3. Indicators of difficulty in translation or interpretation

This study identifies three features of translation or interpretation as indicators of difficulty – reordering, nesting changes and changes in semantic relations. Each of those features involves the linear or hierarchical relations between propositions. A proposition refers here to the set of logical relations among entities in an event or situation established by a logical function – a predicate.

One dimension in which relations between propositions can change is horizontal: with changes in their linear order or in structures where one proposition is nested inside another. The other dimension in which those relations can change is vertical: with hierarchical changes in the way a subordinate proposition is attached to its parent or which proposition that parent is.

3.1 Reordering

“Reordering” in this study means reordering of propositions: a translator or interpreter’s need or choice to move a proposition from where it was in the original version of a sentence to an earlier or later place in translation or interpretation, in relation to the other propositions.

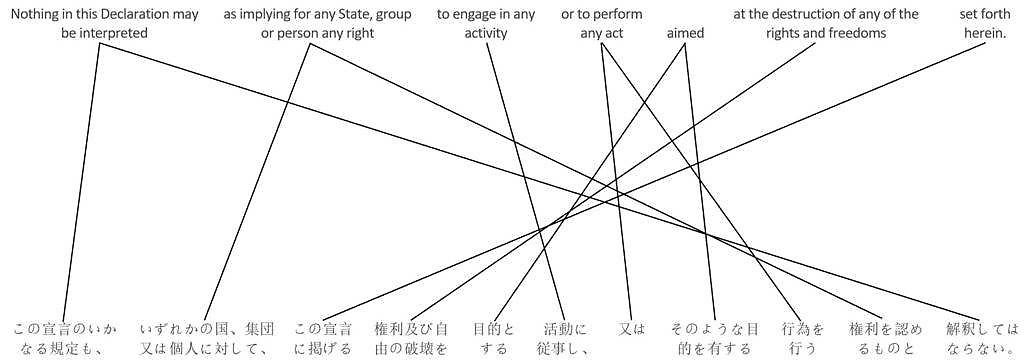

Suppose a Japanese translator is translating the Universal Declaration of Human Rights from English into Japanese. Structural or stylistic differences between the two languages may lead them to change the order of propositions in a sentence, as illustrated in Figure 1. (Lines connect corresponding propositions in each version of the sentence. Several English propositions are split apart in Japanese.)

Figure 1

Universal Declaration of Human Rights, last sentence, English and Japanese versions

To produce a result like the Japanese translation in Figure 1, the translator would have to read through the entire English version of the sentence, understanding its seven propositions and the relations between them, before deciding which part of which one to translate first. After translating each part, they’d have to re-examine the remaining parts of the English version and the relations between them, before deciding which one to translate next. In contrast, a translator working into a language with similar complex sentence structure to English could begin translating the sentence as soon as they’d read the first proposition, then go on to the next one and so on, without having to recall or reread the rest of the sentence each time.

The problem can be even greater in simultaneous interpretation. An interpreter hearing the English version of the sentence in Figure 1 without a written copy would be unlikely to produce such a nicely reordered result as the cited Japanese translation in real time, because of the great burden that could place on their working memory. To do so, they’d have to wait till they’d heard the end of the English version, retaining seven different propositions and the relations between them, before deciding which part of which one to interpret first. After interpreting each part, they couldn’t reread the sentence like a translator could. So they’d have to try to recall the remaining parts of the sentence and the relations between them before deciding which one to interpret next. To achieve a more manageable cognitive burden, they’d probably produce a result with less reordering, less nesting and therefore less structural accuracy. The more parts of a complex sentence an interpreter tries to retain and juggle around, the more difficult their task becomes.

Several studies have shown reverse recall of verbal information to be more difficult than forward recall. Donolato, Giofrè and Mammarella’s (2017) review of literature on the subject concludes: “In verbal span tasks, performance is worse when recalling things in backward sequence rather than the original forward sequence.” Similarly, experiments by Anders and Lillyquist (2013) and by Thomas, Milner and Haberlandt (2003) find reverse recall of information to be much slower than forward recall. Not to mention the difficulty of recalling reordered bits of split propositions.

