Annex I – Semantic parsing

2. A functional approach

The method of parsing complex sentences used in this study is described as “semantic” and “functional.” That’s because it parses complex sentences into semantic propositions, as was explained in section 1 of this annex, and is based on underlying semantic function rather than surface syntactic form.

We’ve seen how a semantic parse tree, similar to a syntactic parse tree in the tradition of generative grammar, can be used to illustrate the propositional structure of a complex sentence. Here’s more detail on how the parse trees in this study are laid out: Though segmented semantically, propositions are displayed as leaves on the trees in their surface syntactic forms. Some features recorded for our statistical analysis involve the linear order of propositions in a complex sentence. So the parse trees are spread out horizontally to show both the linear order of propositions and the hierarchical relations between them.

Syntactically contiguous parts of a proposition are shown together on the same leaf of a tree. A functionally independent proposition – one which makes an assertion – is shown at the top level of the tree. A functionally subordinate proposition, including one which is part of a parent proposition, is shown at a lower level. Parts of a proposition which are syntactically split by another proposition are shown on separate leaves, at the same level and under the same node. An overt coordinating link between propositions is included on the same leaf as one of the linked propositions. An overt subordinating link is included on the same leaf as the subordinate proposition.

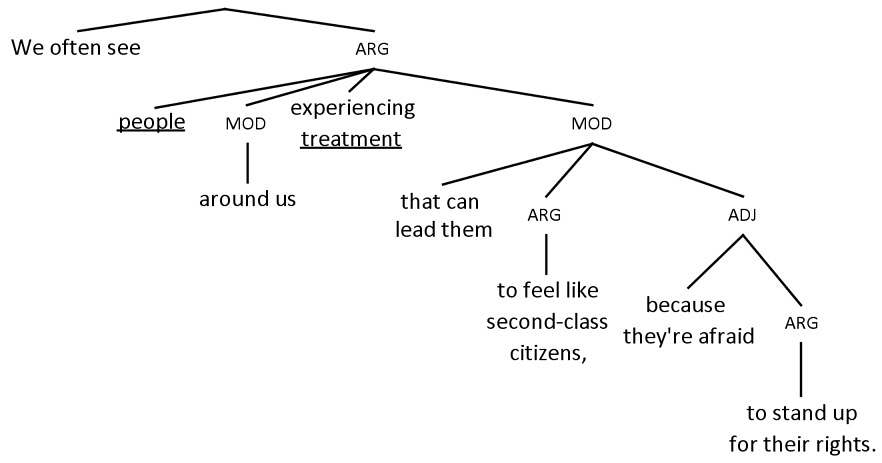

Each subordinate proposition is labeled arg (argument), mod (modifier) or adj (adjunct) in relation to its parent. A proposition containing reported speech or thought is labeled rep. The label for a subordinate or reported proposition is shown at the same level and under the same node as its parent. (For a reported proposition, the parent is the proposition where the perspective of the reported one is established.) A noun modified by a subordinate proposition is underlined. An example semantic parse tree of a complex sentence is shown in figure 84.

Figure 84

Semantic parse tree of a complex sentence

2.1 Not all propositions are clauses

The semantic, functional approach to complex sentence analysis used here is similar in many ways to Cristofaro’s (2003) analysis of subordination, in that it focuses on underlying meaning rather than syntactic form. Instead of the traditional unit of analysis for complex sentences, the syntactic clause, Cristofaro uses the state of affairs – the description of an event or situation. That’s a lot like the unit of analysis in this study – the proposition.

Cristofaro’s (2003: 2) functional approach defines a pair of linked clauses as being in an asymmetric relation if one clause describes an event or situation which “lacks an autonomous profile, and is construed in the perspective of the other event (which will be called the main event).” In a sentence with two asymmetrically linked clauses, there’s generally a main event or situation description, which is an assertion, and a subordinate description, which provides assumed or background information.

Cristofaro proposes three types of test – sentence negation, sentence questioning and tag questions – to determine whether a clause in a complex sentence is an assertion. Accordingly, she classifies that clause as functionally independent or subordinate. English tag questions (like “has she?” or “wouldn’t they?”) are handy for this purpose, as they reflect the person and tense of the verb in the clause being questioned. Cristofaro uses English tag questions – on original English sentences and on translations of sentences from other languages – to test which of two linked clauses is functionally independent and which is subordinate. For example, consider (85).

