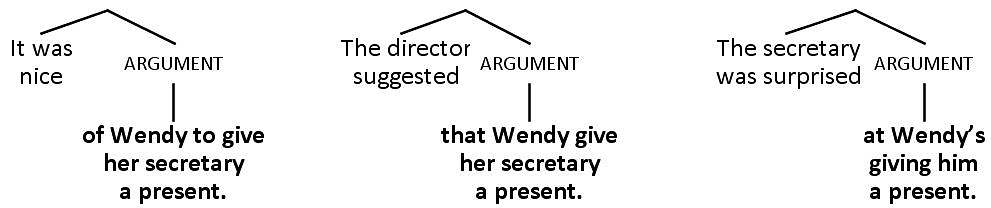

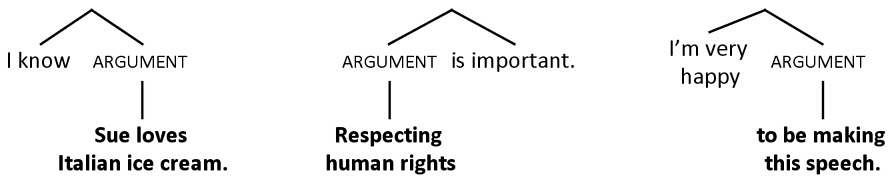

A semantic argument is the semantic equivalent of a syntactic argument (subject or complement) of a predicate. A subordinate proposition can be a semantic argument of the predicate in a parent proposition, as in figure 80.

Figure 80

Subordinate propositions as arguments of predicates in parents

Adjunct propositions

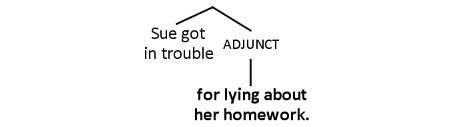

A subordinate proposition can be a semantic adjunct to the predicate in a parent proposition, as in figure 81.

Figure 81

Subordinate proposition as adjunct to predicate in parent

Some non-clausal adjuncts don’t appear to have predicate-argument structure, as they don’t have an obvious predicate. But they still act like propositions in their own right. Schauer (2000) proposes treating a phrase as a separate discourse unit if it: (a) provides information other than semantically typical information like means, place or time, and (b) can be rephrased as a clause. Larson (1984: 219-223) considers indication of agent, causer, affected entity, beneficiary, accompaniment, result, instrument, location, goal, time, manner or measure to be semantically typical information in a proposition. This study adopts a combination of those two sets of criteria for treating a non-clausal adjunct as a proposition. Specifically, a non-clausal adjunct is treated here as a proposition if it: (a) provides information other than that in Larson’s list of semantically typical information in a proposition or describes an event, and (b) can be rephrased as a clause. An example can be seen in figure 82.

Figure 82

Non-clausal adjunct treated as a proposition

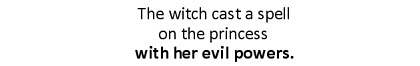

A non-clausal adjunct like the one highlighted on the left in figure 82: (a) provides semantically non-typical information, as defined (information other than agent, causer, affected entity, beneficiary, accompaniment, result, instrument, location, goal, time, manner or measure), and (b) can be rephrased as a clause. So such an adjunct is treated here as a separate proposition. In contrast, the adjunct in figure 83 provides semantically typical information (the instrument) and is not treated here as a separate proposition.

Figure 83

Adjunct not treated as a proposition

Of course, none of these tests are absolute, as the propositional status of phrases is on a continuum. That’s why it’s important for this study that any decision as to whether to assign propositional status to a given phrase in the original version of a sentence, based on criteria such as described above, should be applied consistently to all other language versions of that sentence when the meaning is judged to be the same.

Translating or interpreting a proposition from one language to another can involve changing its syntactic form from a finite clause to a non-finite clause, or from a clause to a clause-like nominal structure or a non‑clausal adjunct proposition. For optimal cross-linguistic comparison, all phrases with propositional function as described above are treated in this study as separate propositions.

1.6 Reported speech or thought

A construction expressing reported speech or thought is functionally neither independent nor subordinate in the same way as other constructions. Consider the highlighted propositions in (51)-(54).

(51) She was like, “Cool.”

(52) The teacher said: “Please arrive early tomorrow, since the buses will be leaving at 8:15.”

(53) The sign says items may be returned for a refund within 30 days if accompanied by the receipt.

(54) Commercials are so annoying. “Buy me now!” Like I really need a programmable vacuum cleaner.

Syntactically, such constructions may look like they’re in a relation of subordination. But they’re different from typical subordinate constructions in several ways. These include: (a) a shift of perspective away from the speaker or writer, (b) salience of information, (c) a wide range of complexity, (d) distinctive prosody and (e) the fact that they can appear without a syntactic parent, as in (54). Because of these cross-linguistic features, Spronck and Nikitina (2019) argue that reported speech or thought “involves a number of specific/characteristic phenomena that cannot be derived from the involvement of other syntactic structures in reported speech, such as subordination.” In addition to modifying, argument and adjunct propositions, propositions like those highlighted in (51)‑(54) are treated here as having a fourth type of semantic relation to an explicit or implied parent: reported speech or thought.