The more the order of propositions changes from source to target language in translation or interpretation, the more the task of recalling them approaches reverse recall and, according to the above findings, the more difficult that task becomes. Schaeffer and Carl (2014) propose parallel word order as a criterion for “literal translation,” which they find to be associated with less cognitive load than “non‑literal” solutions in English-to-Spanish translation. Birch et al. (2008) find reordering to be a strong predictor of translation “difficulty” as reflected in the performance of statistical machine translation engines.

In studies of translation from English into Danish, German and Spanish, Bangalore et al. (2015; 2016) find differently ordered syntax to be associated with higher cognitive load. Vanroy (2021) reports studies finding reordering of word groups to be associated with greater production difficulty in English-to-Dutch translation. He also proposes a tool for predicting the translation difficulty of a sentence based on various features of the language pair of translation, including the need for reordering.

3.2 Nesting changes

A “nesting” in this study means a structure where one proposition is syntactically surrounded by the predicate and arguments of another proposition. An example of a nesting in English is the sentence “The cat the dog was chasing ran up the tree.”

In a language with typically left-branching structure, like Japanese or Turkish, a clause or other phrase expressing a proposition generally has its subject near the beginning and its predicate in final position. So a complex sentence in a language like that can have more nestings than a comparable sentence in a language with typically right-branching structure, like a European one. This tendency towards nesting in a left-branching language can be particularly strong in formal speaking and even more in formal writing, where long, complex sentences can be common.

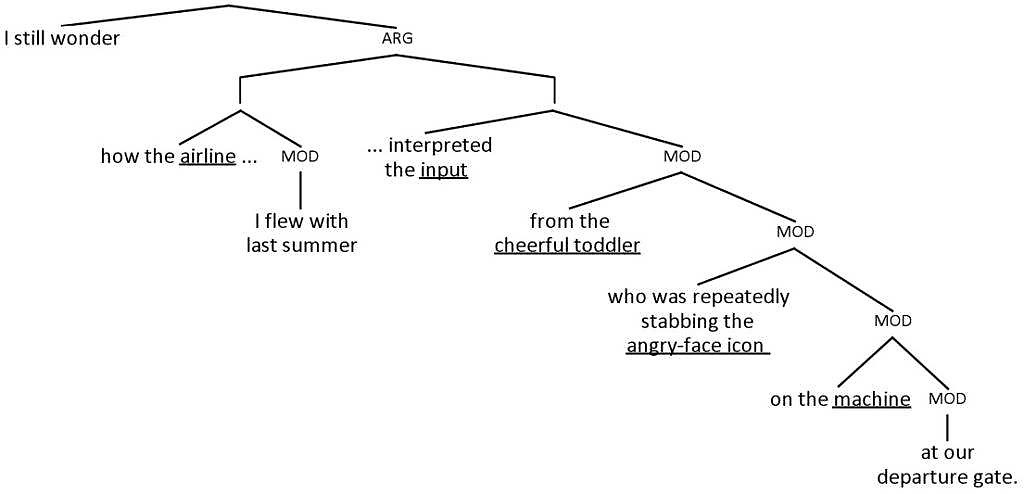

The higher nesting rate that can characterize formal writing in a left‑branching language, or in a language with mixed branching structure, may be compounded in translation from a right-branching language. For example, Figure 2 shows a parse tree of the propositions in an English sentence from a 2016 article by A. Hill in the Financial Times.