(85) He thinks it will rain.

If we add a tag question to (85), we get (86).

(86) He thinks it will rain, doesn’t he?

(= Isn’t it true that he thinks that?)

We don’t get (87).

(87) *He thinks it will rain, won’t it?

(≠ Isn’t it true that it will rain?)

As shown in (86), the main clause in (85), “He thinks,” can be questioned with a tag question, indicating that it’s an assertion. As shown in (87), the subordinate clause in (85), “it will rain,” can’t be questioned with a tag question, indicating that it’s not an assertion. That second clause is functionally subordinate to the main clause, “He thinks.”

Cristofaro gets close to a definition based on semantic propositions as used here, saying that her analysis is based on “functional relations” between states of affairs, “rather than any formal feature of specific clauses” (2003: 51). But the phrase types she applies her assertion tests to and characterizes as independent or subordinate are all finite or non‑finite clauses. Her states of affairs don’t seem to cover other syntactic structures that can express propositions as perceived in this study.

Such structures include clause-like nominal structures, as in (88).

(88) I must confess my love for you.

They include shortened relative clauses, as in (89).

(89) The papers on the desk are mine.

They also include other phrases with propositional function, as in (90).

(90) We’ll get there in time thanks to your help.

Cristofaro gives a few examples of states of affairs expressed in clauses with nominalized verb forms, as in the Finnish sentence in (91).

(91) Huomaan pojan osanneen suomea.

literally: “I realized the boy’s knowing Finnish.”

= I realized that the boy knew Finnish.

But her analysis of subordination doesn’t seem to include events described in functionally similar clause-like nominal structures, as in (92).

(92) I admired the boy’s knowledge of Finnish.

Like Larson (1984), the method used here treats all phrases with predicate-argument structure as propositions, including ones like those highlighted in (88)-(90) and (92).

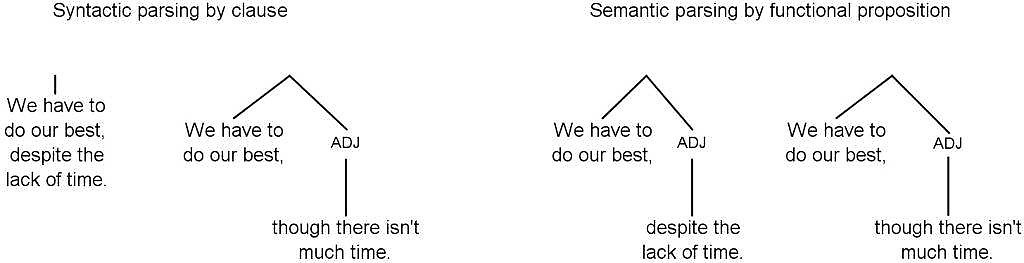

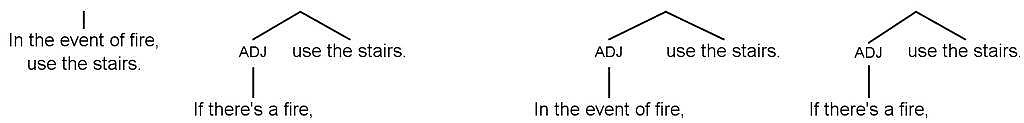

Using the proposition as a unit of analysis can lead to more unit divisions than using the clause, with a phrase like “thanks to your help” being treated as a functional proposition. As explained in section 1.5 of this annex, a non-clausal adjunct is treated here as a proposition if it (a) provides information other than agent, causer, affected entity, beneficiary, accompaniment, result, instrument, location, goal, time, manner or measure or describes an event, and (b) can be paraphrased as a clause. Some more examples are illustrated in figure 85.

Figure 85

Syntactic vs semantic parsing of non-clausal propositions

Cosme (2008: 91) observes: “What is expressed by a phrase in one language may be expressed by a clause in another language…. Translating from English into German frequently triggers … a phenomenon whereby a clause in the source language is turned into a phrase in the target language.” Doherty (1999: 115) gives examples of this phenomenon in German-to-English translation, as in (93).

