4.1.1 Sentence and data display

This study analyzes 1,136 sentences in three modes of language transfer – legal translation, subtitle translation and simultaneous interpretation. For each sentence, the semantic structure of the original English version is compared to that of its translation or interpretation into five languages from different families – Russian, Hungarian, Turkish, Mandarin and Japanese.

The analysis is carried out on a series of cross-linguistic sentence display pages, which can be found in annex II. The pages are grouped by mode of transfer and by text, talk or speech. Each display page is arranged to show the propositional structure of the original English version of a sentence and its five translated or interpreted versions. The pages count and record data on three independent variables – mode, sentence complexity and target language. The display pages also count and record data on three dependent variables, which are the three identified indicators of difficulty – reordering, nesting changes and changes in semantic relations. Each sentence and its data are displayed on a separate page, which is laid out as follows:

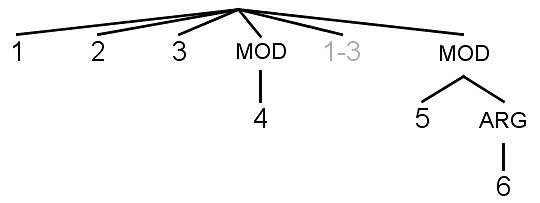

For each sentence, all six language versions are displayed on one page, in two rows. The original English version is segmented into the syntactic expressions of semantic propositions, using the parsing method summarized in section 3.1 and detailed in annex I. Each segment corresponding to a proposition is enclosed in brackets. Each proposition gets a number, which is placed after the closing bracket for that proposition. A proposition syntactically split by another proposition is shown in two separate bracketed parts. The central logical function of a proposition is the predicate. So in a split proposition, the bracketed part with the predicate is considered to be the main part of that proposition. When a proposition is split, that main part gets a normal black number. The syntactically isolated part gets the same number in gray. The original English version of a sentence from the Paris Agreement on climate change, segmented into propositions with brackets and numbers, is shown in figure 31.

English: [Each Party shall prepare,]1 [communicate]2 [and maintain successive]3 [nationally determined]4 [contribu-tions]1-3 [that it intends]5 [to achieve.]6

Figure 31

English version of sentence

Let’s take a closer look at the sentence in figure 31, to see how our parsing method is applied. If an element in a sentence is shared by more than one proposition, and if it’s contiguous with another part of one of those propositions, it’s included in the segment for that proposition and taken as implied in the segment(s) for the other proposition(s). In the sentence in figure 31, propositions 1, 2 and 3 share an initial argument – “Each Party.” That shared argument is contiguous with another part of proposition 1 – its predicate, “shall prepare.” So “Each Party” is included in the segment for proposition 1 and taken as implied at the beginning of propositions 2 and 3.

An overt coordinating link between propositions is included in the segment for the proposition that follows it. In the sentence in figure 31, segment 3 includes the initial coordinating link “and.” An overt subordinating link between propositions is included in the segment for the subordinate proposition. So segment 6 includes the initial subordinating link “to.”

As explained in annex I, a modifier is treated as the predicate of a separate proposition if it has any arguments or adjuncts of its own. In the sentence in figure 31, “determined” modifies “contributions” and has an adjunct of its own, “nationally.” So “nationally determined” is segmented separately, as proposition 4.

Besides their initial shared argument – “Each Party” – propositions 1, 2 and 3 also share a final argument – “contributions.” Proposition 4 syntactically splits the main parts of propositions 1, 2 and 3 (the parts with their predicates) from that final shared argument. That final argument isn’t contiguous with another part of proposition 1, 2 or 3, but is syntactically isolated. So it’s bracketed separately and given gray numbers (1-3), indicating the three propositions it’s part of. Gray numbers are disregarded in counting values for reordering, but the bracketed word groups they mark are important, since they affect the count for nesting changes, as we’ll see below.

