3.3.2 Reordering

“Reordering” in this study means reordering of propositions: a translator or interpreter’s need or choice to move a proposition from where it was in the original version of a sentence to an earlier or later place in translation or interpretation, in relation to the other propositions. For example, two propositions may appear in the order shown in (7) in the original version of a sentence.

(7) Please switch off all the lights before you leave the room.

But the syntax of the language a translator or interpreter is working into may lead them to switch the order of those two propositions to the order shown in (8).

(8) Before you leave the room, please switch off all the lights.

The need or choice to change the linear order of propositions like this, especially with many propositions criss-crossing over long distances, is taken in this study as an indicator of difficulty. Here’s why:

A translator translating a long, complex sentence between languages with very different structure may have to look back and forth between various parts of the original version, keeping in mind the overall structure of the unfolding sentence, so they can reproduce the relations between propositions appropriately. In contrast, a translator working between languages with similar structure, like two European languages, can generally shift their focus of attention progressively from one proposition to the next, without having to skip around or worry about reproducing relations between propositions in a different order.

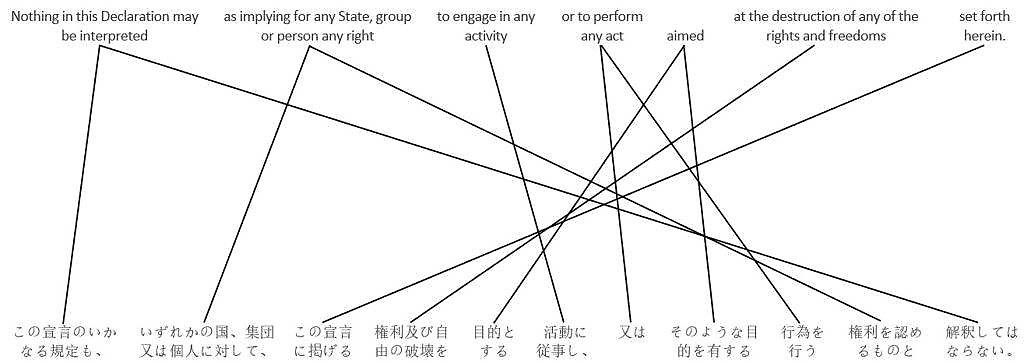

Suppose a Japanese translator is translating the Universal Declaration of Human Rights from English into Japanese. Structural or stylistic differences between the two languages may lead them to change the order of propositions between the original and the translated version of a given sentence, as illustrated in Figure 9. (Lines connect corresponding propositions in each version of the sentence. Several English propositions are split apart in Japanese.)

Figure 9

Universal Declaration of Human Rights, last sentence, English and Japanese versions

To produce a result like the Japanese translation in figure 9, the translator would have to read through the entire English version of the sentence, understanding its seven propositions and the relations between them, before deciding which part of which one to translate first. After translating each part, they’d have to re-examine the remaining parts of the English version and the relations between them, before deciding which one to translate next. In contrast, a translator working into a language with similar complex sentence structure to English could begin translating the sentence as soon as they’d read the first proposition, then go on to the next one and so on, without having to recall or reread the rest of the sentence each time.

The problem can be even greater in simultaneous interpretation. An interpreter hearing the English version of the sentence in figure 9 without a written copy would be unlikely to produce such a nicely reordered result as the cited Japanese translation in real time, because of the great burden that could place on their working memory. To do so, they’d have to wait till they’d heard the end of the English version, retaining seven different propositions and the relations between them, before deciding which part of which one to interpret first. After interpreting each part, they couldn’t reread the sentence like a translator could. So they’d have to try to recall the remaining parts of the sentence and the relations between them before deciding which one to interpret next. To achieve a more manageable cognitive burden, they’d be liable to produce a result with less reordering, less nesting and therefore less structural accuracy. The more parts of a complex sentence an interpreter tries to retain and juggle around, the more difficult their task becomes.

Miller (1956) and others have found that a person can only retain a certain number of information chunks at a time in working memory. That suggests that an interpreter’s ability to correctly recall the propositions in a complex sentence depends on: (a) their ability to organize each proposition into a conceptual chunk, (b) the number of such chunks in the sentence and (c) the order in which those chunks need to be recalled. To the extent that they managed to organize each of the propositions in a sentence like the one in figure 9 into a conceptual chunk, they might just about be able to recall them all. But then they’d be retaining each proposition as a chunk, rather than retaining the details of each one. Going for the big picture might well mean losing some of the detail. And an interpreter needs to reproduce both: the big picture as well as the detail.

What about the order of recall? What if an interpreter does more or less manage to chunk a complex sentence into propositions and retain their content, but then has to recall that content in a different order, to reproduce it in another language? In the sentence in figure 9, part of the first proposition in the English version is at the end of the Japanese version, part of the second proposition in the English version is right before the end of the Japanese version, and so on. The more the order of propositions in a translated or interpreted version of a sentence differs from their order in the original version, the more the task of recalling them approaches recalling them in entirely reverse order. Recalling verbal information in reverse order has been shown to be much more difficult than recalling it in the order it was heard in (Donolato, Giofrè and Mammarella 2017). Not to mention the difficulty of recalling reordered pieces of split propositions.

In sum, the degree to which propositions are reordered from the original version to the translated or interpreted version of a sentence is an indicator of difficulty for the translator or interpreter. This is the first indicator of difficulty measured in this study.

← 3.3.1 Structural difference

→ 3.3.3 Nesting changes