(93) Auch werden bei einem verlangsamten Zellwachstum nur geringe Mengen an natürlichem

Interferon gefunden.

(literally: “Also with slowed-down cell growth, only small amounts of naturally produced

interferon are found.”)

→ Also when cell growth is slowing down, only small amounts of naturally produced interferon

are found.

This functional equivalence of different syntactic structures used to express propositions is key to the way proposed here for assessing complex sentence transfer between languages. Like Larson (1984), this study sees reproduction of the hierarchical relations between all propositions, regardless of syntactic form, as central to preserving meaning in a successful translation.

2.2 Not all clauses are propositions

We’ve seen how a semantic proposition isn’t always expressed in a syntactic clause. So dividing a sentence into propositions can lead to more units than dividing it into clauses. But the reverse is true too: not every clause expresses a proposition. So dividing a sentence into propositions can also lead to fewer units than dividing it into clauses. This can happen when a clause doesn’t appear to express a proposition at all. For example, consider the two clauses in (94).

(94) I think it will rain.

We could try Cristofaro’s tag question test to help identify which of the two clauses in (94) is an assertion, as in (95).

(95) I think it will rain, won’t it? (= Isn’t it true that it will rain?)

Syntactically, the sentence in (94) is a complex sentence, with “I think” as its main clause. But the tag question test in (95) shows that the subordinate clause, “it will rain,” can be taken as an assertion. Understood that way, the main clause is “transparent” to the tag question, which “sees through” it, referring to the subordinate clause.

However, the main clause in (94), “I think,” can also be seen as an assertion. This is shown by the sentence negation test in (96).

(96) It’s not true that I think it will rain. (= I don’t think that.) (≠ It won’t rain.)

Both interpretations are possible, depending on emphasis. The statement can be seen as being mainly about the likelihood that it will rain, as in (97) and (98).

(97) I think it will rain, won’t it?

(98) I think it will rain, but it might snow.

Or the statement can be seen as being mainly about the speaker’s thought, as in (99) and (100).

(99) I think it will rain, but I’m not sure.

(100) I think it will rain, don’t you?

Main clause structures like “I think” are often spoken or intended to be read without emphasis, as in (97) and (98). Used that way, they function not as an assertion, but as a formulaic expression of the speaker or writer’s attitude to an assertion made in a subordinate clause. Brinton (2008) refers to such semantically weak main clauses as “comment clauses.”

A comment clause like “I think” can be replaced, with similar effect, by an impersonal adjunct like “probably”, as in (101).

(101) I think it will rain. ≈ It will probably rain.

Other comment clauses can be similarly replaced by impersonal elements, as in (102) and (103).

(102) They say it will rain. ≈ Supposedly, it will rain. ≈ It’s supposed to rain.

(103) It seems it will rain. ≈ Apparently, it will rain.

In contrast, a main clause that makes an assertion, like “he thinks,” can’t be replaced with similar effect by an impersonal adjunct, as in (104).

(104) He thinks it will rain. ≠ It will [probably / apparently / supposedly] rain.

Brinton (2008) also refers to comment clauses as “clausal pragmatic markers.” Such grammaticalized markers can appear at various places in a sentence, as in (105)-(107).

(105) I think it will rain.

It will, I think, rain.

It will rain, I think.

(106) They say it will rain.

It will, they say, rain.

It will rain, they say.

(107) It seems it will rain.

It will, it seems, rain.

It will rain, it seems.

The semantic parsing method used in this study doesn’t treat such pragmatic markers as separate propositions.

Comment clauses aren’t the only type of syntactic clause that doesn’t always seem to express a separate proposition. Consider the highlighted portions of (108)-(110), taken from President Obama’s 2015 speech to the UN General Assembly, which is in the corpus for this study.

(108) We see an erosion of the democratic principles and human rights that are fundamental to

this institution’s mission.

(109) There are certain ideas and principles that are universal.

(110) That’s what those who shaped the United Nations 70 years ago understood.