Original English version of sentence

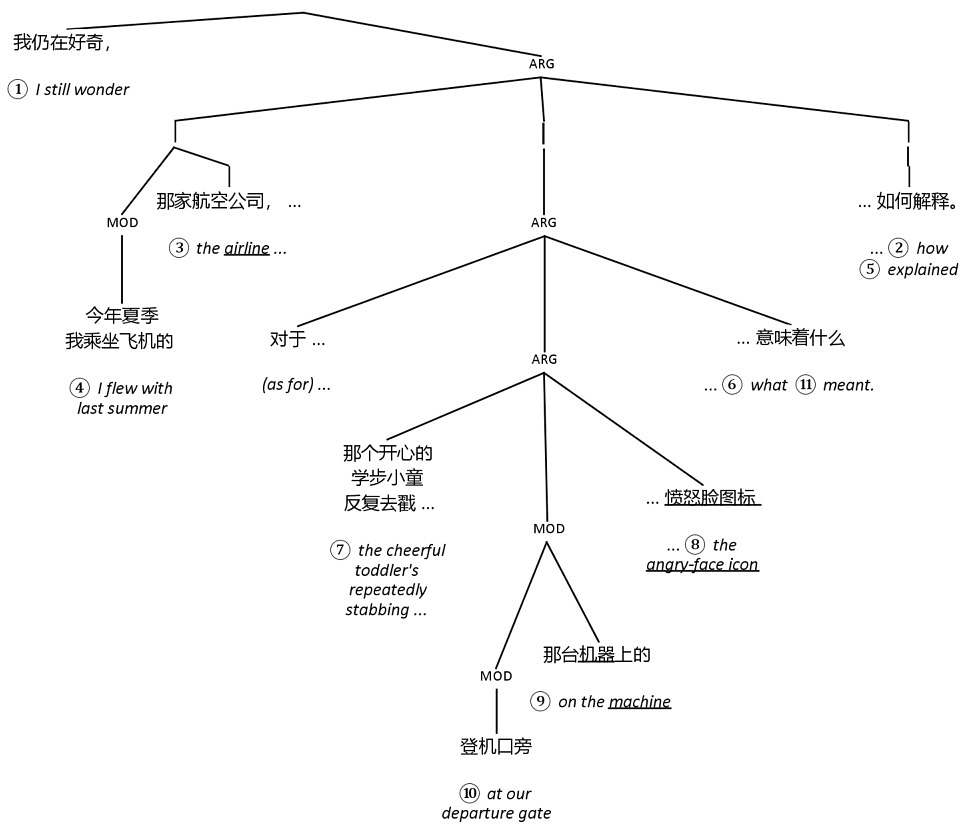

But the same sentence from the article as it appeared in Mandarin translation in the Financial Times Chinese has several syntactically split propositions, with parts which stay unresolved over long distances, as illustrated in Figure 3. The numbers show the order the branches need to be read in to make sense in English.

Figure 3

Mandarin translation of sentence

The original English version of the sentence in Figure 2 is easy enough to process. But the Mandarin translation in Figure 3, though structurally accurate, is much harder to process, because of the multiple nestings. Mandarin translations of foreign publications can be full of this sort of unwieldy structure. This may be because the translators are careful to preserve the structure of the original text. If they’re translating an official text, they may feel under even more pressure to be precise. And they – or their supervisors or editors – may be unaware of or unconcerned by the trade-off between structural accuracy and processing difficulty illustrated in this example.

Hawkins (2014) posits a number of universal efficiency principles of the human language faculty, including a preference for minimal phrasal combination domains (PCDs). A PCD is defined as the smallest linear string required by the human syntax processor to link a phrase head to a directly subordinate constituent. A universal tendency towards minimal PCDs is reflected in studies of grammaticalized phrase order preferences across languages, including studies by Greenberg (1963) and Dryer (1992). This tendency has been confirmed in corpus research and several tests of subjective phrase order preferences. Those tests have involved right-branching languages like English (Hawkins 2000), left-branching languages like Japanese and Korean (Hawkins 1994; Yamashita and Chang 2001, 2006; Choi 2007) and languages with mixed branching direction like Cantonese (Matthews and Yeung 2001). In all languages and for all phrase types tested, the evidence indicates that “processing becomes harder, the more items are held and operated on simultaneously when reaching any one parsing decision,” and that “processing complexity and difficulty increase as the size and complexity of the different processing domains increase” (Hawkins 2014: 47).