On the other hand, a statement or view which the speaker or writer identifies with isn’t treated here as reported speech or thought. Consider the highlighted propositions in (55)-(57).

(55) We all know we’re living in challenging times.

(56) The report proves that temperatures are rising.

(57) Passengers are informed that the departure gate for flight AB 105 to Seoul has changed.

Such propositions don’t shift perspective away from the speaker or writer. So they’re treated here as functionally independent propositions. Their effect is similar to the highlighted propositions in (58)-(60).

(58) We’re living in challenging times, and we know it.

(59) Temperatures are rising, and the report proves it.

(60) The departure gate for flight AB 105 to Seoul has changed, and passengers are hereby informed of

that fact.

1.7 Nominals

An area where parsing decisions are sometimes borderline is how to treat a construction headed by a nominal – an abstract noun derived from an underlying verb or adjective. The question is whether to treat such an abstract noun as a “process nominal” or a “result nominal.”

A nominal is characterized here as a “process nominal” if it describes a process, event or situation. Like its underlying verb or adjective, a process nominal can have argument structure. Examples can be seen in (61)-(66).

(61) my love for you

(62) my interest in linguistics

(63) their need for help

(64) reporting on trends

(65) the importance of change

(66) food security

A process nominal can often be rephrased as a gerund, as in (67) and (68).

(67) their efforts to help → their/them trying to help

(68) greenhouse gas emissions → the emitting of greenhouse gases

Or it can be rephrased as a clause with a complementizer (like “that” or “for … to”), as in (69) and (70).

(69) the importance of change → the fact that change is important

(70) food security → for food supplies to be secure

This study treats a process nominal as the predicate of a separate proposition if it has any arguments or adjuncts, as in (71) and (72).

(71) climate change (the changing of the climate)

(72) sustainable development (developing in a sustainable way)

Likewise, a participial modifier with any arguments or adjuncts is treated here as a separate proposition, similar to a relative clause, as in (73) and (74).

(73) a [country-driven] approach (an approach [driven by the features and needs of a country])

(74) the [rapidly changing] climate (the climate, [which is changing rapidly])

Of course, phrases like “food security,” “climate change” and “sustainable development” are more or less established terms. As such, they may be less internally processed than other constructions and may have established equivalents in other languages. But they still have argument structure, consisting of an underlying predicate (secure, change or develop) with at least one argument or adjunct. Plus, there’s no objective way to determine to what extent a nominal may be internally processed. “Climate change” is clearly an established term, so it probably wouldn’t be processed much internally. But what about a less established phrase, like “weather change” or “rapid climate change”? To what extent would such phrases be internally processed? Probably more than “climate change,” but less than “predicting the weather.” And of course it would depend on the person doing the processing and how often they’d encountered the phrase. There’s no way to measure it objectively. To avoid subjective guessing on such questions, this study treats all nominal constructions consistently in the same way. And of course, the same criterion is applied to all such constructions in each language version of a sentence. So a different decision as to whether or not to treat a given nominal as a predicate would have no effect on the comparative results between different language pairs as measured in this study.

In contrast, a nominal or abstract noun is characterized here as a “result nominal” if it describes the result of an action or something created by an action. Like any noun, a result nominal can take modifiers. But a result nominal tends to be closed to arguments (even if its modifiers could be arguments of an underlying verb or adjective). Examples can be seen in (75)-(78).

(75) my linguistic interest(s)

(76) a report on trends

(77) the effects of change

(78) support activities

Such a nominal generally can’t be rephrased as a gerund. It’s not an “-ing,” but a “thing,” as in (79) and (80).

(79) an announcement (a thing that’s announced)

(80) a report (a thing that’s written, things that are reported)

This study treats a result nominal as a simple noun, not as the predicate of a separate proposition, even if it’s modified. Examples can be seen in (81) and (82).

(81) common responsibilities

(82) respective capacities

Several researchers (Melloni 2011; Alexiadou 2010; Rozwadowska 2017; Grimshaw 1992) discuss the distinction between process and result nominals. The distinction isn’t always clear-cut, as in (83) and (84).

(83) greenhouse gas emissions = the process of emitting greenhouse gases?

or the gases that are emitted?

(84) their progress towards the goal = the process of their progressing toward the goal?

or the results they’ve achieved?

Sometimes the form of a nominal in one language suggests a reading as a process nominal, while its form in another language suggests a reading as a result nominal. For example, the standard Turkish term for “climate change” (iklim değişikliği) suggests that it refers to a change that’s been produced in the climate, whereas the term used in most other languages is likely to be seen as referring to the process of the climate changing.

To minimize the effect of such differences on our data, care has been taken here to consistently parse each nominal in a translated or interpreted version of a sentence in the same way as in the original English version, whenever the information content is judged to be the same.

We’ve seen how this study uses the proposition as a unit of analysis. Now let’s take a closer look at the parsing method used here to segment sentences into propositions and to indicate the hierarchical relations between them.

← Annex I – Semantic parsing