The highlighted portions of (108)-(110) are there for narrative cohesion and emphasis, rather than semantic content. Larson (1984, 457) notes: “The greatest amount of mismatch between languages probably comes in the area of devices which signal cohesion and prominence.” Her translation method recommends first stripping away such semantically light elements from the original message, so that its syntax mirrors the semantic structure of the underlying propositions, before reformulating those propositions in the target language. Accordingly, we can restate (108)-(110) so that their syntax more closely mirrors their semantic structure, as in (111)-(113).

(111) The democratic principles and human rights that are fundamental to this institution’s

mission are eroding.

(112) Certain ideas and principles are universal.

(113) Those who shaped the United Nations 70 years ago understood that.

In cases like (108)-(110), where the main clause has a semantically light predicate, this study parses the short main clause along with the more informative subordinate clause as a single functional proposition, equivalent to (111)‑(113).

This approach is useful for cross-linguistic comparison. One problem is that it’s not always easy to decide if a short main clause which sets the framework for a more informative subordinate clause should be treated as a comment clause or as an assertion. The more semantically strong or emphatically spoken the predicate in the main clause, the more that clause can feel like an assertion in its own right. For example, consider the main clause in (114), taken from the same speech.

(114) I recognize that democracy is going to take different forms in different parts of the world.

The main clause in (114), “I recognize,” behaves differently from the comment clauses or pragmatic markers we saw above, in several respects: First, it feels more emphatic than “I think,” which can be spoken without emphasis. Second, it can’t be replaced with similar effect by an impersonal adjunct, as in (115).

(115) ≠ Democracy is probably/definitely going to take different forms in different parts of

the world.

Third, it’s harder to move “I realize” to different parts of the sentence, as in (116) or (117).

(116) ?Democracy is, I recognize, going to take different forms in different parts of the world.

(117) ??Democracy is going to take different forms in different parts of the world, I recognize.

Fourth, (114) can be restated as two independent clauses, as in (118) and unlike (119).

(118): Democracy is going to take different forms in different parts of the world, and I recognize

that.

(119): *It’s going to rain, and I think that.

The above evidence supports the feeling that (114) is both an assertion of the speaker’s recognition and an assertion about democracy. A case can be made for not attributing functionally independent status to the main clause in a sentence like (114): Verhagen (2001: 349) describes such a main clause as “conceptually dependent” on the subordinate clause, which “provides the most important information.” Still, based on evidence like (115)-(118), this study treats both the main clause and the complement clause in a sentence like (114) as functionally independent propositions, for ease of cross-linguistic comparison. We’ll come back to this in section 3 of this annex.

In contrast, the less semantically strong or emphatically spoken the predicate in the main clause, the more that clause can feel and behave like a comment clause. Consider the main clause in (120), taken from the same speech.

(120) I believe that capitalism has been the greatest creator of wealth and opportunity that the

world has ever known.

The propositional status of the main clause is harder to pin down in (120) than in (114). Is (120) just asserting that capitalism has a good side, with the main clause, “I believe,” functioning as a pragmatic marker, like unstressed “I think”? Or is the sentence also making an assertion about the speaker’s belief that that’s true? “I believe” in (120) seems to occupy a middle ground in terms of semantic strength – stronger than unstressed “I think,” but weaker than “I recognize” in (114). The case for the comment clause interpretation of (120) is strengthened by the fact that “I believe” can be moved to a different place in the sentence with similar effect, as in (121).

(121) Capitalism has, I believe, been the greatest creator of wealth and opportunity that the

world has ever known.

The comment clause interpretation of (120) is also supported by the fact that the sentence doesn’t work very well if we try to restate it as two independent clauses, as in (122).

(122) ?Capitalism has been the greatest creator of wealth and opportunity that the world has

ever known, and I believe that.

Another test, since the sentences in question are taken from a speech, is how emphatically the main clause is spoken. All the above tests give results which are on a continuum and open to subjective judgment. So the distinction between assertive force and pragmatic function for the main clause in a sentence like (120) is less than clear-cut.

In such borderline cases, this study makes a parsing decision based on tests such as those illustrated above. If the evidence favors seeing the main clause as an assertion, both main and subordinate clause are treated here as functionally independent propositions. If the evidence favors seeing the main clause as a pragmatic marker, the two clauses are parsed together as a single proposition. Whatever parsing decision is made for the original English version of a sentence, the same decision is applied as consistently as possible to all translated or interpreted versions of that sentence. This ensures that different language versions of a clause with borderline propositional status aren’t recorded as involving changes in semantic relations because of different parsing decisions applied to the original and various translated or interpreted versions of that clause.