A modifier without any arguments or adjuncts of its own isn’t segmented as a separate proposition. Instead, it’s included in the proposition with the element it modifies. In the sentence in figure 31, the final shared argument of propositions 1, 2 and 3 – “contributions” – has a first modifier – “successive.” That modifier has no arguments or adjuncts of its own. So “successive” is included in propositions 1, 2 and 3, along with the element it modifies – “contributions.” Unlike “contributions,” which is syntactically isolated, “successive” is contiguous with another part of proposition 3 – its predicate, “maintain.” So “successive” is included in the segment for proposition 3 and taken as implied in propositions 1 and 2.

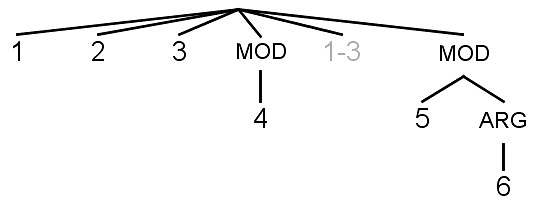

We’ve segmented the original English version of our sentence into numbered propositions. Now we want to illustrate the linear arrangement of those propositions and the hierarchical relations between them. To do that, we can place a semantic parse tree below the segmented sentence, as shown in figure 32.

English: [Each Party shall prepare,]1 [communicate]2 [and maintain successive]3 [nationally determined]4 [contribu-tions]1-3 [that it intends]5 [to achieve.]6

Figure 32

English version of sentence

with semantic parse tree

The semantic parse tree in figure 32 is structured in the same way as the trees we saw earlier in section 3.1. The difference in figure 32 is that, for clarity, each leaf on the tree has the number rather than the text of the corresponding proposition in the segmented sentence above it. The numbers on the tree appear in the same order as in the segmented sentence.

A syntactically split proposition is shown on two separate leaves of the tree. Each of those leaves has the same number – a normal black number for the main part with the predicate and a gray number or numbers for the isolated part. In the sentence in figure 32, propositions 1, 2 and 3 are split. So they’re each shown on two separate leaves of the tree. For each of those split propositions, there’s one leaf of the tree with a normal black number, corresponding to the main part of the proposition. And there’s a shared leaf with the numbers 1-3 in gray, corresponding to the shared final argument of propositions 1, 2 and 3, which is syntactically isolated from the rest of those propositions.

As explained in annex I, functionally independent propositions – propositions which make independent assertions – are placed at the top level of the tree, with no labels above them. Each functionally subordinate or reported proposition has a label on the node above it, on the same level as its parent. That label indicates the semantic relation of the proposition in question to its parent – arg (argument), mod (modifier), adj (adjunct) or rep (reported). In the sentence in figure 74, propositions 1, 2 and 3 are functionally independent. Proposition 4 modifies a shared noun in propositions 1, 2 and 3. Proposition 5 modifies the same noun, so it’s also shown as modifying an element in propositions 1, 2 and 3. And proposition 6 is an argument of the predicate in proposition 5.

To display and count values for variables, we can also place a number line below the parse tree, as shown in figure 33. The number line has a number corresponding to each proposition in the sentence. For ease of comparison between language versions, only black numbers (corresponding to whole propositions or the main parts of split propositions) are copied from the segmented sentence and the parse tree onto the number line.

English: [Each Party shall prepare,]1 [communicate]2 [and maintain successive]3 [nationally determined]4 [contribu-tions]1-3 [that it intends]5 [to achieve.]6