Karlsson’s (2006: 2) study on center-embedding (nested clauses) in various languages finds that “multiple clausal center-embedding is not a central design feature of language in use” and that “the maximal degree of center-embedding in written language is three.” Quirk et al. (1989: 1040) consider even doubly nested clauses to be ungrammatical and “completely baffling.” Karlsson’s study involves European languages, but he suggests that “it nevertheless seems reasonable to assume a more general validity.” In his view, constraints on nested clauses “have their ultimate basis in the material language-processing resources and limitations of the human organism […] especially short-term memory limitations.”

As we’ve seen, the number and degree of nested propositions in a sentence is a factor of processing difficulty. But creating or eliminating a nested structure in translation or interpretation is a factor of production difficulty as well. If the original version of a sentence has a non-nested proposition and the corresponding proposition in translation or interpretation is placed in a nested structure, the transformation involves splitting the surrounding proposition. On the other hand, if the original version of a sentence has a nested proposition, the translator or interpreter can do one of two things. They can copy the elements of the nested proposition and its parent in the same order into the other language. Or they can repackage the information in such a way that one proposition no longer splits the other. Eliminating a nesting in that way, like creating a nesting, is likely to involve extra mental effort, as both transformations involve reordering the predicate and arguments of the parent proposition.

3.3 Changes in semantic relations

A “semantic relation” in this study means the place and type of attachment of a subordinate proposition – in other words, which parent it’s directly attached to and its semantic role in relation to that parent. For example, consider the sentence “Answer the questions on the board.” Pragmatic knowledge suggests that the phrase “on the board” is meant to be taken as a modifier of the noun “questions.” But that phrase might instead be translated or interpreted in another language as an adjunct to the predicate “answer.” So the translated or interpreted sentence would end up meaning “Answer the questions (and write your answers) on the board.”

A translated or interpreted version of a complex sentence which changes the hierarchical relations between propositions in the original version isn’t necessarily wrong. It just means that the propositions in question aren’t attached in the same places and in the same ways in both versions of the sentence. The fact that a translator or interpreter made such a change suggests that they were for some reason unable to reproduce or uncomfortable reproducing the original semantic relations. Whatever the reason, the fact that such a change was made is taken here as an indication that the translator or interpreter encountered some sort of difficulty that led them to do so, rather than reproducing the hierarchical structure of the original.

Taking reordering and nesting changes as indicators of difficulty is justified by empirical evidence, as we’ve seen. The case for taking changes in semantic relations as an indicator of difficulty is more pragmatic. When a group of propositions attached in one way in the original version of a sentence is isolated and contrasted with the same propositions attached in a different way in translation or interpretation, it’s generally clear that the meaning is different in that respect.

When dealing with a short sentence, a good translator or interpreter would be unlikely to make such an obvious mistake as the example given above about writing answers on the board. But in long, complex sentences such as those characteristic of legal texts, especially if the translator or interpreter isn’t familiar with the details or the larger context, alternative readings of the relations between propositions can be common. And failure to reproduce those relations as intended can have major consequences.

Experiments reported by Vanroy (2021) find a significant association between changes in dependency relations among syntactic constituents and translation difficulty. The author discusses various ways of measuring the syntactic equivalence of a source and target text, which he sees as consisting in a combination of reordering, changes in dependency roles and changes in dependency relations. He concludes that such changes make the translation process more difficult.

Larson’s (1984) guide to translation technique uses the same unit of analysis as this study – the semantic proposition. She sees reproduction of the semantic relations within and between propositions, regardless of syntactic form, as key to the preservation of meaning in a successful translation. Accordingly, a change in semantic relations in translation or interpretation can be taken as a sign that the translator or interpreter has encountered some sort of difficulty that has prevented them from reproducing the original relations among propositions in the target language.