2.3 Subordination and coordination

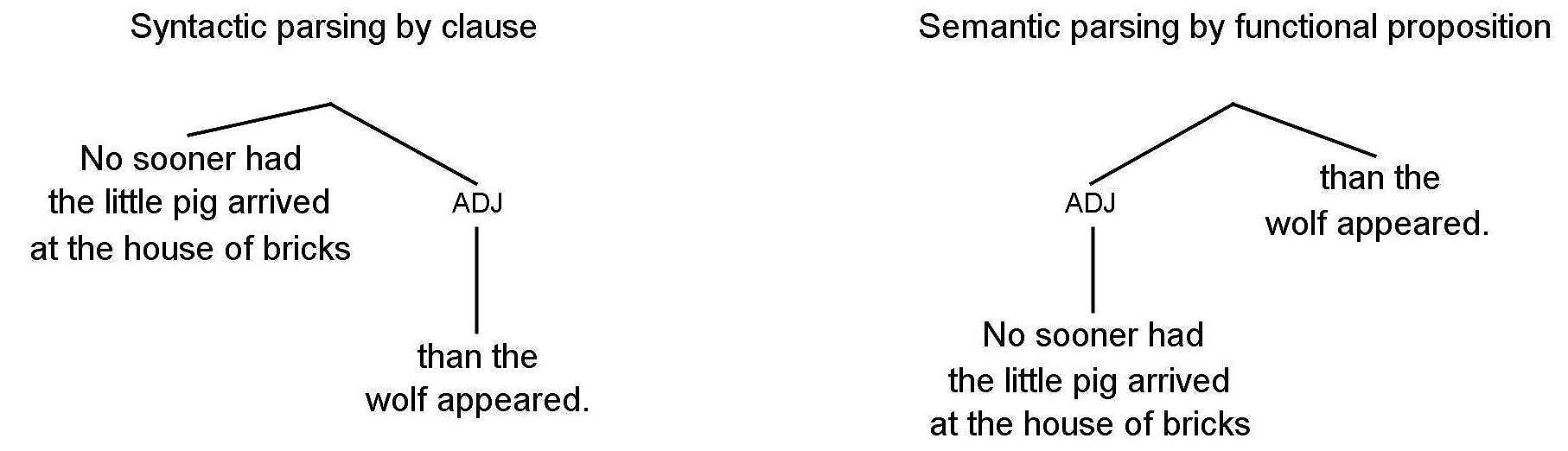

We’ve seen how syntactic relations of subordination between clauses don’t always correspond to semantic relations of subordination between propositions. In fact, the syntactic and semantic hierarchy is sometimes reversed, with a main clause providing background information and a subordinate clause making a functionally independent assertion. An example can be seen in (123).

(123) No sooner had the little pig arrived at the house of bricks than the wolf appeared.

Syntactically, the main clause in (123) is “No sooner had the little pig arrived at the house of bricks.” But the word order and tense of that clause indicate that it’s functionally subordinate to the other clause. It’s clear that the pig arriving at the house of bricks is background, assumed information and that the salient, asserted information is that the wolf appeared. The tag question test confirms this, as in (124) and (125).

(124) No sooner had the little pig arrived at the house of bricks than the wolf appeared,

didn’t he?

(125) *No sooner had the little pig arrived at the house of bricks than the wolf appeared,

hadn’t he?

Functionally, “no sooner” acts here as a subordinating link, like “as soon as” in (126).

≈ (126) As soon as the little pig arrived at the house of bricks, the wolf appeared.

Following our semantic, functional approach, the independent assertion in (123) should be treated as the main proposition, even though it’s expressed syntactically in a subordinate clause. The contrast is illustrated in figure 86.

Figure 86

Contrast between syntactic and semantic analysis of subordination

The sentence illustrated in figure 86 is a clear case of mismatch between syntactic and functional subordination, with the proposition expressed in the syntactic main clause functionally subordinate to the one expressed in the subordinate clause. But it’s not always easy to tell which of two asymmetrically linked propositions is functionally subordinate to the other, or even if their link is asymmetrical at all. Consider a sentence like (127).