1 2 3 4 5 6

Figure 33

English version of sentence

with parse tree and number line

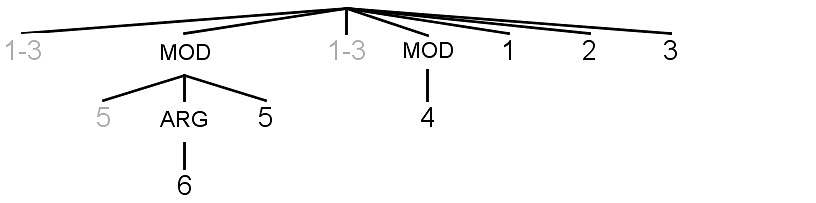

Now we want to segment and number each of the five translated or interpreted versions of our sentence, placing a parse tree and a number line below the segmented text for those versions, just as we’ve done for the original English version. To keep track of corresponding language versions of each proposition, the propositions keep the same numbers in each translated or interpreted version of the sentence as in the original English version. The Japanese translation of the sentence we’ve just been looking at from the Paris Agreement – including Japanese text, English gloss, parse tree and number line – can be seen in figure 34. The segmented sentence shows the division and order of propositions in Japanese, but with the same numbers as the corresponding propositions in English. Again, for split propositions, only the normal black numbers for the main parts with the predicates are copied onto the number line. The syntactically isolated parts have gray numbers in the segmented sentence and on the parse tree. Those gray numbers aren’t copied onto the number line.

Japanese: [各締約国は、]1-3 [自国が]5 [達成する]6 [意図を有する]5 [累次の]1-3 [国が決定する]4 [貢献を作成し、]1 [通報し、]2 [及び維持する。]3

Gloss: [Each party,]1-3 [it]5 [to achieve]6 [that … intends]5 [successive]1-3 [nationally determined]4 [shall prepare con-tributions,]1 [communicate]2 [and maintain.]3

6 5 4 1 2 3

Figure 34

Japanese translation of sentence

from Paris Agreement

In the Japanese translation of the sentence in figure 34, propositions 1, 2 and 3 are each syntactically split (by propositions 6, 5 and 4) into three parts. Proposition 5 is itself split (by proposition 6) into two parts. Propositions 1, 2 and 3 in the Japanese translation are functionally independent, just as they were in the original English version. So the numbers 1, 2 and 3 are at the top of the Japanese parse tree in figure 34, just as they were for the English tree in figure 33. Propositions 4, 5 and 6 in the Japanese translation are functionally subordinate, just as they were in the original English version. And they’re attached to the same parents, with the same semantic roles in relation to those parents, as in English. So the nodes above the numbers 4, 5 and 6 in the Japanese parse tree in figure 34 have the same labels as the nodes above those numbers in the English tree in figure 33. The propositions appear in a different linear order and are syntactically split in different ways in the English and Japanese versions of the sentence. But the semantic parse trees in figures 33 and 34 show that the hierarchical relations between those propositions are the same in both language versions.

At the bottom of the display page for each sentence is a table recording the data for that sentence. The top rows of the table record the mode, the title of the text or speech, the sentence number and (as a measure of complexity) the number of functionally subordinate or reported propositions in the original English version of the sentence. Our sample sentence is sentence number 29 from the Paris Agreement, which is a legal text. So we enter “Legal translation,” “Paris Agreement” and “29” in the corresponding boxes along the top row of the table. As we can see from the parse tree in figure 33, the original English version of the sentence has 6 propositions. Three of those propositions – numbers 4, 5 and 6 – are functionally subordinate or reported. So we enter “3” for the number of functionally subordinate or reported propositions in the upper right corner of the table.

Table 2

Sample data table showing entries for mode, text/speech, sentence number and sentence complexity

| Mode | Text / Speech | Sentence number | Subordinations | ||

| Legal translation | Paris Agreement | 29 | 3 | ||

Target language | Reordering Σi=1 Σj=i+1 I(xj<xi) | ± Nestings { } {{ }} {{{ }}} | Semantic changes Δ |

||

| Russian | |||||

| Hungarian | |||||

| Turkish | |||||

| Mandarin | |||||

| Japanese | |||||

The remaining part of the data table records counts for our three indicators of difficulty – reordering, nesting changes and changes in semantic relations – for each translated or interpreted version of the sentence. Next we’ll see how those three indicators are counted.

← 4.1 Collecting data

→ 4.1.2 Reordering