4.1.4 Changes in semantic relations

The third indicator of difficulty recorded for each translated or interpreted version of a sentence is changes in semantic relations – that is, changes in which propositions are directly attached to which other propositions and in the type of attachment. To measure this feature, we can use the same number lines as before. But now we want to show how the propositions represented by the numbers in those lines are attached to each other hierarchically. We want to show which propositions are functionally independent. And for each functionally subordinate or reported proposition, we want to show which parent proposition it’s attached to and what role it plays in relation to that parent.

So far in this section, we’ve been placing semantic parse trees below the segmented texts for various language versions of our sample sentence. Those trees have included a label at each node above a functionally subordinate or reported proposition, indicating the semantic relation of that proposition to its parent – mod (modifier), arg (argument), adj (adjunct) or rep (reported speech or thought). Now we want to compare those semantic relations in different language versions of the sentence.

To do that, we place those same relation labels over the numbers in the number line for each language version. So each number for a functionally subordinate or reported proposition gets a label indicating the relation of that proposition to its parent. We also add the number of the parent to the label. A number for a proposition which is syntactically subordinate but functionally independent doesn’t get a label. Guidelines for indicating relations between propositions on number lines are detailed in section 1.4 of annex I.

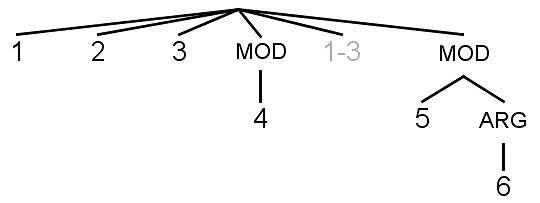

To see how this works, consider figure 38, which shows the original English version of the same sample sentence we’ve been looking at, including segmented text, semantic parse tree and number line. This time, relation labels are placed above the numbers for functionally subordinate or reported propositions in the number line. Each label indicates the semantic role of that proposition in relation to its parent(s), plus the number(s) of the parent(s).

English: [Each Party shall prepare,]1 [communicate]2 [and maintain successive]3 [nationally determined]4 [contribu-tions]1-3 [that it intends]5 [to achieve.]6

1 2 3 {4} 5 6

Figure 38

English version of sentence with relation labels

In the original English sentence in figure 38, propositions 1, 2 and 3 are functionally independent. So the numbers 1, 2 and 3 are placed at the top level of the English parse tree; and the numbers 1, 2 and 3 in the number line have no labels. Propositions 4 and 5 each modify a noun in propositions 1, 2 and 3 (their shared argument, “contributions”). So the nodes above the numbers 4 and 5 in the tree are labeled “mod” and are at the same level of the tree as the numbers 1, 2 and 3; and the numbers 4 and 5 in the number line are labeled “mod1-3.” Proposition 6 is an argument of proposition 5. So the node above the number 6 in the tree is labeled “arg” and is at the same level of the tree as the number 5; and the number 6 in the number line is labeled “arg5.”

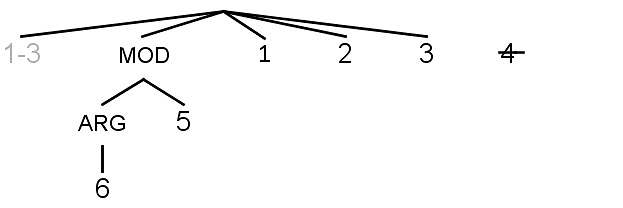

The Turkish translation of the same sentence, including Turkish text, English gloss, parse tree and number line, is shown in figure 39. Relation labels are again placed above the numbers for functionally subordinate propositions.