(127) My wife’s learning Japanese, because she loves Japan.

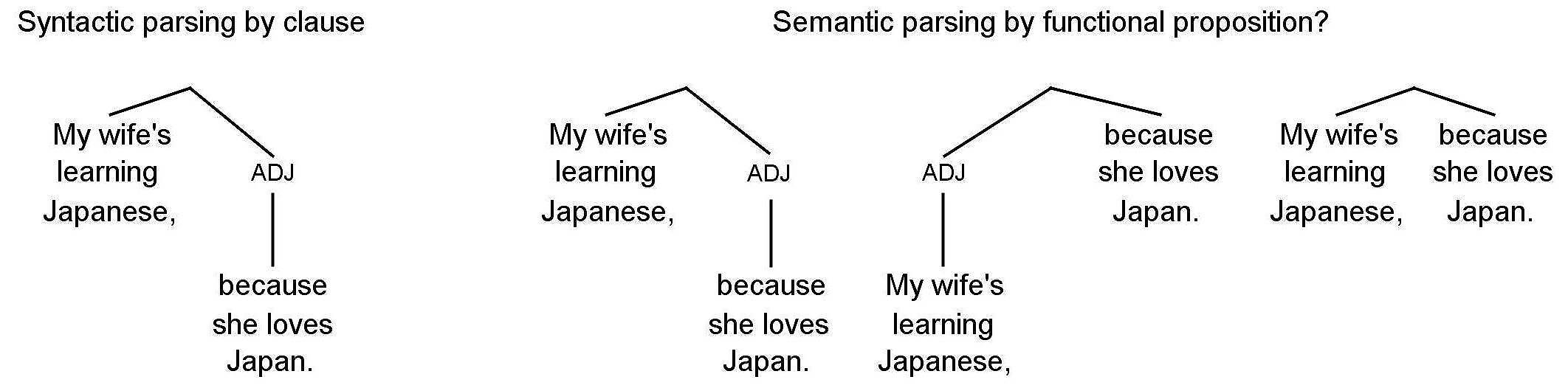

Is the link here one of functional subordination or coordination? And if it’s subordination, which proposition is subordinate to the other? Traditional grammar generally classifies “because” as a subordinating conjunction. But functionally, its subordinating function isn’t always so clear. The sentence in (127) can be seen as being as much about the speaker’s wife’s love for Japan as about the fact that she’s learning Japanese. The contrast is illustrated in figure 87.

Figure 87

Borderline relations of semantic subordination

Or we can reverse the propositions from (127), as in (128).

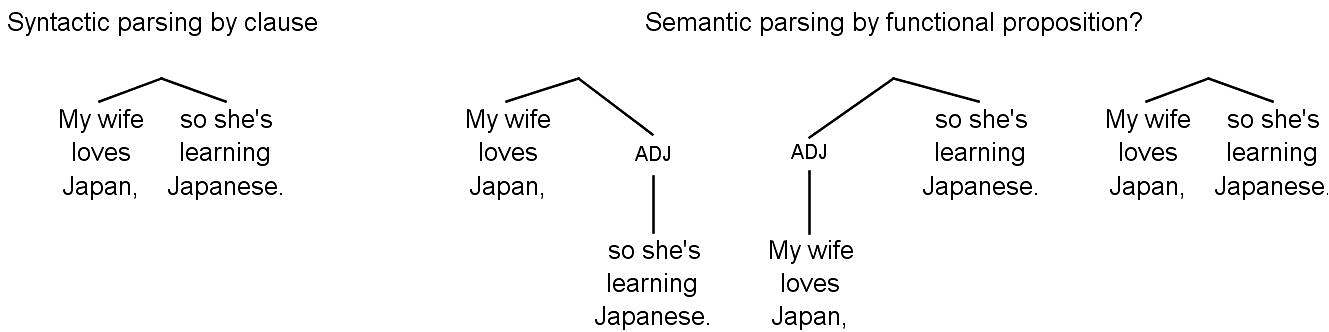

(128) My wife loves Japan, so she’s learning Japanese.