Turkish: [Tarafların her biri]1-3 [ulaşmayı]6 [amaçladığı]5 [ulusal katkıları hazırlar,]1 [tebliğ eder]2 [ve muhafaza eder.]3

Gloss: [Each party,]1-3 [to achieve]6 [that it intends]5 [shall prepare national contributions,]1 [communicate]2 [and maintain.]3

{6} {5} 1 2 3 4Δ

Figure 39

Turkish translation of sentence with relation labels

Most propositions in the Turkish translation of the sentence in figure 39 are hierarchically attached to each other in the same way as in the original English version in figure 38, despite the differences in their linear order. The three propositions which were functionally independent in the original English version – propositions 1, 2 and 3 – are independent in the Turkish translation too. So the numbers 1, 2 and 3 aren’t labeled in the Turkish number line in figure 39, just as they weren’t labeled in the English number line in figure 38. Propositions 5 and 6 in both English and Turkish are functionally subordinate, and are attached to the same parents and in the same way in both versions. Proposition 5 modifies a noun in propositions 1, 2 and 3. And proposition 6 is an argument of proposition 5. So the numbers 5 and 6 in the Turkish number line in figure 39 have the same relation labels as in the English number line in figure 38, even though their linear positions in the sentence are different.

There’s one difference in semantic relations, as recorded here, between the English and Turkish versions of the sentence in figures 38 and 39. The original English version of proposition 4 in figure 38 says “nationally determined,” consisting of a predicate and an adjunct. So it’s segmented as a separate proposition in that version. The Turkish translation in figure 39 says “national” – just a modifier with no arguments or adjuncts. As explained in annex I, the semantic parsing method used in this study doesn’t segment a modifier with no arguments or adjuncts as a separate proposition. So there’s no proposition in the Turkish translation of our sentence in figure 39 corresponding to proposition 4 in the original English version in figure 38. Our method records that as a change in semantic relations.

If there was a proposition in the Turkish translation corresponding to proposition 4 in the original English version, but with a different type of attachment or a different parent, the number 4 would be included in the Turkish number line in figure 39 and marked accordingly with a relation label. That label would be different from the label over the number 4 in the English number line. So the number 4 in the Turkish number line would be followed by a “Δ” (“delta” for “change”). As it is, there’s no proposition in the Turkish translation corresponding to proposition 4 in the original English version. So the number 4 is removed from the sequence of numbers representing propositions in the Turkish number line in figure 39. Instead it’s moved to the end of the line, in gray – to indicate that what was proposition 4 in the English version is missing as a separate proposition in the Turkish version. And it’s followed by a “Δ,” to mark that as a change in semantic relations.

Again, that doesn’t mean the Turkish translation of the sentence in figure 39 is wrong. When a proposition in a translated or interpreted version of a sentence is marked here as a change in semantic relations, that means it isn’t attached to the same parent and in the same way as in the original English version, with no value judgement as to the appropriateness of that change. And omitting the central part of a proposition (its predicate), as in the Turkish translation of our sample sentence, makes the semantic relations in that version different from the semantic relations in the original English version in that respect.

Such a change in semantic relations can lead to a greater or lesser change in meaning. The Turkish translation in figure 39 may have a slightly different meaning compared to the original English version. The phrase “national contributions” in the Turkish translation may suggest that contributions are just made by countries, rather than that they’re determined by countries, as in the English version. In other cases, a change in semantic relations can lead to a much greater change in meaning.

The total number of changes in semantic relations in each translated or interpreted version of a sentence compared to the original English version is entered in the data table on the display page for that sentence, in the row for the language in question, under Semantic changes. There’s one “Δ” in the number line for the Turkish translation of our sentence in figure 39. So we’ll enter “1” for the number of semantic changes in the Turkish translation of that sentence.

Table 5

Sample data table showing count for changes in semantic relations in Turkish translation of sentence

| Mode | Text / Speech | Sentence number | Subordinations | ||

| Legal translation | Paris Agreement | 29 | 3 | ||

Target language | Reordering Σi=1 Σj=i+1 I(xj<xi) | ± Nestings { } {{ }} {{{ }}} | Semantic changes Δ |

||

| Russian | |||||

| Hungarian | |||||

| Turkish | 1 | ||||

| Mandarin | |||||

| Japanese | 12 | 2 | 1 | — | |

← 4.1.3 Nesting changes

→ 4.1.5 Completed display