Traditional grammar generally classifies “so” as a coordinating conjunction. But, like before, this sentence may be seen as being as much about the fact that the speaker’s wife is learning Japanese as about her love for Japan. Again, the choice is unclear, as illustrated in figure 88.

Figure 88

Borderline relations of semantic subordination

This functional ambiguity is characteristic of various clause links in different languages. Cristofaro (2003: 2) cites the example in (129) from Mandarin (gloss added), with a suggested English translation.

(129) 她 喝了 酒, 就 睡著了.

Tā hēle jiǔ, jiù shuìzháole.

She drink-perf wine, then go-to-sleep-perf.

After she drank the wine, she went to sleep.

From the suggested translation, Cristofaro concludes that the functionally subordinate event in the original Mandarin sentence is the woman drinking the wine, and that the main event is her going to sleep. But the sentence could just as well be translated as in (130), (131) or (132).

(130) She drank the wine before going to sleep.

(131) She drank the wine, then went to sleep.

(132) She drank the wine and went to sleep.

In the Mandarin sentence in (129), the only overt link between the two event descriptions is the word “就 (jiù)” (≈ “then”) at the beginning of the second clause. Cristofaro’s suggested translation sees this link as subordinating the previous clause. But depending on the function attributed to the link, the main event described in the sentence can be seen as the person drinking the wine, her going to sleep, or both, as reflected in the variety of possible translations. Paul (2016: 185) sees clause links in Mandarin as “a challenge for the traditional analysis of complex sentences into a ‘subordinate’ and a ‘main’ clause.”

Culicover and Jackendoff (1997) and Yuasa and Sadock (2002) discuss clauses which appear as syntactically coordinate but are functionally subordinate – a phenomenon they refer to as “pseudo-subordination.” Ross (2016) provides a cross-linguistic analysis of this phenomenon, which he calls “pseudocoordination.” For example, the prototypical English coordinator “and” can function as a subordinator of the following clause, as in (133).

(133) Try and catch me!

(≈ Try to catch me!)

It can also function as a subordinator of the previous clause, as in (134).

(134) One wrong step and we’re done for!

(≈ If we take one wrong step, we’re done for!)

The role of “and” as functional coordinator or subordinator is harder to pigeonhole in a sentence like (135).

(135) You should lie down and have a nap.

(≈ You should lie down and you should have

a nap.)

(≈ You should lie down to have a nap.)

The same is true of the null link in juxtaposed clauses like (136).

(136) Go get your toothbrush.

(≈ Go and get your toothbrush.)

(≈ Go to get your toothbrush.)

Such covert, functionally ambiguous clause links are typical of a Sinitic language like Mandarin, as shown in (137) and (138).

(137) 我 來 幫助 您.

Wǒ lái bāngzhu nín.

I come help you.

I’ll come and help you. / I’ll come to help you.

(138) 我 有 個 哥哥, 住 在 紐約.

Wǒ yǒu ge gēge, zhù zài Niǔyuē.

I have a brother, live in New York.

I have a brother who lives in New York. / I have a brother and he lives in New York.

Transferring such sentences from a language with covert links, like Mandarin, into a language requiring overt links can force a choice as to which functional box to put those links into. Cristofaro (2003: 41) relies on translation choices to classify clause links as coordinating or subordinating, saying that we can “assume that the translation used preserves the conceptual organization” of the original. But a Mandarin speaker listening to or reading a sentence like (137) or (138) may feel no obligation to make such a binary choice. The links between the clauses can be seen as both coordinating and subordinating, or somewhere in the gray area between the two.

Again, to minimize the effect of such borderline decisions on our data, care has been taken in this study to consistently parse all language versions of a sentence the same way, whenever the information content is judged to be the same. This rule has been applied even in cases where a proposition may feel more functionally subordinate in one language version than in another, because of features like punctuation, nesting or grammatical deranking. This last issue will be discussed in section 3 of this annex.

Now we’re familiar with the semantic parsing method used in this study and how it differs from syntactic parsing, in being guided by whether clauses and other phrases are functionally independent assertions. And we’ve seen some of the problems and uncertainties that can arise in applying that method. Finally, let’s see how the focus of attention on assertions can shift as a complex sentence moves along.

← 1. Propositions

→ 3. Shifting focus